For the last decade, gamers have been discussing the ramifications of Sega’s decision to release the 32X as a inexpensive introduction to the 32-bit generation. No one bought it and the Sega brand began its downward spiral. Yep, we all know the story. There’s no sense in beating a dead horse, and I’m sure that if you’re reading this, you most likely have your own mind made up about the darn thing.

Good, because that’s not what we’re here to discuss.

No, not this time. The 32X and its problems are in the books, and any further retro-analysis of the Little-Mushroom-that-Couldn’t wouldn’t really accomplish anything.

But what if I were to tell you that Sega might have had another option? What if there had been a way for them to give gamers a taste of the next generation without having the problems of competing hardware?

Well there might have been, only it vanished almost as soon as it appeared and was practically forgotten.

Virtually the Next Generation

This powerful little microprocessor had its debut and finale in a single game: Virtua Racing. Clocking in at an daunting $100, VR was the most expensive mass-produced domestic Genesis cartridge in history. What made it so expensive was the new chip it featured, known as the SVP (Sega Virtua Processor, not Super Virtual Play, as some erroneously believe) chip, which gave the game the extra muscle it needed to push polygons. It was born during a time of great innovation at Sega, innovation that would ironically eventually lead to the company’s fall from grace.

The SVP chip was first developed as a direct response to the FX chips being used by Nintendo for its SNES. Adding special chips to cartridge games was not a new practice and had been seen in various games on the NES, which used the five MMCs (Memory Management Chip), allowing games abilities not normally supported by the hardware, like split-screen scrolling (Super Mario Bros. 3) and improved battery back-up (Castlevania 3). On the SNES, the two Argonaut-developed FX chips did things that even Nintendo’s new 16-bit console couldn’t do alone. Essentially RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) processors, they functioned in a auxiliary capacity and could render polygons, as seen in Star Fox, or could be used for graphical enhancements, such as sprite stretching and additional parallax scrolling. Most importantly, the FX chips boosted the SNES’s overall performance by lightening its main CPU’s load.

The SVP chip was first developed as a direct response to the FX chips being used by Nintendo for its SNES. Adding special chips to cartridge games was not a new practice and had been seen in various games on the NES, which used the five MMCs (Memory Management Chip), allowing games abilities not normally supported by the hardware, like split-screen scrolling (Super Mario Bros. 3) and improved battery back-up (Castlevania 3). On the SNES, the two Argonaut-developed FX chips did things that even Nintendo’s new 16-bit console couldn’t do alone. Essentially RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) processors, they functioned in a auxiliary capacity and could render polygons, as seen in Star Fox, or could be used for graphical enhancements, such as sprite stretching and additional parallax scrolling. Most importantly, the FX chips boosted the SNES’s overall performance by lightening its main CPU’s load.

These new enhancements made the stock Genesis games of the time begin to look old and stale. Sega quickly began working on a chip of their own that would surpass Nintendo’s. Strangely enough, it had been Sega that had openly criticized Nintendo’s enhancement chips. In an open letter published in the “GF32 Editorial Zone” section of GameFan Magazine in 1994, it publicly lambasted its competitor’s FX technology, while promoting its own 32X upgrade:

Nintendo would like you to believe that by adding chips into their cartridges, they will be saving you money. If Donkey Kong Country, priced at $69.99 is any indication of the money they are saving you, it’s a good thing they are a game company and not your banker. Judging by some of your letters, there are gamers out there who know the gaming industry like the back of their hands. By adding more chips to every cartridge game, Nintendo raises the cost of every cart.

We heard that Nintendo ate some of the initial cost of DKC in order to sell it into the market at $69.99. But what about future titles? Does Nintendo expect to subsidize every title? Also, what does this mean for third party developers and for the size of the game library using the SA1 chip? Can third party developers compete? (Supposedly, Nintendo is offering their add-on chip technology to these developers at such a high cost that it is doubtful you will see anyone else other than Nintendo develop DKC-style titles; Which translates to an extremely limited library for you.)

Strong words, to be sure. One could question Sega’s moral ground for questioning Nintendo’s addition of chips that would raise game prices only to then release the most expensive of all, along with an unsupported add-on.

Regardless of the mixed signals it was sending to gamers, Sega forged ahead with its new project. The resulting technology first appeared in March of 1994, to great fanfare. Contrary to popular belief, the chip was not a Hitachi SH-1 microprocessor, but a Samsung SSP1601 DSP Core. The exact nature of the deal between Sega and Samsung is unknown, but recently unearthed documents have confirmed that they were indeed the manufacturer. You can’t tell by simply looking at the Virtua Racing board, because the chip bears nothing more than the numbers 315-5750. No one knows exactly what differences there were between it and the Hitachi SH-1, but we can at least now dispel the myth of its origin. This misconception is perhaps why most people believed that the SVP was related to the 32X (some have even gone so far as to state that the 32X was an extension of the SVP project). The reality is that the Virtua Processor has more in common with the Sega CD architecture than anything else.

So how exactly does Sega’s chip stack up against the FX twins?

|

SEGA SVP Chip

|

Super FX GSU-1 Chip

|

Super FX GSU-2 Chip

|

|

| Command Chip Type |

Samsung SSP1601 DSP Core

|

RISC

|

RISC

|

| Internal Clock Speed |

23Mhz

|

10.5Mhz

|

21Mhz

|

| MIPS |

25

|

Varies (1.5 stock SNES)

|

Varies (1.5 Stock SNES)

|

| ROM |

1k Instruction

|

16Mbits max (Peripheral)

|

16Mbits max (Peripheral)

|

| RAM |

I-ram 2048 bytes

|

1Mbit (Peripheral)

|

1Mbit (Peripheral)

|

| Memory |

2KB Inst. Cache RAM

|

512 Bytes Inst. Cache

|

512 Bytes Inst. Cache

|

| Internal Data Bus |

16 Bits

|

16 Bits

|

16 Bits

|

| External Data Bus |

16 Bits

|

8 Bits

|

8 Bits

|

| Polygons Per Second |

300-500 ( 16 colors)

|

?

|

?

|

| Sound Expansion |

2 Channels PWM

|

?

|

?

|

What does the above table prove? Well, nothing really, except that the SVP looked pretty powerful on paper. So powerful, in fact, that Sega was planning to use it to test a few of its upcoming arcade ports. Confirmed to have been in line for the SVP treatment were Virtua Fighter and Daytona USA. Of course, only Virtua Racing made it to market, as the other two would be saved for the Saturn’s launch (though Virtua Fighter did appear on the 32X).

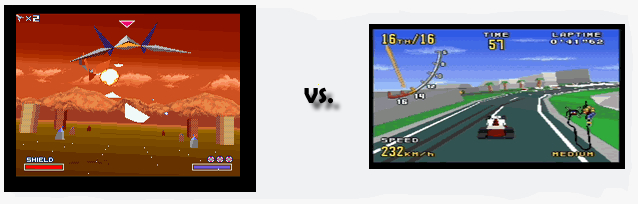

Playing Virtua Racing is the best way to actually see the differences between it and SNES games that use the FX chip for polygon rendering. VR plays smoother due to a higher frame rate, and there’s less break up. Actually, the game plays better than some polygonal racers on much more powerful hardware (I’m talking directly to you, Checkered Flag). The Virtua Processor also had an “Axis Transformation” unit that handled rotation and scaling (basically, the same as the Sega CD).

It did have its limitations, however, which mostly stemmed from the Genesis itself. Unsurprisingly, the same basic issue that plagued the Sega CD and 32X also affected the chip’s potential performance. According to a former Genesis programmer (who wishes to remain anonymous), there were many limitations to the number of colors it could display onscreen. “The primary limitation” he stated, “was that the Genesis graphics hardware used to access the screen could only hold 64k of graphics data, which wasn’t enough to render the whole screen as individual characters. Moreover, the Genesis hardware could only display 512 colors, in 16 color characters, choosing from only 4 color palettes.” Many games used tricks that would allow programmers to switch palettes part of the way through drawing the screen (this is how Sonic the Hedgehog could have a bluish palette underwater coexisting with the brighter colors above) but these kinds of tricks could only do so much.

For more stats and figures on the SVP chip, check out the ongoing documentation project on it at Hacking Cult.

But how did it compare, in reality, to the 32X and Saturn versions? Well, here are some screen shots. You be the judge.

Virtua Racing could hold its own against Star Fox in terms of visuals (though you’ll have to make up your own mind as to which was more fun), and you have to admit that there was a remarkable difference between it and the polygonal games on the Genesis that had come before. The SVP had some serious potential, and if it had been combined with the Sega CD’s hardware features, there’s no telling how much it could have done.

The only real problem was that the chip’s inclusion practically doubled the price of the game, since it was so expensive to produce. In fact, it was so expensive that Sega had to sell it at cost, around 9,800 yen. Additional courses and backup RAM save were nixed to keep the price from ballooning to as much as 14,800 yen. To get around this problem, Sega planned to sell the SVP in a separate cartridge that would work in the same fashion as Galoob’s Game Genie. This way, gamers would only have to purchase the technology once. However, Sega canned the project for unknown reasons and instead chose to focus its efforts on more powerful hardware — namely the 32X. Thus the SVP chip died a quick death, leaving the technology’s untapped potential to fade with time.

A Second Option?

Had Sega put its resources into the SVP instead of the 32X, it may have spared itself from the beating it took at the hands of Sony’s Playstation. Its reputation as a hardware developer was left in tatters after the debacle at the end of the 16-bit era, and most are quick to point to hardware saturation as the chief culprit. It’s no secret that the majority of add-ons fail, and had Sega would have done well to have not released a second for the Genesis. As Trip Hawkins put it in Steven Kent’s book The First Quarter: A 25-Year History of Video Games:

Sega is sending a very confusing message to the customer saying: Buy Genesis; now it’s Game Gear; no, actually it’s Sega CD; no, it’s 32X; forget all of that stuff, it’s Saturn; maybe it’s Titan; how about Pico?” (Kent, 2001, p.481)

Ouch.

It’s therefore arguable that the SVP could have well been a viable alternative. Let’s suppose for a second that the Genesis and Sega CD weren’t discontinued in 1995, and that the 32X was never developed. As a Sega gamer, you were in a pretty good position in 1994. The company was at the top of the market, and its system was receiving massive support from third party developers. The Sega CD was finally getting some decent games with regularity, and Sega had you covered for the next generation with its upcoming Saturn. You only had to hang on to the Genesis for another year at best, before a real upgrade was made available, and Sega would be keeping interest in the Saturn high with a solid line of SVP-compatible titles. If you weren’t interested, you lost nothing, since the stock Genesis would still be supported until the Saturn’s debut. Those with a taste for all things new could dabble in the future by purchasing the enhanced games. No pressure, right?

It’s interesting to think what would have happened had Sega gone through with its original plans for the SVP. Just think about that for a second. Would things have been different? Possibly. I believe that had two important decisions been reversed, the entire face of the gaming industry could have been irrevocably changed:

- Sega’s decision to terminate the SVP program and instead go with the 32X. The most obvious reversal, it essentially means that Sega would have continued to refine and release compatible games using the “piggy back” technique described above. Selling the chip separately would have eliminated the problem of retail cost, as it would only have to be purchased once. Undoubtedly, many gamers would have scoffed at the thought of having to buy a special cartridge just to play SVP-compatible games, but they actually would have been better off. What do you think they would have really preferred to purchase in 1995, with the Saturn on the horizon: the $160 32X or $50 SVP cart? Most of the 32X’s library was really either forgettable or easily done via the SVP, and whatever couldn’t be done could have been shifted to the Saturn to beef up the launch.

- Sega’s decision to move up the Saturn’s launch to May of 1995. Perhaps the biggest blunder of them all, the Saturn parachuted into stores, catching gamers and retailers totally unaware. The botched surprise left the system without a decent launch line up and reduced distribution (Kay Bee Toys was so infuriated that they boycotted the console completely). Had Sega kept on track for the original September date, they could have come to battle with a fully prepared line of games. In the meantime, the Genesis and its SVP titles would have provided gamers with the taste of the next generation they craved, whetting their appetites for the main course. Had additional horsepower been required, Sega could have applied the new technology to the Sega CD, boosting the add-on’s library and adding the chip’s capabilities to its impressive but sorely underused hardware features like biaxial rotation and scaling.

Sad Reality

Sadly, this is all pure speculation, and no one can possibly know if the above combination of steps would have changed anything at all. Still, hindsight sure is fun, isn’t it? I know I’m not the only one that would have preferred SVP-enhanced games to the 32X, which turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. There’s was definitely power in that little chip, and Virtua Racing proved that it could bring the Genesis into the third dimension. Granted, no one was expecting it to crunch massive amounts of polygons, as it was only meant to counter the SNES. Sega saw that the next generation was meant to be battled out by another group of consoles; they just got lost on the way to the fight. The Virtua Processor could have bought them the time they needed to properly prepare by offering gamers a taste of what was to come without straining their wallets. I guess we thus can add another page to the Sega book of What If?

Sadly, this is all pure speculation, and no one can possibly know if the above combination of steps would have changed anything at all. Still, hindsight sure is fun, isn’t it? I know I’m not the only one that would have preferred SVP-enhanced games to the 32X, which turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. There’s was definitely power in that little chip, and Virtua Racing proved that it could bring the Genesis into the third dimension. Granted, no one was expecting it to crunch massive amounts of polygons, as it was only meant to counter the SNES. Sega saw that the next generation was meant to be battled out by another group of consoles; they just got lost on the way to the fight. The Virtua Processor could have bought them the time they needed to properly prepare by offering gamers a taste of what was to come without straining their wallets. I guess we thus can add another page to the Sega book of What If?

Updated: June 2, 2024.

Sources

- “32X Advertising.” The 32X Memorial.

- “Inside Virtua Racing.” David’s Video Game Insanity. December 18, 2004.

- Johnstone, Bob. “Keeping Nintendo Competitive.” HotWired. 1994.

- Lee. “Sega Virtua Processor.” DC Shooters.

- Mcdonald, Charles. “Sega Genesis Hardware Notes.” EmuViews. 2000.

- Pettus, Sam. “Project Mars: Anatomy of a Failure.” SegaBase. 2000.

- “Virtua Racing for MD Version Production Staff Interview.” Beep! Mega Drive. March 1994, 72.

Virtua Racing comparison shots courtesy of Game Pilgrimage.

Pingback: Sega SVP: a curta resposta ao Super FX da Nintendo - Memória BIT

Pingback: VIRTUA RACING – megadrive – VGR2016

How is it “nonsensical” to offer the consumer a $50 cartridge over a $160 add-on that everyone – SOA management and developers included – knew wasn’t anything more than a band-aid? Genesis owners at the time embraced the concept of a lock-on cartridge already with Sonic & Knuckles, so why not build on that? I think it would have done a lot more to conserve the brand name than offering people an expensive add-on when new hardware is around the corner. And I make no mention of “buying the hardware each time.” I clearly state that the cartridge could have been sold separately. For the price of the 32X alone, Genesis owners could have purchased the cartridge and likely two SVP-enhanced games.

As for your argument of the 32X having no effect on Sega as a whole, you’re only thinking of it from the consumer’s perspective. The amount of R&D that went into making the 32X, the internal conflict between SOA and SOJ regarding its design and release, the confusing message sent to developers, and the early Saturn launch combined to hurt Sega going into the 32-bit era. The company was in a poor financial position for having spread itself too thin with too many platforms, while simultaneously discontinuing the one platform that was actually making it money. That’s not ahistorical and has nothing to do with trolls. It’s historical fact. You’re also forgetting that Sega was quite aware Sega CD was not being accepted by 1994, yet it decided to release another add-on anyway. I also think you’re way overestimating the public’s desire for add-ons, and the 32X sales numbers (which you yourself provided) substantiate that.

To be honest, I stopped reading your article before you got to Sega’s SVP program, figuring I’ve read enough like it.

That’s why you should read the whole article. 😉

Your reasoning is truly nonsensical. Sure, Sega would have been smarter to release one add-on with greater functionality, and the dozens of 32X games pale in comparison to the 200 released for Sega CD. Nevertheless, the logic of Sega’s advertisement is both irrefutable and entirely in sync with their overall strategy. The 32X, even for the rapidly-slashed $160 launch price, was a far better deal than Virtua Racing for $100. Indeed, the 32X Virtua Racing Deluxe was noticeably improved over its Genesis counterpart. Add-ons like 32X were both dramatically more powerful and dramatically more cost-effective than the costly chipped cart alternative of buying the same hardware along with the software each and every time. (When adding in the cost of controllers, the advantages of peripherals versus entirely new systems like 3DO becomes even more clear.) There was widespread consumer and press enthusiasm for add-ons in the early- to mid-1990s, and your argument that Sega’s alleged refusal to go with the flow of scamming consumers (or put out games of a lower quality than Virtua Racing, which all Super FX titles were) somehow “tainted” their brand makes sense only to Internet trolls who were not alive at the time. The idea that an item as niche and obscure as 32X–which only 600,000 of 40,000,000 Genesis users ever owned–determined the future of the entire videogame industry and destroyed Sega as a company is profoundly ahistorical.

It’s amazing to me that ad campaigns so unequivocally true as “chipped carts are more expensive than add-ons,” “16-bit arcade graphics,” and “blast processing as a self-described marketing buzzword for Genesis’ faster processor” could be so fanatically demonized while Nintendo’s claims about Project Reality’s (N64’s) “Terminator 2-quality graphics” and Sony’s boasts about PS2 “jacking into The Matrix” with “Toy Story 2-quality graphics” while “rendering individual grains of wood in a door” have received virtually no comment (let alone criticism). It’s extraordinary that Sega CD is reviled for a handful of then-commonplace FMV games while dozens of more obscure systems, from the Fairchild to the Pippin, are forgotten–and Nintendo’s failures (Virtual Boy, N64 DD) are fondly remembered as well-meaning accidents with a few gems. The degree to which Sega is misunderstood and hated, yet simultaneously held to a higher standard than any other company in gaming, is a fascinating phenomenon.