Role playing games have been popular for years. Myst for the PC, The Legend of Zelda for the Nintendo consoles, and Final Fantasy for the PC, PlayStation, and Nintendo systems are each a highly acclaimed series of games. Another series  of lesser known, but equally important role-playing games in terms of the development of the genre is the Phantasy Star series on Sega consoles. Starting with the Sega Master System and progressing onto the Genesis and now Dreamcast consoles, the Phantasy Star series has (with a single notable exception in the third game of the series) always been developed on the cutting edge of technology. All of the games, in particular Phantasy Star I and the newest, Phantasy Star Online, have pushed the boundaries of their system’s performance. In addition to providing exceptional and innovative game views and game play, the Phantasy Star series has also always provided some of the best, innovative storylines of the genre. The first two games in particular did more with their storyline than any other RPG of their time.

of lesser known, but equally important role-playing games in terms of the development of the genre is the Phantasy Star series on Sega consoles. Starting with the Sega Master System and progressing onto the Genesis and now Dreamcast consoles, the Phantasy Star series has (with a single notable exception in the third game of the series) always been developed on the cutting edge of technology. All of the games, in particular Phantasy Star I and the newest, Phantasy Star Online, have pushed the boundaries of their system’s performance. In addition to providing exceptional and innovative game views and game play, the Phantasy Star series has also always provided some of the best, innovative storylines of the genre. The first two games in particular did more with their storyline than any other RPG of their time.

There were many factors that allowed Phantasy Star to be so innovative in every respect. Sega did manage to develop some very capable systems early in console development. That, coupled with great designers, led to very technologically advanced games. However, Sega’s business practices and general corporate attitude toward the game designer teams are what affected the game development most. In fact, Sega’s success (or lack thereof) with each game seems to parallel changes in the company’s business practices. The changing corporate attitude of Sega can be seen in the quality of the stories and the marketing used for each of the Phantasy Star installments.

Developer History

Sega dates back all the way to 1951 when David Rosen, an American living in Japan, co-founded it. At the time, his company was a Japanese art exporter (and later an art importer as well) and known as Rosen Enterprises. It was not until nearly fifteen years later when Rosen Enterprises merged with a coin-op company that the company’s name was changed to Sega – short for “Service Games.” Before the release of the Master System (or Mark III in Japan) Sega produced a number of great selling and currently well-known arcade games as well as some very crummy games for the first Atari consoles. Frogger and Zaxxon are two of the earliest arcade hits Sega produced.

In 1985 Sega introduced the Mark III to Japan and the next year the company released the American equivalent, the Sega Master System. After many years of poor performance from the console video game market, Sega hoped to capitalize on the new surge in sales generated by the new Nintendo console, the Famicom in Japan, or Nintendo Entertainment System in America. Unfortunately for Sega, Nintendo maintained a stranglehold on the market. Nintendo’s licensing agreements (which were later deemed illegal) prevented third parties from developing games for systems in addition to Nintendo systems. Consequently, very few games were designed for the Master System outside of Sega’s own development teams. By 1988 Sega had only sold two million Master Systems. While this may be a fairly substantial number, it pales in comparison with Nintendo’s sales. The Famicom sold 500,000 units in its first six months. Nintendo easily sold more systems than Sega before the Master System was even released. Up until the takeoff of the next generation of video game consoles, Nintendo commanded nearly 85% of the market for home video games.

Nintendo’s early command of the video game industry can solely be attributed to the man in charge of Nintendo, Hiroshi Yamauchi. His shrewd business decisions did not allow the late-starting Master System to gain very much market share despite the technologically superior system. The Master System beat the Nintendo hands down in nearly every category even with the two systems quite comparable in price (depending on the time of purchase of course). The Master System retailed for $149 for the system with the added light gun. The Master System had an 8-bit, 3.6 MHz processor, while the Nintendo’s 8-bit processor only operated at 1.79 MHz. The Master System could display 52 different colors on the screen out of a palette of 256. The NES could only display 16 of 52 total colors. The Master System also had 64Kb of RAM compared to only 2Kb in the NES. One web site claims that “Games released on the both the SMS and NES have an obviously better look and feel on the Master System.” Considering the huge difference in technology this is not surprising.

One could say that Sega’s foray with Nintendo in the home video game market provided a very important learning experience. Sega did not make the same mistakes when it came to releasing the Mega Drive in Japan in 1988 and the American equivalent, the Genesis, shortly thereafter in 1989. Sega immediately licensed Electronic Arts to produce games for the new 16-bit system. This addition of game titles and the nearly two-year head start on the Nintendo 16-bit system allowed Sega to increase market share. The numbers vary from source to source, but at its pinnacle Sega caught up to if not surpassed Nintendo in market share. According to Segaweb.com, “The Genesis years are often what us Sega fans refer to as the golden age of Sega.” The battle may have been difficult at first–consumers were loath to purchase a new system that had no compatibility with their older games–but Sega’s wonderful new line-up of software titles and impressive graphics slowly enticed consumers away from Nintendo.

Technologically, the Genesis was very impressive. At the time the only existing system boasting similar capabilities was the TurboGrafx 16 by NEC. This system, while marketed as a 16-bit system, actually had two 8-bit processors instead of a 16-bit processor. While the two processors did make the graphics better than any 8-bit system, it was difficult for the system to compete with the Genesis, especially with the system’s lack of software support. The Genesis had a 16-bit processor and the ability to display 64 colors on the screen out of a palette of 512. Complete with 64KB RAM as well as another 64KB of sound RAM, the system was quite capable. When Nintendo finally followed with their Super Famicom/Super NES, the system slowly ate into Genesis market share, but never usurped Sega in the 16-bit war. Like the Master System in the 8-bit war, the Super NES was superior to its biggest competitor, Sega’s Genesis. In fact, the Super NES had a 16-bit processor and 1 Mb of RAM plus an additional 0.5 Mb of video RAM. The Super NES could also display up to 256 colors on the screen at a time out of a palette of 32,768 colors.

Technologically, the Genesis was very impressive. At the time the only existing system boasting similar capabilities was the TurboGrafx 16 by NEC. This system, while marketed as a 16-bit system, actually had two 8-bit processors instead of a 16-bit processor. While the two processors did make the graphics better than any 8-bit system, it was difficult for the system to compete with the Genesis, especially with the system’s lack of software support. The Genesis had a 16-bit processor and the ability to display 64 colors on the screen out of a palette of 512. Complete with 64KB RAM as well as another 64KB of sound RAM, the system was quite capable. When Nintendo finally followed with their Super Famicom/Super NES, the system slowly ate into Genesis market share, but never usurped Sega in the 16-bit war. Like the Master System in the 8-bit war, the Super NES was superior to its biggest competitor, Sega’s Genesis. In fact, the Super NES had a 16-bit processor and 1 Mb of RAM plus an additional 0.5 Mb of video RAM. The Super NES could also display up to 256 colors on the screen at a time out of a palette of 32,768 colors.

In an attempt to support the Genesis, Sega sold a number of unsuccessful peripherals. The Sega CD and 32x were attachments to the Genesis that did not live up to their marketer’s promises. Game titles for these attachments were minimal and the titles created were not considerably better than the standard Genesis games. Consequently, there were not many reasons to purchase these peripherals.

Like Nintendo at the beginning of the 16-bit revolution, Sega had slipped into a slump. New products were not selling. Consumers were anxiously awaiting new games and new systems that typically ended up disappointing. The Saturn, Sega’s 32-bit system, was not able to compete with Sony’s PlayStation. In fact, the Saturn quietly faded into obscurity having never developed enough third party support to develop anything resembling an extensive library of games.

Sega’s most recent attempt at success in the console video game market was with the Dreamcast. This cutting edge 3-D system sold 500,000 units in the first two months of production. Beyond amazing graphics, the Dreamcast also offered something no other system did at the time–interactive online gaming capabilities. While the Dreamcast was extremely successful in its first two years of production, Sega announced that the company will cease to produce the system due to intense competition from Sony’s Playstation 2 and the forthcoming X-Box from Microsoft. While the Dreamcast may not have continued its success as long as Sega wished, it did represent a major victory for Sega. After so many failures following the peak of the Genesis, the Dreamcast demonstrated that Sega could still be successful in the console video game market when managed correctly.

The Games

In the middle of Sega’s brief attempt to win the 8-bit console war, Phantasy Star was created. The outlook was grim at the time. No one at Sega could have honestly thought they had a chance to rival Nintendo by its release in late 1987. By the time the game hit American shelves the next year Nintendo had a commanding lead on console and game sales. Nintendo’s stranglehold on third party development further darkened Sega’s future with the Master System. However, Phantasy Star went on to become the gem of the Master System. Most sites credit it as the best game produced for the Master System.

These accolades can largely be attributed to two people: Yuji Naka and Rieko Kodama. Yuji Naka is credited with the “Main Program” while Rieko Kodama is credited with the “Total Design.” Together these two are largely responsible for the two areas in which Phantasy Star excelled: technological advances and storyline (Click here to see a full list of credits).

The technological advances in Phantasy Star are numerous. To start, it should be noted that it was the first console turn-based RPG. While the concept was not new, the game design was new to consoles. Adapting to this style of game play would have made Phantasy Star a notable game, but Yuji Naka took that further. Three separate views, each representing different situations, were added to Phantasy Star. There was an overhead view for traveling, a wide rear view for fighting enemies, and a first person view for navigating tunnels and caves. The graphics for tunnel exploration drew the most attention, and to this day are still very good. The detail is great, and the smoothness of the scrolling is extremely impressive. This quality probably could not have been achieved on the NES due to its inferior capabilities. In addition to these advances, combat animations were also added during the battle scenes. Visible attacks against enemies provided a tangible differentiation between the Phantasy Star and board game RPGs.

While Phantasy Star may have been designed on the cutting edge of technology, it was the storyline that truly captured the hearts of those who played the game. Rieko Kodama wonderfully blended science fiction and myth to create an adcventure that has withstood the test of the ages. Only within the past year was Phantasy Star inducted into the Gamespy.com Hall of Fame.

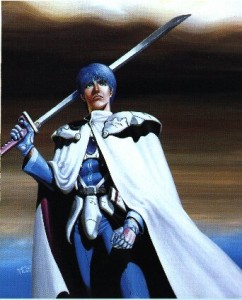

One of the most striking differences between this game and other RPGs is the gender of the lead character. Alis Landale, the leader of the group, sets out in this game to defeat the evil Lassic after Lassic kills her brother. The only game at the time (and for quite a while longer) with a female lead character was Nintendo’s Metroid. Contrary to today’s average “lead female character,” Alis is not scantily clad, or in any way a sex symbol. She is simply a strong woman on a mission to avenge her brother’s death.

In order to fulfill her mission, Alis is aided by high tech science fiction. At her and her parties disposal over the course of the game there is a hovercraft, a land rover, an ice digger, and a space ship. Each of these vehicles allows Alis and her party to explore more of the Algol star system.

The most amazing aspect of this game is its seamless introduction of myth into the plot. Early on the player finds that Medusa changed Odin to stone. In order to heal Odin, Alis must find Perseus’ shield. “According to our legends, the very shield Perseus used to overcome Medusa is buried on the small island in the middle of a lake.” (Text from Phantasy Star). This reference to Greek mythology is very clear, but does not completely describe the reference. The star system in which the Phantasy Star games are set actually has a real life equivalent. “Algol is an eclipsing binary star located in the Perseus constellation. In fact, the ‘ghoul’ star was thought to represent the eye of Medusa, due to its variable brightness” (Algol).

In addition to the constant references to Medusa and Perseus, there are a number of other myth-like events in Phantasy Star. “When Myau eats the Nuts of Laerma, he becomes clothed in flame and emits a blinding light. When he is visible again, he has been transformed into a beautiful winged beast. Myau flaps his wings proudly” (Text from Phantasy Star I). Events like this gave Phantasy Star a fantastic, mythical feel. It made the game difficult to put down, and easy to spend hours playing at a time.

Shortly after the release of the Genesis in 1989 Sega released Phantasy Star II, the follow-up to their most revered Master System game. With Yuji Naka and Rieko Kodama in charge of programming and design respectively, the sequel worked within the bounds dictated by the original game (Click here to see a full list of credits). Just like Phantasy Star, its first sequel had a captivating storyline and made wonderful use of the new Genesis technology. There was one major change though. Many of the mythical qualities of the first game were not in the second. Instead of fighting mythical beasts, the story describes the enemies as genetic and computer experiments gone wrong. This changes the story for the better. Instead of rehashing the same plot, a new menace has caused problems in Phantasy Star II. Only near the end of the game does the player realize that the evil behind Lassic in the first adventure is also the being behind the problems in Phantasy Star II.

Shortly after the release of the Genesis in 1989 Sega released Phantasy Star II, the follow-up to their most revered Master System game. With Yuji Naka and Rieko Kodama in charge of programming and design respectively, the sequel worked within the bounds dictated by the original game (Click here to see a full list of credits). Just like Phantasy Star, its first sequel had a captivating storyline and made wonderful use of the new Genesis technology. There was one major change though. Many of the mythical qualities of the first game were not in the second. Instead of fighting mythical beasts, the story describes the enemies as genetic and computer experiments gone wrong. This changes the story for the better. Instead of rehashing the same plot, a new menace has caused problems in Phantasy Star II. Only near the end of the game does the player realize that the evil behind Lassic in the first adventure is also the being behind the problems in Phantasy Star II.

Phantasy Star II‘s major advances are in the technological side of the game design. Yuji Naka programs a great game with the new 16-bit Genesis. The still shots at the beginning and end of the game when a story is being told are wonderful. They clearly demonstrate the Genesis’s superior graphics capabilities. Character detail improved with the better quality system, and so did detail in the fight scenes. In caves or tunnels one can also see a new feature of the Genesis-two independent scrolling backgrounds. The party walks as in the outside view, but in the front of the screen there is a slower scrolling network of pipes that obstruct some of the players view. This feature was certainly brand new to RPGs.

Phantasy Star III was an unfortunate mess. Released in 1991, Sega decided not to have Yuji Naka and Rieko Kodama plan and design this game (Click to see a full list of credits). Consequently the game hardly resembles either of the first two. Many people disliked the game for its departure from the series. Others found it unoriginal and uninspiring. Seeing that it was designed for the Genesis very shortly after the first game, little advancement had been made in the use of the Genesis system. The graphics were not any better, and unfortunately the story was lacking. The only saving grace for Phantasy Star III was its feature that allowed for four different endings. In the game the player plays three different generations of characters. Each generation there is a choice of who to marry. The player’s choice determines the next generation of the game. An intriguing idea, but the result was four different endings to one sub-par game.

Phantasy Star IV, released in 1994, is a return to the original games. Again, Yuji Naka and Rieko Kodama combine to design and program this game. After the failure of Phantasy Star III, Sega desperately wanted another quality game in the series to boost waning sales of Genesis games. Rieko Kodama herself attested to such in the Phantasy Star Compendium:

I was told by the company to make the RPG as soon as possible. They also asked me to try and bring together the original scenario writers, illustrators, and character designers…

Phantasy Star IV was quite a success. The game returned to the general storyline of the first two games and brought with it better designed graphics and a great story. Early in the game the female lead character dies leaving Chaz, an apprentice fighter, to continue the party’s quest. This is sad moment in the game. In order to advance the main character must die. Similar circumstances can be found in Final Fantasy games.

Sega released the newest installment in the series, Phantasy Star Online, for the Dreamcast in late 2000. Designed by Sonic Team (a group headed by Yuji Naka), Phantasy Star Online is the first console game designed to be played with people from across the world. In fact, cooperation is necessary to succeeding in the game. In order to facilitate cooperation, especially with a potential language barrier, many prewritten phrases are available to select from, as well as symbols so that one can communicate with someone who does not speak the same language. This clearly is a huge technological advance over previous video games. It remains to be seen if the future of RPG design will involve cooperation over the Internet.

The Influence of Sega’s Business

Throughout the development of the Phantasy Star games there was one outside factor that influenced game design–Sega’s business. Much can be said about each game when examined in context with the state of the company at the time. As the first Phantasy Star was being designed, the market leader was quite apparent. No one in the world doubted that Nintendo had a stranglehold over the console video game market. Sega also knew that the minimum number of Master System games certainly was not helping their sales. Consequently, Sega had to concentrate on their advantage in the market, technology, and use that to create amazing games. Phantasy Star was one of these amazing games. The designers knew that the game had to be great for it to sell, so they made an absolutely amazing game – arguably the best looking 8-bit game ever made. As Naka and Kodama set forth to begin designing the second Phantasy Star game, they again found themselves in a very similar situation. At the time Phantasy Star II was released, Sega had yet to gain very much market share on Nintendo even with the Genesis being the only true 16-bit machine on the market. Again, Phantasy Star II had to be a very good game. Like the original, the sequel needed to not only capture the attention of those owning a Genesis, but it also needed to cause people to purchase one. The focus on great software is what finally pushed the Genesis ahead of Nintendo. Great games designed within and smart third party licensing drove sales of Genesis systems. However, this mad rush to produce software hurt Sega in Phantasy Star III.

Phantasy Star III may be a departure from the earlier Phantasy Star games, but it still follows Sega’s business decisions. By 1991, when this game was released, Nintendo had released its Super NES. Feeling the heat of competition, Sega needed to maintain its market share in the 16-bit console war. Unfortunately for Sega, Square was still producing its well-known role-playing games for Nintendo. Sega quickly found itself competing with 16-bit Final Fantasy games and other quality role playing games from Nintendo. In response, Sega rushed another Phantasy Star through production in less than two years. It’s quite possible that the timeframe in which Sega wanted the game made it impossible for Naka and Kodama to work on Phantasy Star III because they had other projects in the works (Naka is responsible for Sonic the Hedgehog). Nonetheless, Sega’s haste led to an unsuccessful, less than stellar game. It seems that Sega counted more on reputation than quality to sell this game.

Phantasy Star III may be a departure from the earlier Phantasy Star games, but it still follows Sega’s business decisions. By 1991, when this game was released, Nintendo had released its Super NES. Feeling the heat of competition, Sega needed to maintain its market share in the 16-bit console war. Unfortunately for Sega, Square was still producing its well-known role-playing games for Nintendo. Sega quickly found itself competing with 16-bit Final Fantasy games and other quality role playing games from Nintendo. In response, Sega rushed another Phantasy Star through production in less than two years. It’s quite possible that the timeframe in which Sega wanted the game made it impossible for Naka and Kodama to work on Phantasy Star III because they had other projects in the works (Naka is responsible for Sonic the Hedgehog). Nonetheless, Sega’s haste led to an unsuccessful, less than stellar game. It seems that Sega counted more on reputation than quality to sell this game.

Phantasy Star IV was also rushed into production; however, Sega was quite conscious about the mistakes not to make. This final Phantasy Star for the Genesis was released as Sega began to transition development over to the Saturn. Partially needed to save face for the series, partially needed as one last great RPG for the Genesis, Phantasy Star IV production was created more in line with the first two in the series. Sega knew that sales for this game would not be guaranteed because of its predecessor. Phantasy Star III may have been more of a deterrent than anything else for those deciding whether or not to purchase Phantasy Star IV. Consequently, Sega brought Kodama and Naka together to create this fourth Phantasy Star. Though Sega did express urgency to complete this game because of its market position competing against Nintendo, Sega also learned from the mistakes it made with Phantasy Star III.

Phantasy Star Online‘s creation resembles that of Phantasy Star II most. Poised in the short term as the only system of its kind, the Dreamcast before the release of the PlayStation 2 resembled the Genesis before the release of the Super NES/Super Famicom. Similarly to the second game, Phantasy Star Online does an amazing job of taking advantage of its new, available resources on the Dreamcast. From a business perspective, this was quite necessary. The Dreamcast at the time was vying for acceptability in the console market. An amazing game was necessary to woo more consumers over to the Dreamcast. While it may not have saved the Dreamcast, Phantasy Star Online did succeed in selling a lot of consoles. It, like Sega needed, caused many people to invest in a Dreamcast.

Sega’s Phantasy Star Marketing

While some of this analysis may be speculative, examining the marketing employed by Sega enforces many of ideas presented. Sega released a single commercial for each of the first four Phantasy Star games in Japan. While the dialogue may be in Japanese, the message of each commercial is not difficult to discern. In the commercial for the first Phantasy Star, there is a mixture of real acting and screenshots from the actual game. The music in the commercial and quickness of the shots emphasize the action in the game. The opening shot of a wicked beast sneaking up on Alis also piques interest in the story of the game. The closing shot of Alis holding her sword high triumphantly also includes two words under her: “4M” and “FM sound”. This shot carries with it the ultimate message of the commercial- Phantasy Star is a high quality game. In a time of cartridges measured in kilobits, Phantasy Star was a 4 Mega bit game. That of course translates to better graphics, and a longer story with less repetition in characters, enemies, and terrain. FM sound again emphasizes the quality of the sound in the game. Clearly Sega realized that the only angle to attack the market successfully was with technology. It is not a stretch to assume that the game designers, like the rest of the company, knew that better technology was the angle to take when creating this game.

The commercial for Phantasy Star II emphasized game quality even more than the Phantasy Star I commercial. In this commercial only shots from the game are used. Starting with the view while in battle mode, the commercial cycles through all the views in the game and also shows a multitude of enemies before ending the commercial with the phrase “16-Bit RPG” on the screen. Again, Sega differentiates its product from others through technology. There weren’t any other 16-Bit RPGs at this time.

Sega’s commercial for Phantasy Star III displayed exactly what was apparent in their design process – arrogance. Never once in the commercial is there footage from the actual game. Instead all the viewer sees is a choreographed dance with swords, and the phrase “King of RPG.” The ridiculously apparent attempt to sell Phantasy Star III solely on the success of the previous two games cannot be overlooked.

The commercial for Phantasy Star IV is a return to the style of the first commercial. Far more dramatic than that of the others, this commercial starts with the game title screen appearing out of the explosion of a planet and includes lengthy action footage of characters narrowly escaping destruction. Mixed within are great cuts to different views of the actual game mostly highlighting the quality of the graphics. Sega clearly reverts to their old strategy of hyping the game, not the name. Interesting to note, this commercial is twice as long as the other commercials, lasting 30 seconds. Like the first commercial, emphasis is placed equally between the intriguing story and the graphical quality of the game.

Sega influenced role-playing game design with its Phantasy Star series. Attention to graphics in a role-playing game had never been as important before Phantasy Star I and II. The graphics immersed the player in the game, and the storylines were some of the best ever written. In the original Phantasy Star there was also a wonderful mix of myth and science fiction like never before seen in a role-playing game. All these qualities made this series one to remember, and one to emulate.

Not only do some of the Phantasy Star games clearly represent innovations in the role playing game genre, but the success and quality of the series also shows the ups and downs of Sega’s business. During the 8-bit console war Sega suffered from lack of software. Their answer was to make better software than Nintendo and hope quality would outweigh quantity. Had Sega entered the market at the same time as Nintendo the NES would have faced serious competition. While Nintendo remained complacent with its 8-bit system, Sega leapt ahead to 16-bit technology while maintaining their practice of producing technologically superior games. Phantasy Star II succeeded because of this. By the time Phantasy Star III was released, Sega had become somewhat complacent, like Nintendo had been as Sega introduced the Genesis. Sega rushed the design phase with different designers and produced a sub-par game. Phantasy Star IV and Phantasy Star Online were returns to the original practices because Sega had fallen behind in the console war again. Sega could not afford to produce a sub-par game. The state of Sega’s business affected each of the Phantasy Star games sometimes for the best, sometimes for the worst.

Not only do some of the Phantasy Star games clearly represent innovations in the role playing game genre, but the success and quality of the series also shows the ups and downs of Sega’s business. During the 8-bit console war Sega suffered from lack of software. Their answer was to make better software than Nintendo and hope quality would outweigh quantity. Had Sega entered the market at the same time as Nintendo the NES would have faced serious competition. While Nintendo remained complacent with its 8-bit system, Sega leapt ahead to 16-bit technology while maintaining their practice of producing technologically superior games. Phantasy Star II succeeded because of this. By the time Phantasy Star III was released, Sega had become somewhat complacent, like Nintendo had been as Sega introduced the Genesis. Sega rushed the design phase with different designers and produced a sub-par game. Phantasy Star IV and Phantasy Star Online were returns to the original practices because Sega had fallen behind in the console war again. Sega could not afford to produce a sub-par game. The state of Sega’s business affected each of the Phantasy Star games sometimes for the best, sometimes for the worst.

The complete release chronology is as follows:

- Phantasy Star, Sega Master System (1988)

- Phantasy Star II, Genesis (1989)

- Phantasy Star II Text Adventures, Mega Drive [Mega Modem downloads] (1990)

- Phantasy Star III, Genesis (1991)

- Phantasy Star Adventure, Game Gear (1992)

- Phantasy Star Gaiden, Game Gear (1992)

- Phantasy Star Anniversary Edition, Mega Drive (1993)

- Game no Kandzume: Phantasy Star II Text Adventures, Mega CD (1994)

- Phantasy Star IV, Genesis (1994)

- Phantasy Star Collection, Saturn (1998)

- Phantasy Star Online, Dreamcast (Jan. 2001)

- Phantasy Star Online Ver. 2, Dreamcast (Sept. 2001)

- Phantasy Star Online, Windows PC [Japan] (2001)

- Phantasy Star Online, Windows PC [Taiwan] (2002)

- Phantasy Star Collection, Game Boy Advance (2002)

- Phantasy Star Online: Ep. 1 & 2, GameCube (2002)

- Phantasy Star Online: Ep. 1 & 2, Xbox (2003)

- Phantasy Star Online: Ep. 1 & 2 Plus, GameCube [Japan] (2003)

- Phantasy Star Online: Ep. 3 C.A.R.D. Revolution, GameCube (2004)

- Phantasy Star Online Blue Burst, PC (Spring 2005)

- Phantasy Star Universe, PlayStation 2, PC, & Xbox 360 (2006)

Regarding the 6th paragraph, Megadrive was first released in Japan in 1988, the Genesis in the US was the one released in 1989.