Throughout the eventful and storied history of video games, creators have often taken inspiration from elements of pop culture of the time. As is often the case in many art forms, one work influences another, leaving the public to figure out which parts are wholly original, and which take their cues from other sources. One particular style or artist can influence countless others, who build and expand the art to create entire genres.

Throughout the eventful and storied history of video games, creators have often taken inspiration from elements of pop culture of the time. As is often the case in many art forms, one work influences another, leaving the public to figure out which parts are wholly original, and which take their cues from other sources. One particular style or artist can influence countless others, who build and expand the art to create entire genres.

In video games, this practice has many levels. At its basest form, imagery and other elements are lifted entirely from one source and used in others. Obviously, such blatant plagiarism often draws the ire of the original creators, and rightly so. The hard work of one artist, composer, designer, or programmer should not be so easily inserted into someone else’s product. It diminishes the original and exposes the laziness and lack of creativity of the copier.

On another level, however, close but careful inspiration can create new and wonderful things that ultimately do not share the same space as the source. Imitation, is, after all, the sincerest form of flattery, and some video games have managed to imitate certain elements of popular culture in ways that serve as jump points for new products. Sega was not above this practice, and its funky and futuristic dance game for the Dreamcast, Space Channel 5, pushed this concept to its very limit. As a result, it launched a new franchise, but it also opened the company to legal action relating to the source of the developers’ inspiration.

“No Such Thing as a New Idea”

Certainly, Sega is not the only company that could be accused of taking inspiration for its games from movies and other sources. Game legend Hideo Kojima, who created some of Konami’s greatest hits like Metal Gear and Snatcher, has been quite open about his own influences. He hasn’t shied away from admitting that he was inspired by the works of actors like Robert De Niro and directors such as Ridley Scott. Many fans of the Metal Gear Solid series remain convinced that its version of Solid Snake is based on the hero of John Carpenter’s film Escape from New York, Snake Plisskin, who was played by cinema legend Kurt Russell. Snake’s voice actor, David Hayter, once said that Kojima wanted Russell to voice Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid 4. “I heard that Kojima asked one of the producers on Metal Gear 3 to ask Kurt Russell if he would take over for that game. He didn’t want to do it,” Hayter told Game Informer in 2016.

For the record, Kojima has stated that he did not base Metal Gear’s hero on anyone, arguing that the character originally had no specific direction. “Snake as a character has his roots in the 2D game,” he explained at the 2012 Penny Arcade Expo. “He was a pretty ambiguous character… didn’t have much personality. We wanted to play with that so that’s how he developed.” Though not sourced from any one person, Snake wasn’t entirely original. His bandana was taken from De Niro’s character in Deer Hunter and not Rambo, as many people believe. De Niro was one of Kojima’s favorite actors, and he had watched the movie Taxi Driver daily as a teen. The bandana’s inclusion was a subtle tip of the hat to his idol.

Kojima’s Sega CD classic, Snatcher, also seems to base itself off a movie classic, in this case Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. It was a game that Kojima enjoyed making, but one whose flaws he saw early on. He commented on the story quality a year after Snatcher’s 1992 PC-Engine release and acknowledged the movie’s effect on its design. “I should probably say that compared with other media, Snatcher’s story/setting isn’t very good. We borrowed a lot from Blade Runner. It certainly wouldn’t be strange if someone thought we were just screwing around.”

The thing to keep in mind here is that while Kojima may have taken direct inspiration from existing works, he ultimately created something original. His efforts left enough of the originals to draw a comparison but put enough distance between them to stand on their own as separate pieces. He never saw any repercussions from his efforts, and the games in question are warmly regarded to this day. No one would consider Metal Gear Solid or Snatcher to be copies of Escape from New York or Blade Runner, and no one would think that Kojima should censured for the similarities.

In that regard, Kojima would not be alone since many game designers input elements of their childhood influences and favorite pop culture franchises into their work. Sometimes, however, the influence is a bit too obvious, and the resulting product has landed the developer in legal trouble. Universal City Studios lost its case against Mario Maker Nintendo in 1982, where it alleged that the arcade game Donkey Kong infringed upon King Kong. Universal lost on appeal in 1984, with the court declaring that “The two properties have nothing in common but a gorilla, a captive woman, a male rescuer, and a building scenario.” The case was one of the first major examples of a video game company being sued for taking its inspiration too far and allegedly causing infringement on another company’s property.

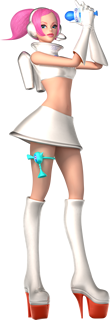

Sega’s Dancing Queen

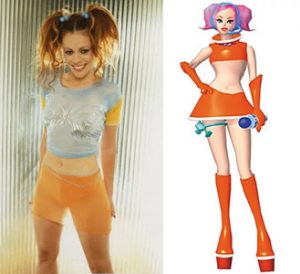

Sometimes, the sense of rights infringement is more personal, with an individual perceiving that their own personal likeness was used in a video game without their permission. Sega found itself in court for just this issue in 2003 due to the similarities the star of its 1999 Dreamcast dance hit Space Channel 5 Ulala had with recording artist Kierin Kirby, also known as Lady Miss Kier of the R&B group Deee-Lite. The group had achieved worldwide fame for its infectious 1990 hit “Groove is in the Heart,” and Kirby’s distinctive look and style was considered one of its major selling points. In videos and onstage, Kirby’s Lad Miss Kier persona performed in knee-high boots and short skirts, and she wore her hair in pink ponytails, much like Ulala later would.

Ulala, who was created by famed game designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi and his team United Game Artists (UGA), does bear more than a passing resemblance to Kirby. It is not known if Mizuguchi ever saw Deee-Lite play or was a fan (his team says it was unaware of the band), but he was definitely a music lover. According to him, the spark that ignited Space Channel 5’s development came directly from aficionados like himself. He had wanted to make a musical game for some time, but Sega’s arcade and console technology thus far had not been up to the task. With its new Dreamcast hardware, he could finally realize his vision. After seeing the musical STOMP, he became more interested in making a console-based rhythm game.

Ulala, who was created by famed game designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi and his team United Game Artists (UGA), does bear more than a passing resemblance to Kirby. It is not known if Mizuguchi ever saw Deee-Lite play or was a fan (his team says it was unaware of the band), but he was definitely a music lover. According to him, the spark that ignited Space Channel 5’s development came directly from aficionados like himself. He had wanted to make a musical game for some time, but Sega’s arcade and console technology thus far had not been up to the task. With its new Dreamcast hardware, he could finally realize his vision. After seeing the musical STOMP, he became more interested in making a console-based rhythm game.

Mizuguchi’s interest was timely, as Sega gave UGA a vague order to develop a title that even casual female gamers would want to play. The demographic was new to him, and he had no idea what kinds of games young girls would want to play. His research into the topic found that most women liked puzzle games, while men sought competition. It would be difficult to create something that appealed to both equally. Mizuguchi felt that men and women viewed female characters quite differently; men tended to judge them based on looks, while women looked more to personality. He also thought that women didn’t want characters that appeared too seductive, as they might be considered rivals.

Mizuguchi decided to move ahead with a rhythm game. Developing for the Dreamcast, he could move beyond the simple, action-centered gameplay of arcades and focus on creating story and character-based projects. With this new title, he could apply his experience from working on coin-ops like Sega Rally and Manx TT to a new platform. He made his pitch to his superiors at Sega of Japan, and Space Channel 5 was born. Mizuguchi explained his vision in a 2016 interview with the website Gaming.Moe.:

“When I think about the games we had at that time, whether they were arcade games or home games, they all fit into neat little compartmentalized genres. But there was a different sort of expression I was searching for. How do I make the player happy? How do I make the people around the player happy, too? With Space Channel 5, I was going in that direction. I wanted the challenge myself and see how many people we could make happy all at one time.”

At first, the main character Ulala looked very different. She was more plain-looking, lacking her signature stylishness. She also had a helmet. The space TV station concept was already established, so the character evolved from there. In a 2016 interview with Coregamers, concept artist, modeler, and animator Jake Kazdal stated that a key source of Ulala’s look was ‘60s sci-fi movie Barbarella, and the team made further changes to the design as development progressed, resulting in her iconic orange and blue dress (the orange color represents the Dreamcast, while the blue is Sega’s corporate color).

Ulala’s finalized look came from Yumiko Miyabe, who also designed the Morolian invaders and other characters. Miyabe could have been considered something of a Sega legend in her own right. Her résumé included some art design on some of the Saturn’s greatest titles, like NiGHTS into Dreams, Clockwork Knight, and Panzer Dragoon Saga. She came up with some initial designs for Ulala, and her work garnered her a position as the game’s art director. Takashi Yuda, best known for having created Knuckles the Echidna, became the project’s director. He took Miyabe’s and Mizuguchi’s designs and developed the concept of a space TV station where a reporter fought back an invasion of dancing aliens (named Morolians after UGA artist Mayumi Moro) using kicks and laser guns. Mizuguchi wasn’t too excited with the character using such typical weapons, calling it “too cool and stylish,” and he insisted on a game that played like a musical. During the discussion with the development team, which had started with 10 people but since ballooned to 24, Mizuguchi was told that the design simply wasn’t heading the way he intended.

To illustrate his vision, Mizuguchi resorted to making the team attend a six-month comedy workshop. Attendance was mandatory, and they spent hours learning the psychology of laughter. Mizuguchi spent just as much time on Ulala’s character design, and her CG model was redrawn several times to make her friendlier and less sexy. Her personality was tweaked as well, and she became more of a casual spirit. Gone were the kicks and gunshots, replaced now by slick dance moves. For Space Channel 5’s western release, Ulala’s model was altered once more to make her a bit different in appearance from the Japanese version, likely a reflection of different cultural views towards women.

Space Channel 5 debuted on the Dreamcast in December 1999 in Japan and the following year in the U.S. and Europe. Sega of America made its release a major celebration, creating a special show at E3 to hype the gameplay and visuals. The inclusion of pop icon Michael Jackson – the result of him seeing an almost-complete version during one of his frequent visits to Sega of America and wanting to join in – also created a buzz around the game. Along with other original titles like Jet Grind Radio, Space Channel 5 brought a special level of creative quirkiness to the Dreamcast that has made the console a fan-favorite in the years since its official retirement. It also caught the attention of Miss Lady Kier.

Miss Lady Kier vs. Ulala

With so many people contributing to the creation of Space Channel 5’s main character, it would seem unlikely that anyone would contest the source of her design. But in April 2003, Kierin Kirby’s accusation did exactly that. The singer filed a lawsuit against Sega, Agetec, and THQ Inc. (Agetec released a special edition of the game for the PlayStation 2, and THQ was behind the Gameboy Advance version). She argued that Ulala was entirely based off her look and style. The $750,000 suit alleged causes of action on six counts: (1) common law infringement of the right of publicity; (2) misappropriation of likeness; (3) violation of the Lanham Act (the main federal trademark statute of law in the U.S.); (4) unfair competition; (5) interference with prospective business advantage; and (6) unjust enrichment. Kirby believed that Sega had used her name and likeness illegally in its development and marketing of Space Channel 5, particularly concerning Ulala.

Kirby, who was the lead singer of Deee-Lite from 1986 to around 1995, is also a fashion designer, artist, and choreographer. She left her home town of Youngstown, Ohio at 19 to pursue a career in fashion design. In her case against Sega, Kirby claimed that for her Miss Lady Kier persona, she had developed a “specific, distinctive look of a fashionable, provocative, and funky diva-like artistic character.” The identity was unique and combined retro and futuristic elements into a singular style. According to Kirby, her signature look included things like platform shoes, knee socks, and red or pink hair worn in pigtails and other styles. Moreover, she alleged that the very word “ulala” was part of that identity, as she frequently used it while performing and said it in “Groove is in the Heart” and three other songs. For Kirby, all these aspects combined to create a persona and likeness that was distinctively hers.

Kirby also cited Sega’s attempt to recruit her to promote Space Channel 5 as evidence that Ulala was based on her. The advertising firm PD*3 Tully Co. contacted her in July 2000 on behalf of Sega as part of the promotional buildup to the game’s British release. Several Deee-Lite songs were under consideration for use in advertising, including “Groove is in the Heart.” According to Kirby, Tully offered her $16,000 to promote Space Channel 5 in England and possibly Europe. She declined.

The fallout from Kirby’s accusations would extend well beyond Sega. At the center of her case was whether celebrities had a claim to their public personas. For many, their likeness and persona are commodities to be managed and capitalized upon. Morgan Freeman’s iconic voice or Jack Nicholson’s smile and mannerisms, for example, are traits that are inherently tied to those artists. It is only natural that they would seek to protect any unauthorized uses that could affect their overall value as celebrities. The issue was whether Ulala represented such a threat to Kirby and if so, in what manner.

Sega countered Kirby’s allegations by arguing that Space Channel 5 had been in development since 1997 in Japan, long before it contacted her. Additionally, Sega contended that the First Amendment protected its right to free expression and gave it a complete defense against Kirby’s claims. It also emphasized Space Channel 5’s Japanese origins. UGA developers said they had never heard of Kirby, and when Yuda testified in court, he explained that the main character had initially been male but had been changed to comply with Sega’s mandate of creating a female-oriented game. Yuda also stated that Ulala had large anime influences, and that her name was a derivation of the Japanese name “Urara” and was changed to make pronunciation easier for English speakers.

As far as Sega was concerned, Ulala was in no way imitating Kirby, since her dancing was also the result of UGA’s design. Nahoko Nezu, a dancer and choreographer, was responsible for Ulala’s dance routines and created them at Yuda’s direction. Yuda videotaped her dancing so that he could later implement it into the game. Nezu claimed her moves were hers alone, and that she also did not know who Kirby was. Also, none of Kirby or Deee-Lite’s music was used, nor were any of the musical tracks based on or references to their work. Ken Woodman’s 1966 instrumental song “Mexican Flyer,” was the main theme used in Space Channel 5. Woodman himself was a bit surprised at UGA’s request, not expecting anyone to be interested in using his music for a video game. “When we approached [Woodman] about the soundtrack,” Mizuguchi had said about their meeting, “he was really surprised that somebody wanted to use his music, more than thirty years later.” The rest of the score was done by Sega’s in-house composers, Naofumi Hataya and Kenichi Tokoi. Woodman died in November 2000, only a month after Space Channel 5’s European release and at least had the satisfaction of seeing a new generation discover his classic song.

Sega also argued that Kirby’s claims were negated by the statute of limitations. For their part, Agetec and THQ contended that Kirby had no right due to the defense of laches, which asserts that “a legal right or claim will not be enforced or allowed if a long delay in asserting the right or claim has prejudiced the adverse party.” In other words, Kirby had simply waited too long to make her case and no longer had any right. The court did not accept the publishers’ arguments and instead made its decision based on the allegation of infringement.

Ultimately, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge James C. Chalfant ruled in the defendants’ favor, citing several key differences between Ulala and Kirby. First, the physique of Sega’s character was much taller and slender than Kirby’s. Additionally, Ulala wore variations of the same outfit during the whole game, while Kirby admitted to having no singular identity. According to the Deee-Lite singer, the styles she used were “continually moving” and she was “not the type of artist that wants to do the same thing every time.” The settings involved were also different. Space Channel 5 took place in the future in outer space, while Kirby’s style was 1960s retro. Moreover, none of Kirby’s videos or photographs related to outer space in any way. Chalfant explained that combined, these differences were enough to prove that Ulala was transformative. That is to say, she represented a transformation of the original work that added new expression or meaning and new aesthetics.

The loss was a costly one for Kirby. California civil code required unsuccessful plaintiffs to pay the defendant’s legal fees, which in this case amounted to a staggering $763,000 (ironically a larger sum than Kirby had sought). The court reduced the amount to $608,000. Kirby appealed the decision but lost in September 2006. Justice Paul Boland, though ruling in Sega’s favor, noted that Ulala did bear some similarities to Kirby’s Miss Lady Kier character. “Ulala’s facial features, her clothing, hair color and style, and use of certain catch phrases are sufficiently reminiscent enough of Kirby’s features and personal style to suggest imitation,” he wrote. Boland also recognized that Sega’s attempt to recruit Kirby to market and promote Space Channel 5 in 2000 was evidence that the company was aware of her and considered an association with her to be beneficial to the game’s sales in Europe.

Despite this connection, Boland, much like Judge Chalfant, also decided that there were significant differences between Ulala and Kirby. He contended that Sega didn’t merely imitate Kirby; it “added expression” to create something transformative. Kirby was not satisfied with this argument, stating that Sega could not hide behind the First Amendment because the character of Ulala said nothing “factual or critical or comedic about a public figure.” Boland countered this allegation by noting that adding new expression or meaning to a character is enough to make it transformative, and that no new meaning or message was needed. In other words, Ulala was not required to identify with or convey any message about anyone. Even if she were indeed based on Kirby, the fact that Sega placed her in a different location and time and made alterations to her appearance was enough to make her transformative. “The Ulala character satisfies this test,” he concluded.

Sega Sets the Standard

The California Superior Court’s decision, upheld on appeal, had major consequences regarding how far celebrities could go to protect their likenesses within the state. Sega’s victory made it much harder for a case for misappropriation of likeness to be won due to the broader protections offered by California’s constitution. The fact that state’s civil code awards entitlement to legal fees and costs to the prevailing party, including appeals, also makes losing such a case a costly exercise. Considering that a large amount of game development is done in California, the ramifications of the decision were huge.

To clarify, though Kirby v. Sega of America Inc. was a landmark case for video gaming, it was not the first example of California’s Supreme Court taking on the issue of celebrity rights of publicity. In 2001, it had ruled that celebrity lithographer Gary Saderup had infringed upon the rights of publicity of Comedy III Productions, an entertainment and licensing company founded in 1959 by the comedy act The Three Stooges, by selling t-shirts with drawings of the famous trio. Comedy III owned the Three Stooges “deceased rights of publicity,” which mandated that consent from the holder must be issued before the deceased’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness could be used for commercial gain. Saderup’s defense was that his t-shirts were artistic and protected under the First Amendment, an argument the court did not accept because the shirts did not add anything new to the original and derived their appeal “primarily from the fame of the celebrity depicted.” This context was different from other artistic uses of property, such as artist Andy Warhol’s silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. According to the court, those works “went beyond the commercial exploitation of celebrity images and became a form of ironic social comment on the dehumanization of celebrity itself.”

The court also cited Winter v. DC Comics, where the singing duo Johnny and Edgar Winter sued comic publisher DC in 2003 over characters in the comic Jonah Hex. In it, Hex battled a pair of half-snake, half-human killers called the Autumn Brothers. The characters were named Johnny and Edgar, and they had fair skin and long, white hair, similar to the Winters. The Winters alleged a misappropriation of their rights of publicity because the characters were “based” on the them. DC defended itself on First Amendment grounds and won. The case went to appeal, which DC also won, and the Winters took it all the way to the California Supreme Court. DC scored another victory when the court decided that the Autumn Brothers were sufficiently transformative to not constitute infringement.

Both Comedy III and Winter served as the foundation for Kirby, leading to the first major case of celebrity publicity rights involving video games. An avalanche of similar lawsuits would follow, including the rock band No Doubt suing publisher Activision in 2011 for letting players manipulate depictions of them in Band Hero, and actress Lindsay Lohan suing Rockstar Games in 2014 over the character Lacey Jonas in Grand Theft Auto IV. These cases, while falling on different places on the spectrum of what was considered infringement and what wasn’t, all owe their results to the Kirby case. No Doubt won its lawsuit because the avatars in Band Hero played and acted just like their real-life counterparts; there was nothing transformative about them. On the other end of the spectrum, Rockstar prevailed against Lohan on appeal in March 2018, with the court deciding that Jonas in Grand Theft Auto IV was not a direct copy of her because “artistic renderings are indistinct, satirical representations of the style, look, and persona of a modern, beach-going young woman that are not reasonably identifiable as plaintiff.”

Kirby v. Sega of America Inc. served as a pillar for both of these cases, marking the first clear example of video games being used to set a legal precedent in this manner. It has since served as a balancing test for courts to weigh a celebrity’s publicity rights against the protected, expressive content that spurred the legal action in the first place. For instance, a California federal district court cited Kirby v. Sega of America Inc. when deciding the case of former Arizona State University quarterback Sam Keller, who sued Electronic Arts and the NCAA over use of his likeness, stats, and jersey number in the game NCAA Football 2009. The court ruled in Keller’s favor because the game did not pass the transformative use test. A similar conflict in 2015 involving the NCAA and UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon concluded in the athlete’s favor. Cases continue to appear, such as the 2014 fight between former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega and Activision over a similar character, which ended in victory for Activision based on the transformative use test.

Strong Signal from Spaceport 9

Kirby and Sega appeared to have patched things up in later years, with Deee-Lite’s song “Groove is in the Heart” appearing in the Nintendo Wii version of Samba de Amigo, coincidentally during a stage that featured Ulala. The character continues to appear in Sega games, and no further action has been taken by Kirby. The issue is still an understandably touchy one for the artist, as evidenced by her back-and-forth with the enthusiast site Segabits on Twitter in 2012. It is unknown how much, if any of the sum Kirby was ordered to reimburse Sega has been paid, and she continues to sing and DJ to this day.

The biggest takeaway from the Kirby case is that there is no universal law, at the state or federal level, that protects a person’s likeness and persona in all situations. The transformative use test is invoked on a case-by-case basis. Sega may not have intended or even known how far-reaching the outcome of its victory would be, but the company has earned a place in video game history by setting the precedent by which such contests will be judged. It’s unlikely that Mizuguchi, Yuda, and Miyabe ever thought their creation would cause such a stir, and most of those who play Space Channel 5 are probably unaware of the controversy surrounding the game. Hopefully, Ulala’s future will be free from further legal action, and she will be able to dance her heart out, to the “Deee-Lite” of Sega fans everywhere.

Sources

- Cifaldi, Frank. “E3 Report. The Path to Creating AAA Games.” Gamasutra. 20 May 2005.

- “Kirby v. Sega of America Inc.” Court of Appeal, Second District, Division 8. 25 Sept. 2006.

- “Jake Kazdal: An American Gaijin.” Coregamers. 08 Sept. 2016.

- Farber, Eric. “U-La-La, What’s Happened to Our California Rights of Publicity?” Chapman Law Review 11:449, 2008: 449-464.

- Frederiksen, Eric. “Kurt Russell Was Almost the Voice of Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid 3.” Technobuffalo. 28 Mar. 2016.

- Gamespot Staff. “Sega’s Tetsuya Mizuguchi Interviewed.” Gamespot. 3 Dec. 2001.

- Gardner, Eriq. “No Doubt, Activision Settle Lawsuit Over Avatars in ‘Band Hero.'” Hollywood Reporter. 3 Oct. 2012.

- Goroff, Michael. “Lindsay Lohan’s GTA V Legal Battle Is Finally Over.” EGM. 30 Mar. 2018.

- “Hideo Kojima Talks Snatcher.” 1993. Shmuplations.

- IGN Staff. “IGNDC Interview Space Channel 5’s Tetsuya Mizuguchi.” IGN. 19 May 2000.

- Justice, Brandon and Williamson, Colin. “IGNDC Sits Down with Space Channel 5’s Tetsuya Mizuguchi.” IGN. 6 Oct. 1999.

- Kemps, Heidi. “Interview: Tetsuya Mizuguchi of Enhance Games.” Gaming.Moe. 31 Mar. 2016.

- Kojima, Hideo. “Kojima Dreams of Blade Runner.” Rolling Stone. 20 Oct. 2019.

- Krotoski, Aleks. “Interview with Tetsuya Mizuguchi.” Guardian. 7 Feb. 2007.

- “Lady Miss Kier’ Hammered with Opponent’s Attorney’s Fees.” Legal Reader. 25 Sept. 2006.

- Leichtman, David, Hazzard, Yakub, Martinez, David and Paul, Jordan S. “Transformative Use Comes of Age in Right of Publicity Litigation.” Landslide. Sept./Oct. 2011.

- Linshi, Jack. “Judge Dismisses Manuel Noriega’s Call of Duty Lawsuit.” Time. 28 Oct. 2014.

- Lynch, Casey. “PAX: Solid Snake Wasn’t Based on Snake Plissken.” IGN. 1 Sept.

- Matulef, Jeffrey. “Lindsay Lohan’s Grand Theft Auto Lawsuit Rules in Rockstar’s Favour.” Eurogamer. 9 Jan. 2016.

- Metropolitan News Staff. “Game Maker May Use Celebrity’s Likeness if ‘New Expression’ Added—C.A.” Metnews. 26 Sept. 2006.

- Moosavi, Amir. “In the Realm of the Senses: Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s Synthesis of Synaesthesia & Video Gaming.” Medium. 15 Dec. 2015.

- Niizumi, Hirohiko. “Mizuguchi headlines TIGRAF fest in Tokyo.” Gamespot. 11 Nov. 2003.

- “The SEGA Five: 5 Year Anniversary Special.” SEGAbits. 6 Feb. 2015.

- Sholder, Scott J. “Video Game Cases May Break New Right of Publicity Ground.” Cowan, DeBaets, Abrahams & Sheppard LLP. 1 Aug. 2014.

- Sparrow, Andrew. The Law of Virtual Worlds and Internet Social Networks. New York, NY: Routledge.

- “Supreme Court Rules Three Stooges T-shirts Are Not Protected Art.” Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. 2 May 2001.

- “Tribeca Game Show Hideo Kojima.” YouTube, uploaded by The Gamer Liquid. 3 May 2017.

- Welte, Jim. “Deee-Lite Singer Loses Sega Lawsuit.” Gamespot. 28 Sept. 2006.

- Wheatley-Liss, Deidre R. “Doctrine of Laches Means You Are ‘Out of Time’.” LexisNexis Legal Newsroom: Estate and Elder Law. 26 Jan. 2012.