Think of the 1980s and many symbolic images come to mind: leg warmers, neon lighting, and big hair – all of them representative of the decade. It was a time when pop culture began to become more identifiable in media like television and movies, from Miami Vice to The Terminator. MTV mixed music and film together like never before, bringing new audiences to genres like sci-fi and martial arts. Action fans can easily add another example to that list, one that practically defined the movies of the era: ninjas.

Think of the 1980s and many symbolic images come to mind: leg warmers, neon lighting, and big hair – all of them representative of the decade. It was a time when pop culture began to become more identifiable in media like television and movies, from Miami Vice to The Terminator. MTV mixed music and film together like never before, bringing new audiences to genres like sci-fi and martial arts. Action fans can easily add another example to that list, one that practically defined the movies of the era: ninjas.

During the ‘80s, it seemed you couldn’t throw a shuriken without hitting a ninja. They were everywhere, and uncommon to the stealthy assassin type’s modus operandi, they were in plain sight. People were obsessed with everything related to Japan’s famous warriors, and this included video games, which was rife with them. Even game characters that had nothing ninja-like about them were often categorized as such, and America was beset by rampant ninja-related crimes. The popularity of ninjas soared.

Sega was at the forefront of the ninja craze, already having released several titles with the theme by the time the Master System was waning in America. Shinobi was a major hit for the publisher, and it followed in the wake of earlier titles like Sega Ninja in the arcade (reworked and released as The Ninja on the Master System). Chronicling the adventures of ninja Joe Musashi in his battle to save the children of world leaders (his students in the Japanese version) from the evil criminal organization Zeed, it fed players a steady diet of shurikens, multi-colored ninja foes, and one of the defining aspects of the series: Ninjutsu, or ninja magic. The game received ports on several machines, including Sega’s Master System, and that version actually introduced many gameplay aspects that were incorporated into the Genesis sequel, The Revenge of Shinobi.

Arcade Origins

The success of Shinobi in arcades made it a clear candidate for a home conversion, and while it suffered the same alterations that many home console downgrades of the time experienced, Sega also made many positive changes to way it played. Whereas the arcade original featured one-hit deaths, the Master System version included a life bar. The hostages Musashi saves now also granted him special abilities instead of just points and a shuriken power-up, like access to the bonus stage (which always appeared after each boss battle in the coin-op), additional melee and projectile weapons, and a refill of his life bar. The game straddled the line between staying true to its source material and taking advantage of the benefits of a home console. No one expected Master System owners to play Shinobi in the short and quick bursts on which arcades thrived, given that the cartridge cost significantly more than a single quarter to own, so the game had to undergo some alterations. “Arcade games you enjoy for three minutes, for 100 yen and they make you happy” explained Revenge of Shinobi director Noriyoshi Ohba in the 2015 book Mega Drive/Genesis Collected Works. “On the other hand, home console games cost 5,800 yen and have to provide gameplay for many hours without making the player bored.” It is unclear who came up with the idea for the Master System gameplay changes at Sega, but Ohba was clearly inspired by the positive changes they brought to the home console experience.

Ohba was likely very aware of how special the project was, not only for Sega but for his own career. After graduating from Waseda University in 1987, he was still unsure about where he would end up working. An economics major, his specialty in marketing and statistics limited his options in Japan’s manufacturing industry. With only toys, games, or stationary companies as his opportunities, he decided to pursue a job in gaming. He was hired as a planner at Sega, despite his lack of experience or knowledge about video games, and his first project was Wonder Boy in Monster Land, which served as his on-the-job training. Ohba learned quickly, absorbing much regarding level design, as well as designing games that contained both arcade and home console elements.

Ohba’s next project was the sequel to Shinobi, a major undertaking for someone so new to the company. He felt liberated at the prospect of working on the Mega Drive, having found the Master System hardware far too limiting. He had longed to create something that could not be done on the Famicom or other existing machines, and he wanted his next game to not only show off the potential of the new 16-bit console but to be an experience that was exclusive and enticing to prospective owners. He also wanted to emphasize the need to make the game deviate from its arcade heritage. If Mega Drive owners were to be expected to spend $50 or so on game cartridge, then it was vital that they get more for their money.

The team Ohba assembled was quite small, including only a few programmers and artists and one sound designer. As the new game’s designer, Ohba was responsible for virtually all aspects of the game’s design, from the gameplay system to the art. From the outset, he was very clear that he while he intended to maintain the essence of the original game, he wanted to capitalize on the new Mega Drive’s capabilities. “We didn’t want to simply port the arcade version of Shinobi,” he said in a 2003 interview. “We wanted to do something completely different. The reason why is that console games have their own play style, distinct from arcade games.”

It was decided very early on that the game would be set in the same universe as the first Shinobi, and that several story elements would carry over. The main character, Joe Musashi and his Oboro Clan, and the evil Zeed syndicate all returned, and the sequel was set three years after the original. Zeed would now resurface as “Neo Zeed” to exact revenge on Musashi, destroying his clan and kidnapping his bride Naoko (named after Ohba’s sister-in-law). Before dying, Musashi’s master reveals to him what happened, and the famous ninja sets out to save Naoko and destroy Neo Zeed.

Ohba was excited to be working with the series, and he knew how popular ninjas were at the time in America, which would hopefully broaden the game’s appeal. He understood that the American imagining of ninjas as almost super human and mystical beings was very different than the Japanese perception of them primarily as martial artists, and he knew that the game would likely be more popular in the U.S. than in Japan. Ohba watched many American movies as a reference, particularly Sho Kosugi ninja movies like Pray for Death and Revenge of the Ninja. Though he found the action to be unrealistic, he still regarded the films useful for helping him match the Western conceptualization of what ninjas were. According to Ohba, the desire to make ninjas more Western in style accounts for the lack of stealth gameplay in a game called Shinobi, which refers mostly to covert actions such as espionage, infiltration, and assassination. The movies he used for inspiration featured ninjas that were anything but stealthy, and that popular style of action hero fueled the character design for Revenge.

The Revenge of Shinobi’s chief designer, Naohiro Warama (also known by his pseudonym, Taro Shizuoka) shared Ohba’s vision of a realistic game that played like a Hollywood action film. Joining Sega in 1988, Warama was a self-taught artist who had been attracted to Sega because of the quality of its simulation games. He decided he wanted to work for the game-maker and made it his first stop while job hunting. Also a fan of action films, Warama fleshed out his concept of Revenge’s art style through a steady diet of the same ninja films as Ohba but with some added Hong Kong Kung fu movies and Japanese special effects programs.

Using a graphics tool made for arcade hardware and customized for the Mega Drive, he worked to create fluid animation for the game’s characters within the console’s limited memory. A new double jump had been added to Musashi’s skill set, and this required some trickery to make the motion smooth, a process he described in a 2014 interview. “For the somersault move, by using the horizontal and vertical flip functions of the hardware, we were able to create four frames of movement from only one frame. Having analyzed the movements in Kung fu films, I worked with the programmers to create the illusion of rich animation using only very few frames.”

One area where both the team devoted particular attention was to the game’s backgrounds. Ohba planned each one out completely on paper, and general images were created by the other artists. These were then converted into 16×16 pixel tiles and digitized. The team was eager to test the new Mega Drive’s power, and Ohba wanted to make sure he used every ounce of the hardware he could squeeze within his deadline. The new Shinobi game had to show off the console’s advanced features, and multi-scrolling background layers was one of its many talents. Ohba would use as many background layers as possible in every stage. Most Mega Drive games at the time used only two layers of scrolling, so he insisted that his game have three or even four.

Ohba was keen on giving players an experience that would get their adrenaline pumping but be forgiving enough to keep them coming back. The inclusion of a life bar was the perfect bridge between the quick experience arcade games offered and the replay value home titles needed to be successful. The instant death from falling into pits was maintained, but Musashi could now withstand more than a single hit, which had been the cause of much frustration for players of the original Shinobi. The life bar allowed greater freedom for trial and error, giving players the chance to see the entire game in a single session. Infinite continues perhaps provide the same benefit, but they may be seen as more disruptive of the game’s sense of immersion.

Revenge Wears a New Mask

Aside from the addition of a life bar, other changes were made to Mushashi’s gameplay. Shurikens were now finite and had to be replenished by breaking boxes scattered around each stage (though a simple code at the options screen nullifies this). The ninja stars could now be powered up by obtaining a POW icon, which made them devastatingly strong. Also, gone were the nunchuks and other melee weapons from the Master System Shinobi port. Now, Mushashi had only his katana for close-quartered combat.

Musashi’s incredible ninja magic was retained from the original Shinobi, but it was significantly upgraded for Revenge. Now, four different types were available, each with a particular function beyond simply wiping the screen of enemies, and players could select which one they wanted at any time. Karyu unleashed columns of fire dragons from below to wipe out all enemies. Mijin gave Musashi a suicide attack that devastated foes, so long as players had extra lives in reserve. Fushin magic increased the height of Muashi’s jumps, a godsend in several stages. Lastly, Ikazu created a shield that protected Musashi from several hits. The functions of these magic spells were assigned according to the necessities of a particular level, something Ohba wanted to be core to the gameplay. Activating a particular magic on a certain stage or boss can make thing significantly easier, such as using Mijin on stage 7-3’s boss, Ancient Dinosaur. On any difficulty setting except hard, the magic allows him to be dispatched with a mere three hits (hard mode requires eight). The Mijin technique actually has its origins in a previous title Ohba worked on. It was conceived as an item called “One Down Continue” that let players continue from the spot of their death. The game was canceled, but Ohba rescued the idea for The Revenge of Shinobi. Continuing from the same spot was not as common in console games as it was in the arcades, and Ohba wanted to make the option available to players, though at a price.

The level design was also factored into game’s control scheme, including the new double jump. Ohba wanted to improve the jump mechanic early on, but he wanted it to have greater meaning than simply being just another move. By designing the levels to gradually test players’ mastery of the controls, Revenge forced them to learn their layouts and which play style was best suited to advance. For instance, the game’s longest jump occurs in stage six (China Town), and the most difficult in the following stage (Wharf). Players who learned to control the double jump could brave the gap and proceed, but those who wanted another option could use ninja magic to make advancement easier. By learning when to use the Fushin technique, these areas could be passed much more easily than with the standard double jump. Ohba intended for the China Town jump to serve as training for the more difficult stage that followed, which many gamers consider to be the hardest in the whole game.

Songs from the Shadows

Perhaps the single aspect of Revenge of Shinobi that most fans remember most is its iconic soundtrack. Composed by the legendary Yuzo Koshiro, it featured themes that perfectly captured the designs and visuals of each of the game’s levels. Koshiro was a fan of the first Shinobi and wanted to create pieces that would serve as extensions of its soundtrack. He was also heavily into dance music at the time and frequented clubs that played music by groups like Soul2Soul and Maxi Priest. These were major influences on the musical style he used for Revenge. “I started listening to the latest music at the time, which was club or disco music,” he said in a 2014 interview. “I thought it’d be interesting to combine that style with the Japanese taste that Shinobi had.”

Koshiro was given free reign with the soundtrack, with Ohba’s only stipulation being that it couldn’t sound like what would be found in a traditional Japanese game. To create a fluid blend of classic East and modern West, Koshiro turned to both modern and Japanese instruments. The result was a musical score that has almost transcended the game itself and brought Koshiro into the video game spotlight. Ohba was particularly pleased with how Koshiro’s music turned out. He was so impressed with the game’s final score that he selected Koshiro for his next project, Streets of Rage a year later. As content as he was with the music, Ohba was far more demanding about the game’s sound effects. requiring Koshiro to recompose several of them to meet his specific requests.

The affinity Koshiro had for club music, which was much more popular at the time in the U.S. than in Japan, had heavily influenced his music for Revenge, and he would fine tune it even more for Streets of Rage, perhaps his most renowned work. Admittedly, the sales of the Genesis in North America also influenced his decision to use club music in both games, a move that proved not only trend-setting in his native country, but showed strong business savvy as well. He explained his decision in a 2014 interview with Red Bull Music Academy. “Club music was growing in popularity overseas at the time. It wasn’t really known in Japan then. But especially in North America, where the Mega Drive was selling, club songs were playing constantly on MTV and such. So, I knew they loved club music, so I thought if I could put this into game music, then they’d be really happy. I think that was the first time I composed music with the overseas market in mind above the Japanese market.”

Assassinating the Competition

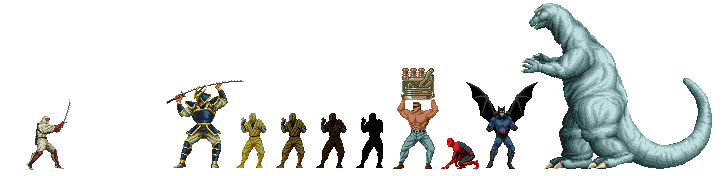

As development progressed, Ohba became more conscious of the potential hit he was making. Sega was equally aware and was intent on promoting the game and even used cross-promotion with one of its more popular licenses, Spider-Man. The Marvel hero appeared in the first two versions of the game as a boss but was removed later on when Sega’s rights to the character expired. He wasn’t the only super hero to apparently find his way into Musashi’s latest adventure. Ohba’s team was given great freedom to create the look of the game, and in some cases they went a bit too far. The Revenge of Shinobi features several “homages” to famous movie characters, including Rambo (humorously named “Rocky”), Batman, Terminator, and even Godzilla. Ohba’s original game proposal wasn’t very specific about how characters were supposed to look, describing them in simple terms like “armored samurai,” and “female ninja disguised as a nun.” Warama strove to give his designs a more original feel; however, he didn’t want to deviate too far, as that would cause the characters to lose their particular appeal. Ohba himself explained that he never intended his rough sketches to be used so literally, and he seems to cast the blame on Warama for being a bit too faithful to them. “I made some rough sketches of characters from my mind and from some photos due to my lack of drawing ability,” he told Retro Gamer magazine. “They were meant to be used as a rough example. Unfortunately, the designer of the sprites [Warama] reproduced my drawings a bit too faithfully and you know the end result. I personally think that if the designer had tried to show more of his own personality in those characters, they would have looked a lot different to the originals.” Warama’s decision to err on the side of caution caused him no small degree of embarrassment after the game’s release, when he learned that his designs actually infringed on multiple copyrights, and changes to the offending characters was ordered. Multiple revisions of the game were subsequently released as adjustments were made. In all, it took four different versions of The Revenge of Shinobi to satisfy Sega’s legal department.

Despite his own high expectations for Revenge, Ohba somehow had the impression that Sega didn’t share his enthusiasm and expected little from the Shinobi sequel. It would take a trip overseas to convince him of the opposite. To promote the game, Ohba attended both the Winter and Summer Consumer Electronics Shows (CES) in Los Angeles and Chicago to promote Revenge of Shinobi, a rarity for low level Sega employees. There, he was able to see the great impact the game made on visitors. Its animated title screen, which featured a sword-wielding ninja (reportedly modeled on martial arts legend Sonny Chiba from the Japanese television show Kage no Gundan) deflecting shurikens, and the demo levels with their impressive parallax scrolling were very popular. The media was highly impressed with the game, and it received high scores in several magazines like Game Players and Electronic Gaming Monthly.

After six months of development, The Revenge of Shinobi sliced its way onto store shelves in December of 1989. It quickly became a favorite of Genesis owners everywhere and a major reason to own the console. Interestingly, not everything the development team (now known as “Team Shinobi”) wanted to include was in the final product. According to Warama, the game’s true final boss was not supposed to be the head-banging Masked Ninja at the end of the labyrinth level. Rather, Musashi was to fight the real ninja master behind Neo Zeed, an old and bearded man in Japanese clothes. “The set-up,” Warama detailed, “was that the chief of the Shinobi village – who can be seen dying in Joe Musashi’s arms during the intro sequence – turns out to be the head of the enemy organization, Cyber Zeed.” There were two concepts about how he would reveal himself to Musashi. One had him simply revealing himself as the head of the Shinobi village, and in the other he would be a robot controlled by another villain. In addition to his martial arts skills, this final boss would also be able to summon earthquakes and falling rocks. The entire battle was sequenced and designed, but unfortunately never made it through development. The game’s short deadline caused this boss fight to be cut from the final game.

Sega did manage to incorporate the Cyber Zeed concept into its 1990 Master System release, Cyber Shinobi. In it, Musashi’s grandson fights the remnants of Zeed, now bearing the “Cyber” title. The game’s title screen lists it as “Shinobi Part 2,” a clear contradiction, given that The Revenge of Shinobi had been released a year earlier. It is possible that Ohba’s game was not viewed as a direct sequel, and he and Warama have said that Revenge was not really considered as such. It is also possible that Sega simply erred with the numbering. A similar situation occurred with Space Harrier 3-D, which took place just after the original game and was released on the Master System a year before Space Harrier II. This would not be the only liberty Sega would take with the Shinobi chronology, as it released Shadow Dancer in arcades the same year Revenge debuted on the Genesis. Despite the addition of a dog, it played much more like the first game, with similar enemies and objectives to complete. Now, there were bombs to diffuse instead of people to rescue. Shadow Dancer would eventually make its way to the Genesis in 1991 is a modified form. Neither The Revenge of Shinobi nor Shadow Dancer ever reference each other (the arcade Shadow Dancer has virtually no story at all, but the Genesis version takes place several years after Revenge) so there is some confusion as to where they fit into the overall timeline.

Other omissions include gears in the holes where Mushashi must fire shuriken to keep the ceiling from crushing Naoko in the end battle and an introductory sequence chronicling how the Oboro Clan was wiped out and how Naoko was abducted. It is interesting that a game which seemed to test the Genesis so early actually had so much content omitted not because of technical limitations but time constraints. One wonders what might have been included had more time been given to the developers.

Other omissions include gears in the holes where Mushashi must fire shuriken to keep the ceiling from crushing Naoko in the end battle and an introductory sequence chronicling how the Oboro Clan was wiped out and how Naoko was abducted. It is interesting that a game which seemed to test the Genesis so early actually had so much content omitted not because of technical limitations but time constraints. One wonders what might have been included had more time been given to the developers.

While time was a major factor preventing the team from including everything it wanted, there were indeed technical challenges. Memory issues forced a new type of bonus stage to be cut from the game. “We wanted to include bonus stages;” Ohba revealed, “however, we realized that they were not going to fit in the available memory. Unlike optical devices, which are commonly used nowadays, we were limited by the available amount of memory, as ROM was very pricey.” Whether or not the stages would have made the game better is debatable, but it would have more closely linked Revenge to the original Shinobi. Any bonus lives obtained from completing them would certainly have benefited those players who favored the Mijin technique for boss battles, to say the least.

Master of Its Craft

The Revenge of Shinobi was not only a better game than its predecessor, it illustrated that the Genesis was capable of more than just arcade ports. A true action game in every sense, it helped move Sega away from its dependence on its arcade heritage and into creating more serious original properties that were exclusive to the home console. Ohba and his team crafted a ninja epic that showed what more serious games could be like, a move preceding Sega’s focus on older gamers. The Revenge of Shinobi excels as an action game not only because it is masterfully crafted but also because it was very much in rhythm with where the genre was heading at the time. By taking advantage of all that the 16-bit hardware had to offer, it proved that gamers could look to the Genesis for arcade action right in their very home, and it helped push the console more than any other pre-Sonic title did, save for perhaps Golden Axe. This is why it has endured as a Genesis classic for so long.

After completing Revenge, Ohba’s team moved on to Streets of Rage, while Warama helped port Capcom’s arcade hit Strider to the Genesis. Later, he would move over to game programming, where he was involved with such classics as Daytona USA Deluxe and the Yakuza series. Both men still share fond memories of working on The Revenge of Shinobi. Ohba maintains that it remains his favorite project, as it was the first to give him the platform and creative freedom to make the type of game he wanted. As for Warama, he credits Joe Musashi’s second outing for helping to shape his concepts of designs and instilling within him the self-confidence to succeed in the game industry.

To Genesis gamers, The Revenge of Shinobi is a title that stands out from the rest. Many consider the third installment, Return of the Ninja Master, to be the best in the series, but it borrows heavily from its predecessor and plays like a refined and expanded version of it. Even beyond the series, the influence Revenge had on the action genre was a powerful one, particularly on the Genesis. It set a high standard that many other titles strove to reach, and its popularity has never waned, even after several further installments of questionable quality. It’s true that you can’t keep a good ninja down, and Sega fans anxiously await the next Shinobi adventure. Whenever and wherever it comes, it will always be compared to The Revenge of Shinobi.

Sources:

- Dwyer, N. (2014). Interview: Streets of Rage composer Yuzo Koshiro. Red Bull Music Academy.

- Hunt, S. (2014). The making of Revenge of Shinobi. Retro Gamer, 1(76), 82-85. Print.

- Sega of Japan. (2003). Revenge of Shinobi: Developer interview with director/designer Noriyoshi Ohba. Shmuplations.

- Strangman, R. (2002). The OPCFG interview with Yuzo Koshiro. OPCFG.

- Stuart, K. (2015). Interview with Naohiro Warama: Visual Designer. Mega Drive/Genesis Collected Works, 298-299.

- —. An interview with Noriyoshi Ohba: Sega’s prolific director on shaping the Mega Drive revolution. Mega Drive/Genesis Collected Works, 280-281.