For most of the world who knows or cares about such things, VALIS is the name of a science fiction novel with a schizophrenic narrative written by the late Philip K. Dick. The word is an acronym, and stands for Vast Active Living Intelligence System. Dick coined the term in an attempt to describe a series of religious experiences he tried to come to terms with right up until his death during the final phases of the filming of Blade Runner, based on his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, starring Harrison Ford.

Dick’s encounter with higher realities wasn’t your average garden-variety mystical experience or UFO sighting. While the details as he provides them bear striking resemblance to his colleague Clifford D. Simak’s book Time is the Simplest Thing, published decades earlier, and is therefore perhaps ascribable to another case of an author sublimating and recapitulating later the work of an earlier author, Dick’s VALIS created shock waves which Simak’s SF classic never did. Writing in the late 70s and early 80s about an experience from 1974, Dick used terms more familiar to today’s computer-literate society than to the audience at the time. He described VALIS as an information system, which broadcast tight “packets” of data to the human audience, data intended to reawaken humanity’s knowledge of its lofty estate and noble mission. Dick wasn’t well-known during his lifetime outside of the SF community. He was rather more respected in France, Germany and perhaps Japan than in his native America, and his works were translated into a number of languages. After his death he became very popular, and a number of cinematic adaptations of his works have been and are being made, the latest being Minority Report.

Dick’s encounter with higher realities wasn’t your average garden-variety mystical experience or UFO sighting. While the details as he provides them bear striking resemblance to his colleague Clifford D. Simak’s book Time is the Simplest Thing, published decades earlier, and is therefore perhaps ascribable to another case of an author sublimating and recapitulating later the work of an earlier author, Dick’s VALIS created shock waves which Simak’s SF classic never did. Writing in the late 70s and early 80s about an experience from 1974, Dick used terms more familiar to today’s computer-literate society than to the audience at the time. He described VALIS as an information system, which broadcast tight “packets” of data to the human audience, data intended to reawaken humanity’s knowledge of its lofty estate and noble mission. Dick wasn’t well-known during his lifetime outside of the SF community. He was rather more respected in France, Germany and perhaps Japan than in his native America, and his works were translated into a number of languages. After his death he became very popular, and a number of cinematic adaptations of his works have been and are being made, the latest being Minority Report.

His first breakthrough was Man in the High Castle, which deals with an alternate reality in which the Axis won World War II. The action is set in occupied North America and, characteristically, involves an act of mercy performed by the main character, Japanese liaison Tagomi stationed in San Francisco. Dick did extensive research on WWII itself before he wrote the book, but then based the narrative on results from the I Ching, the ancient Chinese divination system. The result was spellbinding, and Dick won the Hugo, the SF community’s equivalent of the Oscar. The book was translated into Japanese.

His struggle to describe what had happened to him in 1974 resulted in several novels, including Divine Invasion, VALIS, Radio Free Albemuth, and Transmigration of Timothy Archer; based on the life and times of the 1960s radical Episcopalian archbishop of California, the reverend James Albert Pike. Pike used to do things like lead his Bay Area congregation of elderly matrons in Zen meditation on Sundays. He was also arrested in Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and deported for holding certain views regarding race and human equality. When he began doubting the doctrine of the Trinity, and began saying in public the Holy Spirit was perhaps tacked on as an afterthought to draw in the early Greek congregation with their notions of logos in the early days of Christianity (as Dick retells it), Pike became the subject of what was probably the last Episcopalian heresy trial. Pike died under what seemed to Dick mysterious circumstances while in Palestine. Dick indicates in his novel about his friend Pike that he believed there was some connection between Pike’s death and the startling statements that were then issuing forth from the Dead Sea Scrolls Commission in the person of John Allegro, the only non-sectarian person within the body charged with translating the scrolls. Ultimately Dick put Pike’s death down to the times, and felt he had been assassinated somehow, as had Martin Luther King, Jr., President John F. Kennedy, and his brother, Robert Kennedy.

Dick and his wife had also been involved in Pike’s project to contact his son, who had committed suicide, by the use of a spirit medium.

While Dick may have claimed Pike was denying the Trinity, the body of Dick’s work leads one to believe he was writing about a phenomenon which roughly fits into some classical conceptions of the Holy Spirit, and a vast, information-processing Holy Spirit at that.

Dick died in 1982.

On December 8, 1986, the Japanese video game manufacturer Telenet Nihon issued a new game created by its Wolf Team for users of the Nippon Electric Company’s PC 8801 computer. It’s essential to realize the NEC PC series is not the same thing as the IBM PC. The NEC computers were little known outside Japan, but offered significantly more possibilities for graphics and sound than the early IBMs. PC means personal computer, but they seem to have been intended for use in Japanese offices. Their gaming potential was quickly realized. The software library for the machine is a testament to the economic and cultural boom times in 1980s Japan. The PC series eventually included the 9801, later the 9821 (an expanded version of 9801) and more recently the 98DO, which breaks with tradition and seems intended to run Microsoft Windows.

The Japanese video games of the period, and Japan fairly started the video game craze with Space Invaders, Donkey Kong, and Pac-Man, involve a very complicated synthesis of cultural, religious and mythical elements from around the globe, placed in a Japanese context. That’s nowhere more true than with Japanese computer games. Valis was one such game.

Valis: the Fantasm Soldier, or Mugen Senshi Valis in Japanese, begins with an eight-sided blue jewel ringed in gold and gold braid, with the words TELENET scrolling up from mid-screen to overlap the jewel, and underneath “A WOLF TEAM PRESENTS.” accompanied by two falling gong tones. That sets the cinematic and musical tone for all later versions and ports of the game. The next screen, the intro proper, will look familiar to gamers who have played ports for the Genesis, Super Nintendo, and others. Kanji for Mugen Senshi fading top-to-bottom from white to light blue in the upper-left area of the screen, followed on the right side by the words The Fantasm Soldier in light blue, with Valis written in vermilion red in katakana across the entire middle of the screen, with credits much smaller underneath in white:” Created by A WOLF TEAM” and “Producted by TELENET JAPAN Co., LTD. Copyright 1986.” The katakana title Valis (or Vaarisu, technically) flashes like lightning against rolling pink mists or clouds scrolling from left to right in the center third horizontal part of the screen. Shadows from the katakana lie black somewhere between the flashing pink clouds and flashing bright red letters. The intro screen plays an endless soundtrack of the Valis theme song, probably familiar to players of all ports.

Once the space key on the PC 8801 keyboard is pressed, the player is led onto another introduction, more elaborate and containing the anime Valis would become famous for. (The return key plunges you straight into game play at this point). Scrolling from left to right you see a wall, what seems to be a Pepsi vending machine, a garbage can and a small blue book bag next to the garbage can. Then a young girl with her back turned to you is seen standing underneath a storefront canopy awning in a doorway. She’s wearing a sailor-suit girl’s school uniform, and has blue hair. Japanese subtitles show she’s wondering when it will stop raining. She begins to remember a strange dream, but is interrupted by her schoolmate Reiko, with flaming pink hair and wide eyes with red irises. The long and the short of it is Reiko has come to say goodbye, she’s leaving town, but Yuko, our main character, doesn’t understand why and thinks she’s a very strange girl. Yuko bats her big blue eyes. The way the programmers coordinated the dialogue with lip movements is uncanny. Neither girls actually speaks words in the first version of Valis. Instead, Reiko issues click sounds which correspond exactly, pause for pause and syllable for syllable, with the subtitles underneath, and her eyes bat during the pauses. Yuko does the same thing, only with slightly higher click tones. When Yuko is thinking, her thoughts are displayed underneath in the subtitles, but her lips don’t move and there are no click sounds. Someone spent a lot of time and gave a lot of attention to the timing.

Once the space key on the PC 8801 keyboard is pressed, the player is led onto another introduction, more elaborate and containing the anime Valis would become famous for. (The return key plunges you straight into game play at this point). Scrolling from left to right you see a wall, what seems to be a Pepsi vending machine, a garbage can and a small blue book bag next to the garbage can. Then a young girl with her back turned to you is seen standing underneath a storefront canopy awning in a doorway. She’s wearing a sailor-suit girl’s school uniform, and has blue hair. Japanese subtitles show she’s wondering when it will stop raining. She begins to remember a strange dream, but is interrupted by her schoolmate Reiko, with flaming pink hair and wide eyes with red irises. The long and the short of it is Reiko has come to say goodbye, she’s leaving town, but Yuko, our main character, doesn’t understand why and thinks she’s a very strange girl. Yuko bats her big blue eyes. The way the programmers coordinated the dialogue with lip movements is uncanny. Neither girls actually speaks words in the first version of Valis. Instead, Reiko issues click sounds which correspond exactly, pause for pause and syllable for syllable, with the subtitles underneath, and her eyes bat during the pauses. Yuko does the same thing, only with slightly higher click tones. When Yuko is thinking, her thoughts are displayed underneath in the subtitles, but her lips don’t move and there are no click sounds. Someone spent a lot of time and gave a lot of attention to the timing.

After the third introduction is over, Yuko drops into level one, where she runs along a sideways scrolling screen battling menacing flying squid and so on with the Valis sword. There is no explanation of why she is now fighting monsters. All we are told is “ENTRY TO ACT1, ‘TOWN’, MAY THE VALIS BE WITH YOU!” Control over Yuko is problematic, she doesn’t seem to move the way you want her to. She does a lot of jumping around the city, and when she dies, the hilt of her Valis sword becomes a small cross, as if marking the grave. Rogles is called Logless in the first version. The dungeon of his castle in ACT9 is a Lovecraftian procession of walking monstrosities (seemingly mostly based on sea-food items) and turf-encrusted ledges of blue earth suspended in mid-air. The music is menacing and eldritch, and uses low and high tones on the PC 8801’s various available sound channels very nicely.

The closing scene is dramatic: the screen scrolls from left to right, again the initial introduction screen. Pan on the blue book bag: we see it’s a small briefcase, perhaps a valise? Yuko is gone from the doorway. Underneath the titles begin roll. The complete musical score is listed under BGM (what that stands for I don’t know), and the screen then turns into the final rolling credits of a film, with authors’ names in Japanese characters, eventually stopping on Nihon Telenet written in Japanese. The association with film is unavoidable.

Valis was released for the Sharp X1 computer and the MSX computers in December of 1986 as well. The Sharp X1 intro is identical, except the katakana characters for Valis don’t flash, while the scrolling pink clouds in the background do, they flash yellow. The initial anime introduction is the same. Reiko and Yuko lack the clicks accompanying their speech.

The fade-out from the anime to ACT1 “TOWN” is accomplished differently as well. Gameplay is even more irksome than with the PC 8801. The machine doesn’t seem able to poll two keys at once, so it’s impossible to run and jump at the same time, although that may be purely a result of using an emulator to run the game, and the original hardware might have been different. The final credits are identical to the PC 8801’s.

The MSX wasn’t a single computer per se. It was a standard architecture worked out primarily by Microsoft and ASCII for manufacturers to present the market with computers that ran one another’s software. The standard never caught on in the US, but it was important in Japan, and MSX enthusiasts also existed in the Middle East, South America, and elsewhere. It was based around the Z-80 microprocessor by Zilog, which had inherent limitations in the amount of memory it could address. Valis for MSX cuts to the chase. It opens with a splash screen, the kanji Mugen Senshi followed by English The Fantasm Soldier, Valis written in red in katakana across the screen, a copyright notice by Telenet, then goes right into its own specific introduction, which involves one of several worlds: the city of the first level, a highly simplified version of the Lovecraftian world described above and a sort of candy-cane pinkish sugar-coated world, Santa Claus on mescaline, as well as intermediate worlds. Blue, pink, red and orange Spanish moss finds fertile ground in the MSX graphics. These are presumably levels within the game.

MSX game play is somewhat better. The lower-resolution graphics mean that it’s easier to make out what’s going on on the screen. MSX Valis serves Coke, not Pepsi, by the way.

In March of 1987 Telenet released Valis for the NEC PC 9801M/VM and in Une of ’87 for Fujitsu’s personal computer the FM-77AV. I would like to hear from anyone who has these games or information about them, complete anonymity guaranteed. Please write me at storge@hardcore.It.

Also, a version of Valis II was supposedly released for the first generation of MSX computers in August of 1989. I would be very grateful for information sent to the address above, as well as data for Valis II for PC 9801.

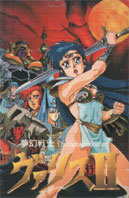

Valis II is best known on the MSX2 systems, but was also released in July of 1989 for the PC 8800 series, in August of the same year for the PC 9801, and in December for the Sharp X68000, which was graphically superior to the Sharp X1 (described as a full-fledged computer with a PC Engine on board). Valis II also came out on the NEC PC Engine (a.k.a. Turbo Grafx) on July 31st of 1989 as CDROM2 media (Valis I for PC Engine was released on March 19, 1992, a year after Valis IV came out for the same machine on August 23, 1991 and before the Valis Visual Collection CD was marketed in 1993).

On the Sharp X68000, the splash screen is a gradually growing title in green “RENO” while a Kermit-the-frog type voice announces “Renovation Games!” Renovation was a Telenet subsidiary which eventually marketed Valis outside of Japan from its headquarters in Los Gatos, California. The opening screen features a female voice calling to Yuko in Japanese. The screen resolves into the face of a woman. Then Yuko is seized by some monster and thrust squirming into the air. She screams, and then we see her wake up in a cold sweat in her bed. Outside a large yellow moon rises rapidly over skyscrapers. A shadow appears on Yuko’s bedroom curtains in the shape of the monster. The shadow grows over Yuko’s face, and her eyes grow wide as she screams. The Valis II logo, this time in golden katakana, glitters on the screen, and updated theme music plays for a short time until the user is instructed to insert floppy diskette D in drive 0 and then has the choice to go into act 1 or load a saved level. “RUSH INTO ACT1! SUDDENLY VOGUES MAKE AN UPON YOU!” the title screen to level 1 informs. “THROW AWAY YOUR PREPLEXITY! BELIEVE VALIS POWER.” the program recommends as Yuko dies a screaming death and is then ushered away by what might be described as a witch flying inside an energy ball. The vending machines have become generic compact green contraptions.

On the Sharp X68000, the splash screen is a gradually growing title in green “RENO” while a Kermit-the-frog type voice announces “Renovation Games!” Renovation was a Telenet subsidiary which eventually marketed Valis outside of Japan from its headquarters in Los Gatos, California. The opening screen features a female voice calling to Yuko in Japanese. The screen resolves into the face of a woman. Then Yuko is seized by some monster and thrust squirming into the air. She screams, and then we see her wake up in a cold sweat in her bed. Outside a large yellow moon rises rapidly over skyscrapers. A shadow appears on Yuko’s bedroom curtains in the shape of the monster. The shadow grows over Yuko’s face, and her eyes grow wide as she screams. The Valis II logo, this time in golden katakana, glitters on the screen, and updated theme music plays for a short time until the user is instructed to insert floppy diskette D in drive 0 and then has the choice to go into act 1 or load a saved level. “RUSH INTO ACT1! SUDDENLY VOGUES MAKE AN UPON YOU!” the title screen to level 1 informs. “THROW AWAY YOUR PREPLEXITY! BELIEVE VALIS POWER.” the program recommends as Yuko dies a screaming death and is then ushered away by what might be described as a witch flying inside an energy ball. The vending machines have become generic compact green contraptions.

MSX2 follows the introduction faithfully, with chunkier graphics and subtitles replacing the speech. Some kind of Japanese stringed instrument plays in the background as clicks mark syllables in the dream woman’s monologue. Play is again helped by the lower graphics capabilities. The witch’s energy ball flames as if it’s reentering the earth’s atmosphere in the later, molten rounds of the game.

Valis II for PC 8801 looks and sounds superior to the two ports detailed above. The introduction betrays the same meticulous care given to matching lip and syllable noted earlier, and act 1’s title screen fills in a blank from the Sharp X68000 version: “Rush into Act 1! Suddenly vogues make an attack upon you!” The vending machines seem to have vanished altogether. When Yuko dies screaming, her scream is surprising, it elicits a sense of alarm in the player, who is again told to “Throw away perplexity! Believe Valis power!”

With Valis II we reach the end of the initial stage in the life of the game. Valis II for PC Engine continues the wacky animal theme and takes it to new heights, with all manner of flying squirrel and rogue blue skunk lurking about. The visual style of Valis II for PC Engine, the frosty or hazy look of the city skyline at night, is present in the Sharp version of Valis II. The PC 8801 version’s crispness just makes it all the better. Readers will likely be familiar with Valis SD (superdeformed, or cutesy Valis, misnamed Syd of Valis for the North American gaming audience) and Valis I and III for Sega consoles, and also will have access to information on the PC Engine/Turbo Grafix versions. While the round criticism of the Super Nintendo port of Valis IV, a.k.a. Super Valis, a.k.a. Red Moon Rising Valis, a.k.a. Mighty Maiden Valis, would tend to force the conclusion that the Valis series has come to an end, it’s not so. Valis music continues to be ripe material for fans to improve and improvise upon. Valis fan pages refuse to go away. One ambitious project by a Japanese author is busy producing virtual 3D screen images of Valis, Yuko and themes related to the game. Another group in Japan has produced graphics and a demo for a Valis for Windows game. Valis the book and VALIS the video game are like an infectious virus that refuses to completely quit the now global cultural scene. In Philip K. Dick’s conception VALIS was reordering our world, gradually subsuming a deficient reality and making a sick world well, without our knowledge. Like a thief in the night, or as Dick said, like a killer-T immune cell released into a diseased part of the cosmic body.

Besides Valis the video game, there was also the Telnet Music Box program released for NEC and Sharp computers, various music CDs containing Valis music, an OVA or original anime (meaning animated) presentation video, a small production of rosin Valis swords and costume elements as well as girls’ jewelry, a Valis T-shirt as a prize in a promotional contest, probably Valis Japanese comics (known as manga in the comics world and in Japanese) and spin-offs, including Valis motifs in animated serials like Slayers!, Slayers Try!, and others (the main character in Slayers, Lina Inverse, may in fact be Lena from Valis III for PC Engine). It also got honorable mention in the popular game Record of Lodoss War, where Valis appears on a map as the name of a country. Valis III for PC Engine also contains hidden bitmaps which indicate a contest called Valis roulette, with prizes to be doled out by Telenet. One of the bitmaps is instructions on how to enter a secret code onto a post-card and where to send the post-card (to Telenet headquarters).

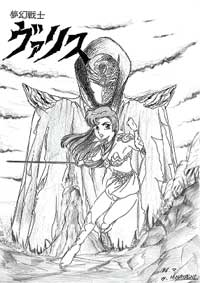

Blue-haired school-girls in sailors’ uniforms didn’t originate with Valis, but Yuko became their incarnation, and she continues to be the subject of Japanese anime art. She’s also made cameo appearances in other venues. It seems clear that from the beginning the creative team that cooked up Valis the video game intended it to become an animated film and, eventually, a television series. In one of the alternate realities in Dick’s novel Valis is a cheap sci-fi film about a satellite broadcasting information threatening to people in high places. The generals decide to destroy the satellite. In other places Dick references Valis as an American film from 1975 which dealt with the impermanence of what seems to be reality. Valis the video game poses the same question to its young audience: did what just happened really happen, or was it a dream, a fantasy? Are there other worlds? In the case of the game as in Dick’s novel, the answer comes from the evidence: the piece of scarf tied around Yuko’s arm in remembrance of slain Reiko, the information that saved Dick’s son Chris from an undiagnosed hernia. In both cases the final decision rests with the individual, there is no proof that would stand up in court. Dick and Pike probably agreed that it was futile to try to prove intellectually the existence of God, in the end it’s up to the individual to decide. The Wolfteam left it up to the player to decide how serious to take the game.

Valis never became a children’s cartoon in Japan, at least not a widely-known one (the OVA was a cartoon, after all). In exactly the same way Dick envisaged it, Valis the videogame interposed into popular culture and into the terms of popular culture an essential question about the nature of reality itself. Dick’s novel ends with a cartoon, after all: the author is pondering all that has happened, and proof arrives in the form of Felix the Cat. I like to imagine that Dick’s authority will continue to grow in years to come, that his stature will grow as an important writer from the 20th century, a writer of serious literature in terms the wider contemporary culture was capable of understanding, in accessible format if that’s a better way to say the same thing. I like to imagine, say, 50 years from now Dickheads, as Dick’s fans call themselves, will be collecting Valis videogame memorabilia — T-shirts, fantasm jewelry, the coveted OVA — in the same way Tagomi, the Japanese ambassador to the occupied West Coast of the United States, collected antique American popular culture items, comics and toys and other items.

Valis the video game’s original creative team included the following individuals: the original game design was by H. Hayashi with help from Y. Mitsuhashi and special thanks to M. Akishino. The program (apparently originally written in Z80 source code and converted to other CPU machine code instructions) was written for NEC PC 8801 by M. Akishino with help by M. Hanawa, for Sharp X-1 by M. Yamamoto, for MSX by T. Anazawa, for FM77AV by S. Iizuka and for NEC PC-9801 by O. Sato.

Valis the video game’s original creative team included the following individuals: the original game design was by H. Hayashi with help from Y. Mitsuhashi and special thanks to M. Akishino. The program (apparently originally written in Z80 source code and converted to other CPU machine code instructions) was written for NEC PC 8801 by M. Akishino with help by M. Hanawa, for Sharp X-1 by M. Yamamoto, for MSX by T. Anazawa, for FM77AV by S. Iizuka and for NEC PC-9801 by O. Sato.

Graphics directors were H. Hayashi and M. Takahashi. Graphics working staff were M. Takahashi, D. Kiyasyu, S. Shiino, H. Toriumi and T. Tanaka.

Music was composed and arranged by S. Ogawa under advisement from O. Sato.

http://twin.coco.co.jp/valis/game has alternative information on the origin of the name of the videogame. The webpage is in Japanese.

Character designs are by Osamu Nabeshima, an experienced anime director who’s worked on such projects as Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind, Clamp School Detectives, Devil Man and Mysterious Thief Saint Tail, was involved in character designs for VALIS. Kazuhiro Ochi, Tomokazu Tokoro and Hajime Kamegaki were also production designers. Combined, their works include Six God Combiner Godmars, Fushigi Yuugi, G.I. Joe The Movie, Transformers The Movie, Genesis Survivor Gaiarth and Space Warrior Baldios. These three are mainly animation directors and mecha (mechanized, robot art) designers. Music was also composed by Michiko Naruke and others. Besides the above-mentioned systems, Valis also appeared on the Nintendo Famicom, known abroad as the Nintendo Entertainment System.

The complete release chronology is as follows:

- Valis, MSX (1986)

- Valis, X1 (1986)

- Valis, FM77 (1987)

- Valis, PC9800, (1987)

- Valis, PC8800 (1988)

- Valis, Famicom (1988)

- Valis II, MSX (1989)

- Valis II, X6800 (1989)

- Valis II, PC8800 (1989)

- Valis II, PC9800 (1989)

- Valis II, PC-Engine CD-ROM (1989)

- Valis II, Turbo Grafx-16 CD (1990)

- Valis III, PC-Engine CD-ROM (1990)

- Valis III, Mega Drive (1991)

- Valis III, Turbo Grafx-16 CD (1992)

- Valis, Genesis (1991)

- Valis IV, PC-Engine CD-ROM (1991)

- Valis III, Genesis (1992)

- Valis, PC-Engine Super CD-ROM (1992)

- Super Valis IV, Super Famicom (1992)

- Syd of Valis, Mega Drive (1992)

- Syd of Valis, Genesis (1992)

- Valis Visual Collection, PC-Engine CD-ROM (1992)

- Super Valis IV, SNES (1993)

- Valis X: Yukio: Another Destiny, PC (2006)

Originally published at Japanese Gaming 101.

Recent Comments