People often have distinctive opinions about what constitutes a true gaming classic. The term tends to get tossed around rather indiscriminately, with nostalgia often serving as the primary factor for many. After all, a great game is forever associated with a particular time and place in many gamers’ lives, and as time goes by and they get older, they tend to tighten their grips on those precious memories. Great games can be considered classics, to be sure, but it’s mostly those particular titles that redefine their genres or the game creation process as a whole that are most deserving of the title. Those games that are remembered for their contribution to the industry as well as for the great experiences they provided are the ones that will endure in the minds of gamers of all ages.

People often have distinctive opinions about what constitutes a true gaming classic. The term tends to get tossed around rather indiscriminately, with nostalgia often serving as the primary factor for many. After all, a great game is forever associated with a particular time and place in many gamers’ lives, and as time goes by and they get older, they tend to tighten their grips on those precious memories. Great games can be considered classics, to be sure, but it’s mostly those particular titles that redefine their genres or the game creation process as a whole that are most deserving of the title. Those games that are remembered for their contribution to the industry as well as for the great experiences they provided are the ones that will endure in the minds of gamers of all ages.

Among the many great games in the Genesis library, there are a small number of titles that fit that specific description. Even fewer set the bar so far above the competition that they become a clear and irrefutable example of the true power of a gaming console. However, one towers above them all, given the amazing circumstances of its development and the incredible combination of talent that came together to make it a reality.

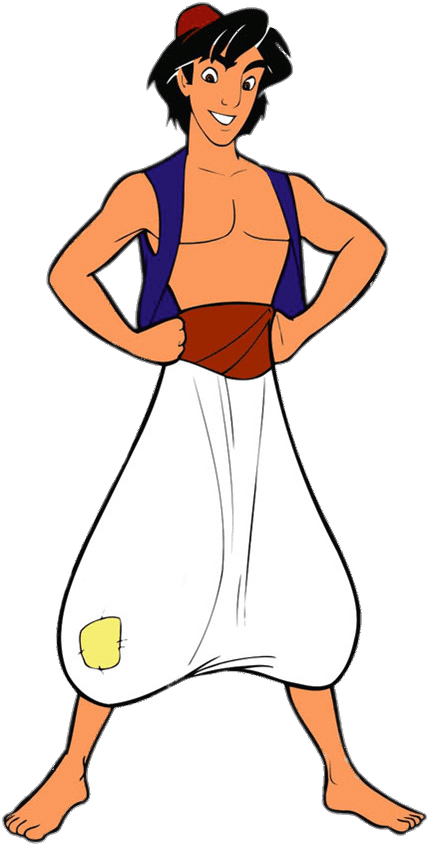

That game is Disney’s Aladdin.

Changing developers and invoking the direct involvement of Disney’s top animators, Aladdin proved to the world that video games were capable of going beyond being fun. It showed that they could recreate the cinematic experience in ways that no one believed was possible.

Grey Clouds at BlueSky

Genesis gamers are quick to recall the Virgin Games release of Aladdin whenever the name arises in conversation, but few people know that the game actually began life at Sega as a BlueSky Software project. Under Sega’s license with Disney titles, Aladdin was in quiet development under a team of around eight people. The film was already in theaters, and Sega’s title needed to quickly capitalize on its growing popularity. Former BlueSky Artist Tom Moon explained to Sega-16 what it was like to be involved with such a high profile project, especially after coming off of The Little Mermaid, another licensed Disney title. “I do remember feeling a lot of pressure to do well on the Aladdin game, but that was more of a personal thing. I was impressed that BlueSky was able to capture such clients such as Disney and Spielberg, and being new to the company and the industry, I wanted to do well and establish myself as a person worthy of the team.”

Sega had won the Aladdin license due to its great track record with Disney properties on the Genesis. The two creative powerhouses had a history that went back several years, and their working relationship was quite solid. Hits such as Quackshot and Castle of Illusion on the Genesis, as well as several quality conversions on the Master System and Game Gear, had convinced Disney that the company could be trusted to create quality games with its licenses. Similarly, Capcom had a stellar history with Disney licenses on Nintendo consoles, specifically during its terrific run on the NES with such favorites as Ducktales and Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers. Both companies easily won the rights to the latest animated feature film, and given its history of quality releases, Disney had no reason to think that Sega wouldn’t produce another hit.

Sega had won the Aladdin license due to its great track record with Disney properties on the Genesis. The two creative powerhouses had a history that went back several years, and their working relationship was quite solid. Hits such as Quackshot and Castle of Illusion on the Genesis, as well as several quality conversions on the Master System and Game Gear, had convinced Disney that the company could be trusted to create quality games with its licenses. Similarly, Capcom had a stellar history with Disney licenses on Nintendo consoles, specifically during its terrific run on the NES with such favorites as Ducktales and Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers. Both companies easily won the rights to the latest animated feature film, and given its history of quality releases, Disney had no reason to think that Sega wouldn’t produce another hit.

Sega had the Aladdin license for both the Genesis and Game Gear, and its game was to directly compete with Capcom’s SNES version, yet despite the efforts of the experienced BlueSky staff, things were not looking well. The problem came from the fact that Aladdin was not BlueSky’s primary project. The team was hard at work on Jurassic Park, which was almost guaranteed to be a merchandising juggernaut. Sega had the license to the franchise and was eager to get a title onto store shelves. Priority was given to the game over Aladdin (the development team was three times as large and included people also working on Aladdin), so progress on the Disney title was slow in coming. Moon recalled the team being in high spirits during development, in spite of the amount of work they faced. “I remember that every day when I went into the office, (BlueSky producer) Mark Dobratz would fire up the soundtrack to Aladdin to get us in the spirit. We all loved the movie, which is why Mark and I were excited to do the game.”

Even with the high morale at BlueSky and the hard work being done, the project quickly began to lose the race against Capcom. Disney Producer Patrick Gilmore had seen both the SNES and Genesis versions of Aladdin and was not happy with the progress Sega was making. He felt the art was bland, and while the overall game was solid, it did not break the mold of the typical licensed platformer. Gilmore was looking for something better, and there were concerns at Disney about the project’s progress. The game was still early in development, and BlueSky had just started working on character animations and level design.

No one at BlueSky seemed to notice Disney’s increased attention to its licenses or the need for a higher level of quality than had been previously accepted. The group worked diligently, but there was never an overriding sense of urgency to the project. BlueSky management never indicated that Aladdin was any different from the other Disney titles that had preceded it, and no pressure was put on the team to give the game priority. Jurassic Park got the lion’s share of attention, and as a result, Aladdin suffered. Moon worked on both games (he did the waterfall level on Jurassic Park) and said that both he and his colleagues were eager to impress on all projects equally, but all eyes were on Isla Nublar. “No one from management came to us and said anything like, “Hey guys, this is DISNEY we are talking about,” he admitted. “This is our big chance. We’d better ACE this project or else!”

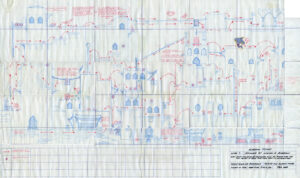

One of the principle issues with BlueSky’s adaptation was that it did not capture the natural and intuitive visual style of the film. Each Disney film has a particular style and shape language that is the product of the directors, art directors, layout designers, and supervising animators all working together. For Aladdin, much of the art direction came from caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, who was present during the design phase and collaborated with the feature animation team. His influence is notable in the work of Eric Goldberg, lead animator for the Genie. Hirschfeld also influenced the curvilinear style of the many of the film’s characters and locations, such as Agrabah and the Sultan’s castle. There was a major effort on the part of the design team to avoid the use of parallel lines, and locations became rounded and wind-swept. This was completely absent from the BlueSky version, which was instead straight and parallel. Creating the distinctive aesthetic of the movie was quite difficult in a tile-based video game, and the art direction not heading the way Disney wanted. “I felt growing pressure that the game was not reflecting the inspiring production design of the film,” Gilmore told Sega-16 via email. For these reasons, Disney management felt it was better to stop the project while only a single, semi-completed level had been started.

Ironically, it wasn’t alone in its intentions. Jesse Taylor, the Sega producer on Aladdin, was fighting to balance the two major licenses among Bluesky’s other projects, and he knew that it would be difficult for his smaller team to maintain the overall level of quality. Former BlueSky Art Director Dana Christianson believes that Taylor decided to go with Jurassic Park so that the company’s best efforts would be focused on only a single major release. “He had us working on Jurassic Park and something else,” Christianson told Sega-16, “and he probably didn’t want all of those eggs in one basket. It (Aladdin) was sort of secondary to Jurassic Park, and they (Sega) were probably smart to see that.”

In truth, Sega had neither the resources nor the financial need to develop two major licensed titles simultaneously. Former Genesis Group Marketing Director Diane Fornasier specified to Sega-16 how Jurassic Park was given priority status. “It is very true that we placed a great deal of pressure on them (BlueSky) for the Jurassic Park game that came out in summer 1993, so it is very reasonable that we would not want them to do the next important game of the year as well. In the beginning of 1993, we had a strategic planning meeting to lay out the entire 1994 fiscal year line of ‘million sellers,’ and Jurassic Park was the designated game for summer 1993, followed by Aladdin in fall 1993 and Sonic Spinball in holiday 1993.” Sega’s fiscal year ran from April to March, and with Jurassic Park launching first, it was to spearhead the publisher’s all-important holiday push. Theoretically, Aladdin could very well have been completed by its designated launch date. However, not having BlueSky’s entire attention would most likely have been reflected in the final product. Moon hypothesized about the potential for a completed game. “My guess would be that after finishing up Jurassic Park, BlueSky would have poured a lot of their resources into the Aladdin game in order to ‘catch up’ on the development. The deadline would have been tight, but not impossibly so.”

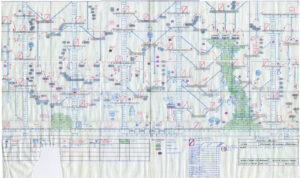

Disney was not ready to let its latest animated hit to take a back seat to another property, and it wasn’t very happy that Aladdin wasn’t getting the attention it needed. Gilmore recommended bolder action be taken regarding the license, and he shopped around for another alternative as it became increasingly clear that management was going to pull the plug. The game was soon canceled, and BlueSky continued focusing on Jurassic Park, which launched to great sales and acclaim. Interestingly enough, that game contains the only released evidence on the Genesis that there was a BlueSky Aladdin in development. Included as an Easter egg by the artists, Jurassic Park’s in-game map contains an upside-down Genie’s lamp disguised as a mountain range on the island’s northwestern coast.

With the BlueSky version of Aladdin canceled, Disney, for the moment, was left with a hit movie in theaters and no game to go with it. Though it may seem like this worked to the studio’s detriment, it was largely done by design. It was the perfect opportunity for Disney to free itself of the risk that always went with licensing its properties to other publishers and to take a more active role in game development.

Disney Expands

In all fairness, the work BlueSky had done on Aladdin was not considered by anyone at Disney to be poor in quality. Many of those involved thought the project was shaping up to be a competent platformer. The problem was that Disney was looking for something far beyond mere competence. It wanted the game to propel the player into the movie and feel like a continuation of the adventure rather than just another licensed product. For Disney, BlueSky’s version did not satisfy those needs in a number of areas, including art and animation.

BlueSky’s Aladdin wasn’t an example of a developer producing a disappointing product, but more of watershed moment for Disney that convinced management that the company needed to make some changes in its own policies. For some time, Disney Feature Animation was weighing the decision of taking a more active role in bringing its film catalog to video game consoles. To this point, the company had always licensed its characters to developers, and while mostly successful, this tactic always presented an element of risk. Few felt that an outside group could accurately portray Disney’s stable of lovable heroes and heroines, and there was always something that was seemed to be off about many of the games released. It was enough to stir the House of Mouse to consider developing games on its own, and the only problem was that Disney had no idea how to go about it.

In order to full appreciate the magnitude of this decision, one must consider what was at stake for Disney. With a catalog of properties and characters unmatched in the film industry, it was vital that the studio maintain strict control over its integrity and quality. Films like Snow White and Cinderella represented the lifeblood of Disney, with generations of fans the world over coming to the parks and buying merchandise. Damaging a franchise would hurt the corporation as a whole, far beyond any single fiscal quarter. It would mean that the trust of the fans, the trust that Disney would safeguard cherished childhood friends, would be violated. That kind of betrayal would be catastrophic to a company like Disney.

A good example of a major gap in quality between film and game is 1991’s Fantasia, which was developed by Infogrames but was ironically published by Sega itself. Rushed through production, the game played horribly and failed to capture any of the magic that defined the Oscar-winning film. The side-scrolling platformer was not even competent on its own, and the attachment of one of Disney’s most famous licenses made the failure sting that much more. Former Sega of America Head of Product Development Ken Balthaser recognized Fantasia’s incredible shortcomings in our 2006 interview. “That game nearly cost us dearly;” he conceded, “there was so much pressure on me and on the team, that unfortunately, I made the call to release it even though the gameplay wasn’t ready. I truly wish I hadn’t, but sometimes you have to make those decisions. You need games in the pipeline, especially big licenses, but the game was just simply unplayable.” Reportedly, Disney was not aware that Sega had been erroneously awarded a license for the game, as Fantasia was a beloved project of Walt Disney and was not to be handled outside the company. Disney cleared up the confusion with a deal that was beneficial for Sega (though the game was recalled and destroyed, and reportedly only around 5,000 copies survived). In return, the game-maker was able to compensate for Fantasia’s shortcomings with the excellent Quackshot and World of Illusion, as well as a string of well-received Game Gear releases.

A good example of a major gap in quality between film and game is 1991’s Fantasia, which was developed by Infogrames but was ironically published by Sega itself. Rushed through production, the game played horribly and failed to capture any of the magic that defined the Oscar-winning film. The side-scrolling platformer was not even competent on its own, and the attachment of one of Disney’s most famous licenses made the failure sting that much more. Former Sega of America Head of Product Development Ken Balthaser recognized Fantasia’s incredible shortcomings in our 2006 interview. “That game nearly cost us dearly;” he conceded, “there was so much pressure on me and on the team, that unfortunately, I made the call to release it even though the gameplay wasn’t ready. I truly wish I hadn’t, but sometimes you have to make those decisions. You need games in the pipeline, especially big licenses, but the game was just simply unplayable.” Reportedly, Disney was not aware that Sega had been erroneously awarded a license for the game, as Fantasia was a beloved project of Walt Disney and was not to be handled outside the company. Disney cleared up the confusion with a deal that was beneficial for Sega (though the game was recalled and destroyed, and reportedly only around 5,000 copies survived). In return, the game-maker was able to compensate for Fantasia’s shortcomings with the excellent Quackshot and World of Illusion, as well as a string of well-received Game Gear releases.

Before condemning anyone, one must realize that such a scenario was not entirely the fault of the developers. In truth, many elements worked against them by the time the license was secured. Disney Feature Animation was very possessive of its materials, often not sharing enough with game designers and programmers to give them what they needed. By the time developers were able to pry away the details about a particular film, the creative window was significantly shortened. Second, company deadlines left little room for refinement, and many products (like Fantasia) ended up being rushed to market.

This was the type of situation that Disney wanted to prevent. With all art development for licensed games being handled by the licensees, there was no way for its representatives to manage the design process and ensure quality control. Studio management could have simply tiered its licensing, giving more access only to those developers that created the highest quality software with its properties, but this still did not resolve the issue of participation. With the best animators in the world on its payroll, Disney felt that it should have a greater presence in the actual creation of specific elements of game design, such as character animation and art. What was needed was a partner that had the design and programming talent to help it transition its legendary history onto game consoles, as well as the technology to do that history justice. The problem was that there was no publisher in the video game industry that met that standard.

Except for one…

It All Started with Rollerblading Dinosaurs

As a producer for Disney, Patrick Gilmore found himself in a unique position regarding licenses. He was able to talk to different development teams and see how each one worked, giving him much-needed information for choosing the right one to handle a specific property. As it turns out, Aladdin was one license that kind of fell right into his lap. “I volunteered to be the sole licensing producer,” he told Sega-16 via email, “taking all the unwanted projects from the other producers. The tradeoff was that I would get a promotion from assistant producer to associate. My boss went for it, and I took over all those projects. One of the projects was Aladdin.”

In reality, Virgin Games’ selection as the developer for Aladdin was not something planned from the start, and it took a combination of several events to make it happen. The seeds of the deal that would put Disney’s 31st animated classic on the Genesis run back all the way to the 1992 Consumer Electronics Show (CES). It was there that Gilmore met Virgin Games Design Director David Bishop, who showed him Global Gladiators. “THAT is the game that blew me away.” Gilmore commented to us. “It had beautiful backgrounds, awesome animation, modern music, and a fidelity and precision to the gameplay that very, very few people in the U.S. were capable of.”

To this point, Virgin Games and Disney had only agreed on a licensed game for the Jungle Book film, and the two companies were looking for further ways to work together. At CES, Bishop approached Gilmore, along with Virgin Vice President of Product Development Dr. Stephen Clarke-Wilson and showed him a game demo by Bill Kroyer. Kroyer was a former Disney animator who had directed the animated film Ferngully: The Last Rainforest, and he had created a demo for a game using a license called DynoBlaze, which went through several forms but was never released. Conceived as competition to the immensely popular Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, DynoBlaze featured a quartet of rollerblading dinosaurs that fought off enemies with hockey sticks. Still very early on, DynoBlaze was barely playable. “It was never really a game,” Clarke-Wilson clarified to Sega-16, “but more of a concept of dinosaur kids on roller blades. Once we got busy with these big licenses, it basically fell by the wayside.”

Gilmore was impressed by the demo and requested that he let them shop it around at Disney. Shortly thereafter, Clarke-Wilson got a phone call to send someone over to talk about a possible license. “David Bishop went up to Disney and under strict NDA saw a rough cut of Aladdin, “he detailed, “and we were pitched the idea of quickly making an Aladdin game using Disney animation and all of the tools and processes we had evolved at Virgin since 1991.” Gilmore’s superiors were impressed with Virgin’s high regard for Disney’s animated features, as well as the progress it had made on Jungle Book. Virgin now had the attention of the most powerful animation house in the world and a chance at not only adapting a major hit film, but of also establishing a continuous relationship with one of the most sought-after licenses holders of all time.

Bishop was tasked with coming up with a proof of concept that could be used to convince Disney to give the Aladdin license to Virgin. He called Designer Bill Anderson to his office. Anderson was the first in-house designer hired at Virgin, and he had been a part of its “Global Team,” the group that had produced the hit Mick & Mack: The Global Gladiators for Genesis. Thanks to its success on Global Gladiators and later on Cool Spot, the team had first call on any new triple A projects coming into the studio. Bishop considered Anderson to be the best person to come up with something impressive to show Disney, and he wasted no time in getting the ball rolling. Anderson still recalls how he found out that he would be working on adapting Disney’s latest blockbuster. “One morning, I came to work and was asked to come to David Bishop’s office and asked to sit down. There standing was my boss, and to my right was standing (programmer) David Perry, and Mr. Bishop looked me in the eye and said, ‘What are you working on?’ I told him that I was working on the level gameplay designs for Jungle Book. He quickly replied, ‘No you’re not!’ (long pause) ‘You’re working on Aladdin!'”

Bishop and Perry already had a game design document. A team composed of David Bishop, Seth Mendelsohn, Mark Yamada, and Mike Dietz created the design document to present to Disney. The group locked itself inside an apartment for days to complete it over several marathon sessions. Now, they needed something tangible to go with it. Anderson was told that he had 24 hours to come up with a complete level draft. With no time to waste, he rushed home and began working on a concept pitch. He created a gameplay design for the first level, which he submitted the following morning. Virgin Interactive President Martin Alper then drove to Los Angeles to meet with Disney Feature Animation and show them the design document and Anderson’s work. Alper was a gifted salesman, but convincing Disney that Virgin could do animation was no mean feat. Regardless, his colleagues at Virgin were convinced that no one was better suited for the job. “Martin went in and convinced Disney that we were the people who could take animation from Disney animators and put it into a video game,” Dr. Clarke-Wilson once said. “Selling a corporate image is second nature for Mr. Alper, and he has done a superb job of it.”

Indeed, Alper was perfectly suited for bringing Disney aboard. As a founder of the British company Mastertronic, he had helped establish budget software as a viable category in Europe. He then extended operations to North America in 1986 and sold the company to the Virgin Group, which changed its name to Virgin Mastertronic before selling it to Sega in 1991 (becoming Sega Europe). The Virgin side of the company continued its own path, re-branding itself as Virgin Games before eventually settling on Virgin Interactive Entertainment. As president of Virgin Games, Alper responded only to CEO Robert Deveraux and founder Richard Branson himself, and his high rank and personal involvement helped show Disney that Virgin was very serious about collaboration.

Once again, Alper did not disappoint his colleagues. Gilmore and the other Disney executives were very pleased with what he showed them, and Virgin got the license for Aladdin. A second team continued work on the Jungle Book when development began (the main group transitioned back after Aladdin was finished). The Aladdin team had a very small window for capitalizing on the hit film’s momentum. Disney wanted the game to launch alongside the movie’s home video release, and with so much time lost on BlueSky’s effort, less than six months remained to complete the project.

As if the looming deadline weren’t bad enough, there was another major problem. Sega already had the license to develop an Aladdin game on the Genesis, despite the fact that BlueSky’s project had been canceled. In order for Virgin to be able to develop its own game, something would have to be worked out with Sega. With Disney getting more involved in the development of video games based on its licenses and determined to launch the new philosophy with Aladdin, and with Virgin’s crack team of designers and artists working on a new version of the game, Sega’s role would have to change.

Alper personally handled negotiations with Sega as well. He had a previous relationship with the company in Europe, where Mastertronic had been responsible for Sega’s Master System console and game distribution. By the time Sega acquired Mastertronic in 1991, the company’s principle revenue source was the distribution of Sega hardware and software. The close relationship Alper had with Sega made him the ideal person for finding a workable solution that would benefit Sega and allow Virgin to develop Aladdin.

Alper crafted an agreement that had Sega assume a marketing and distribution role, as well as an equal share with Virgin and Disney. At the time, it was the first such deal among major console publishers. The first meeting took place in early 1993 at the Disney offices in Los Angeles. Steve McBeth, the marketing head for Disney, met Alper, Clarke-Wilson, and Perry. They were joined by Sega of America’s Diane Fornasier, Chief Operating Officer Shinobu Toyoda, and Director of Marketing Services Ellen Beth Van Buskirk Knapp. Shortly after the meeting began, Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg joined them. According to Fornasier, he was not in a very chatty mood and was very curt in his comments.

Of course, Katzenberg was not there to be gracious. His task was to make it clear to those involved that a lot was riding on Aladdin’s success, as Disney was planning to enter video game development on its own. Aladdin would be a test run for the company, and Disney was to have final say about what went into the game. If the deal was to go through, Disney would require several assurances. First, Sega would have to devote as many marketing dollars to Aladdin as it would to any top tier game of its own. Essentially, it was to get the same treatment as a game in the Sonic series. Second, he didn’t want it to compete with any Sonic game that might be coming out for the holidays, so Sega would have to release Aladdin earlier. Third, he expected Sega to order a million copies of the game for U.S. distribution, a number reserved for titles that were expected to be top-sellers. Lastly, Katzenberg was to have final word on all marketing materials.

With his demands laid out, Katzenberg left the meeting (he would participate in several more). Virgin and its crack team would give Disney the game engine and animation it wanted, and Sega would promote and distribute the release nationwide. Beyond this role, Sega had no hand in Aladdin’s development other than quality assurance, and a massive effort was made to ensure that the game would be as bug free as possible by launch. Former Sega of America Tester Jennifer Brozek explained the busy work schedule to Sega-16. “I remember a lot of overtime. My normal hours were three p.m. to 12 a.m. (second shift). When we worked overtime, we were usually in the office from three p.m. to four a.m.”

Reportedly, Sega’s only major benefit from the deal was the brand recognition obtained by associating itself with such a high profile Disney product. “Sega told us they didn’t make any money on the deal,” Clarke-Wilson commented via email, “and I believe them. However, it was a huge brand promotion for them and worth it.” This is quite plausible, given the deal’s structure. All three companies would deduct their costs from the total revenue, and the remaining profits were then divided equally. Sega’s overall revenues were on the rise in 1993, and Aladdin’s job was to continue to move hardware and increase brand recognition into the all-important fourth quarter and holiday season. It would also provide some breathing room should the first Sonic The Hedgehog title without Yuji Naka’s involvement, Sonic Spinball, fail to meet sales expectations that fall.

Arabian Knights

With a historic three-way deal between Disney, Virgin, and Sega finally worked out, the race was on to get an Aladdin game on store shelves in time for the VHS release. Virgin Games had been perfecting its Genesis development tools since 1991, and the engine David Perry created for Global Gladiators and Cool Spot had been tweaked for use with Jungle Book. Now, both resources would be pressed into service for Aladdin.

The deal between Disney and Virgin called for Walt Disney Feature Animation to produce hand-drawn character art similar in quality to what was used in the film. This artwork would then be passed on to Virgin for digitization and programming. Three teams worked simultaneously: Disney animators at the Disney Animation Studios in Orlando, Florida, Virgin’s team in California, and a group called Metrolight Studios in Los Angeles, which handled the digital inking and painting process. Digitally painting art was not uncommon in animation at the time, as Disney had used the procedure for production art, like character animation, props and effects. This was done using Disney’s Oscar-winning Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), which debuted with The Little Mermaid and was amply used until 2006. CAPS replaced the clear, plastic cells that had traditionally been placed in registration over backgrounds and photographed in sequence. CAPS was not made available to Virgin, since it was a proprietary Disney system.

Contrary to what one might think, the physical distance between teams wasn’t the biggest problem facing development. Disney wanted to take a more active role in bringing its properties to video games, but it was reluctant to share the film assets needed to match the level of animation quality found in its films. Virgin Games Animation Director Mike Dietz remembered the difficulties encountered at the start of the project. “Disney was very reluctant to share feature film artwork outside of their studio,” he explained to Sega-16 via email.” So as a third party developer, we actually received very little artwork from the film’s production. In fact (as odd as this might seem), we didn’t even have a copy of the film available to us during production of the game.”

Disney was understandably selfish with its prized art assets. After all, hand-drawn animation was the more than just the company’s livelihood; it was its legacy. This, however, didn’t mean that it was unwilling to help Virgin’s efforts. A crew of producers, animators, and artists from Disney Feature Animation was assigned to Aladdin. Additionally, Disney provided Dietz and his team with a full set of color copies of all the film’s backgrounds, providing an invaluable resource for level designers and background artists (and a benefit the BlueSky team never had). These background copies proved extremely helpful. Since they were done in chronological order, they allowed the designers to identify the places of specific scenes in the film. Extensive character model sheets were also provided to Dietz, and he was allowed to view the film (but not permitted to make copies).

Many of the animators and artists assigned by Disney had also worked on the company’s major films, so they were an excellent fit for the Aladdin game. Dietz spent a great deal of time on-site in Florida during the animation production, working with Disney Feature Animation producers Paul Curasi and Chuck Williams, as well as director Barry Cook. This began a relationship for many that continued well after Aladdin, and some of the team would go on to collaborate on other video game interpretations of Disney’s movies. For instance, Artistic Coordinator Ruben Procopio was charged with overseeing the drawn character art, which included both rough and finished animations. He had been at Disney since he was 18 and had worked on such classics as The Little Mermaid and Who Framed Roger Rabbit, but this was his first experience working with video games. He enjoyed the experience greatly and would later participate in Virgin’s The Lion King. Procopio was part of the team that operated out of the Disney studios in Florida, and Aladdin had been assigned to his team while they were between projects.

Dietz’s role was to ease the animators into the confined process of game development, about which they knew little. Working on major Disney films, they were accustomed to having as many frames of animation available to them as needed for any scene, governed solely by acting requirements and assigned screen time. Now, they would have to deal with the limitations of cartridge space, hardware memory issues, and all the other problems inherent with video game design.

Dietz explained the difference between the freedom of working on the film and the very tight quarters cartridges represented. “For games, we had a very limited number of frames we could fit into the cartridges, so we had to come up with all sorts of techniques of holds, loops, X-flipping, palette cycling, etc. There were also other limitations typical of console game production of the time that was foreign to feature film animators, such as limitations on the horizontal width of consecutive sprites on screen or limits on the number of characters we could have on screen at any given time.” Overcoming the differences in formats was not as difficult for Dietz as assuming the director’s role. This would have been an intimidating task for any animator, given the history of his colleagues. “Here I was,” he quipped, “a video game animator with three shipped games to my credit, walking into Disney and telling a crew of feature film animators how I wanted things done. It was like a high school baseball player walking into Yankee Stadium and trying to show them how to swing a bat.”

Dietz explained the difference between the freedom of working on the film and the very tight quarters cartridges represented. “For games, we had a very limited number of frames we could fit into the cartridges, so we had to come up with all sorts of techniques of holds, loops, X-flipping, palette cycling, etc. There were also other limitations typical of console game production of the time that was foreign to feature film animators, such as limitations on the horizontal width of consecutive sprites on screen or limits on the number of characters we could have on screen at any given time.” Overcoming the differences in formats was not as difficult for Dietz as assuming the director’s role. This would have been an intimidating task for any animator, given the history of his colleagues. “Here I was,” he quipped, “a video game animator with three shipped games to my credit, walking into Disney and telling a crew of feature film animators how I wanted things done. It was like a high school baseball player walking into Yankee Stadium and trying to show them how to swing a bat.”

Fortunately for Dietz, his fears were unfounded. The Disney Feature Animation team was very welcoming, and many of them were fans of video games and were eager to learn about game production. Together, they worked out a simple but efficient system for creating Aladdin’s animations. While in Florida, Dietz would create rough sketches and notes of each action sequence, giving the animators a clear vision of what was needed for each scene and the limitations attached. The Disney crew would then create film-quality animation by hand that was still within the limitations of the game engine. This attention to detail was something that was almost a routine at Disney, and the fact that much of the same discipline used for the Aladdin movie found its way into the game greatly contributed to its high quality.

The character art used for the video game had to reflect not only the same artistic style as that of the movie but also the same personality. Players had to believe that the Aladdin running around on their screen was identical to the one they saw in theaters. This was the Disney animators’ most crucial role, and it was one they were more than capable of assuming. To get a clear concept of how familiar their part in the game’s art design was, one need only look at the work done on the actual film. Sega-16 spoke to Dave Pruiksma, who was the supervising animator on the Sultan character in the movie Aladdin. He explained how each character was created. “During this process,” he told Sega-16, “it is important to know who the character is, what his or her role is in the film (personality type, voice, if cast, etc.). The real insight into developing the character comes in the supervising animator’s approach to the character and its personality. In the case of the Sultan, his personality came from my personal feelings about him, as an actor would approach a character. I used an amalgam of sources for the Sultan including a little bit if me, a little bit of my own father, the actor Frank Morgan (from the Wizard of Oz), and actress Marion Lorne who played Aunt Clara on the Bewitched series on ’60s television.”

Once decided, the essence and personality of the characters is then captured in the animators’ art, and the next task was to map out each scene sequence. Animators are issued an exposure sheet, a tool that is common in animated films but that had never before been used in video games. Procopio explained the purpose of the sheets to Sega-16. “The exposure sheet keeps track of all the drawings and how many frames it should be shot at once it gets to the camera department. It also breaks down every frame of the scene. Additionally, not only does it have the pertinent info, like sequence and scene numbers, the footage length, who animated it and scene description, it shows any dialogue broken down into syllables.” From there, imagination is the main tool for creating character-based animation.

The importance of exposure sheets in these scenes cannot be understated. They are vital for ensuring that everyone knows exactly what is expected from them, and they help animators and artists stay on the path that project leaders have developed for the project. Pruiksma detailed the order of things and the importance of everyone being on the same page. “Communication between directors and supervising animators is essential. The directors of the film have the overall story and sequences in front of them at all times. They have the road map for our production ‘trip,’ and they communicate that to the supervisors who communicate that to their animators. All scenes are shown to the directors, but only after they have been gone over with the supervisor and given the thumbs up. The directors make the final approval.”

This attention to detail and professional discipline brought Aladdin’s characters to life, and that liveliness that was central to the video game adaptation’s success. Without it, the special charm so inherent to Disney would be missing, and Virgin would be facing the same dilemma that resulted in the BlueSky version being canceled. But trying to capture Disney magic in a cartridge is not easy. All that quality animation was worthless unless it could somehow be put into a game cartridge. Luckily for Disney, Virgin knew how to do exactly that.

All Eyes on Agrabah

While many other game companies had tools that could optimize character sprite counts for better animation, none were as sophisticated or had received as much attention and research as Virgin’s. As a result, its custom process was able to produce cartoon-quality animation in a manner the competition could not emulate. Virgin marketing labeled this process “Digicel,” but what many believed to be an actual machine or software tool set was actually a combination of factors. “Digicel isn’t a single thing,” Clarke-Wilson confessed. “It’s a marketing name we made up after the fact. It’s a whole pile of tools and processes and talented people.” It was certainly perfected after Aladdin’s success, as evidenced by the fact that the inking work Metrolight Studios had been contracted for was now being done in-house by Westwood Studios for Virgin and Disney’s next collaboration, The Lion King.

The Digicel process was essentially composed of two major steps. First, the hand-drawn artwork was digitized in a manner that would not compromise its integrity. Second, the animation had to be compressed in order to allow for the necessary amount of frames. Though perfected for Aladdin, this process was not a product of that deal. Previously, another team at Virgin, including programmer John Alvarado and producer Andrew Luckey, had initiated a process for digitizing hand-drawn animation for video game consoles. This was to be incorporated into another game but was quickly adapted for Aladdin. Dietz detailed to Sega-16 how the process was adapted and developed. “Our technology was an extension of theirs and stood on the shoulders of their hard work. In fact, I believe when Disney saw the work that John and Andy’s team had done digitizing hand-drawn animation, it ended up being a big part of why Disney chose Virgin for the Aladdin project.”

In reality, what made the Digicel process so unique was the well-honed skills of the people involved and how well they were able to combine those skills towards a common goal. The art done by Disney animators was first scanned and digitally colored by Metrolight, then compressed for frame optimization. This compression resulted in a loss of detail, and Dietz’s team had to touch up the characters to bring them back to the quality level of the original artwork. This was a vital step to the procedure, as a failure to maintain the integrity of the original artwork would produce results that could easily be mistaken for ordinary pixel art.

Once the art was transferred to the game engine intact, the next task was to animate it. The sprites were programmed into the game using exposure sheets, something that Programmer David Perry was likely the first in the game industry to embrace. Their use gave Aladdin’s animators extensive control over how each sprite would look in-game and guided Perry, who created complex animation scripts to reuse of older frames. He outlined the benefits of the process to Sega-16. “The result was timing based on individual frames and clever repetition, this required a technical understanding of how to process the animation and that’s where the Animation Director Mike Dietz really brought it home. That tech was backed up by Andy’s tools finding the optimal way to compress and re-use blocks to squeeze every last frame in there.”

A Whole New World of Design

With the character animation well under way, the rest of the design team battled to complete the rest of the game. It was a feverish pace, with long hours and constant communication between members. Perry recalls just how exhausting the entire ordeal was. “Aladdin was a crazy project. I was so tired, sometimes I’d just walk out to the parking lot and fall asleep in my car.”

A key factor that made the short development window viable was the use of Perry’s Cool Spot engine, which underwent a great deal of revision when utilized for Global Gladiators and Jungle Book. The latter game was put on the back burner when the Aladdin deal was reached, but Perry had been able to make significant improvements to its version of the engine, including some upgraded image handling tools created by fellow programmer Andy Astor. These tools were instrumental in compressing and re-using blocks to maximize the use of every frame for animation, and their development was quite timely for the urgent task Virgin Games was now undertaking.

One of the unique properties to Aladdin was the inclusion of a crisscrossing platform system. This innovation made significant modifications to the way game characters progressed through levels. Traditional platform titles were straightforward in the design of the character’s path. Typically, players would traverse a landscape to get from one point to the other, but Aladdin’s design called for a less linear approach. To meet this need, Perry had to overhaul the engine’s contour system. Changes also had to be made to how the game’s levels were set up in the editor so that they would function properly. Despite the extra work, the changes resulted in greatly expanding the character’s path options. “In Aladdin there were two paths that the player could move on,” Anderson said, “and by special placement of hidden tags I could control which path the player character could take. This allowed for zigzagging paths that we couldn’t do before.”

Perry was constantly adjusting the engine in order to accommodate the latest demands from Anderson and his team of level designers. “Designers like Bill always want more,” he said, “so suddenly we needed hidden spaces, trap doors, floors with switch backs, 3D depth on a 2D floor, etc. The needs were endless, so we had to continuously upgrade the ways we track the floors. In the end, the floors and the worlds had no assumed relation, so if Bill wanted he could have you run off into the sky.”

Perry and his colleagues managed to work quite well in the fast-paced environment inherent in such a short development cycle. He made it a priority to get the latest revisions of each team’s work into the game as quickly as possible, and the ability to see the latest builds at a constant rate helped build momentum. Though the pace was taxing, Perry has fond memories of working to get everything together. “I remember watching them sometimes rush back to their desks to make some adjustments, the fact that they were really ‘on it’ forced me move quickly.” Disney was also in the loop, being kept up to date at regular intervals of the progress being made. Though the actual game design was Virgin’s responsibility, Disney had the final word on what could and could not be included. Clarke-Wilson mentioned how connected they were. “Disney had final approval, and they received cartridges on a regular basis (actually I think they had a development machine and we modem’d up the latest version for them to see and play).”

Indeed, Disney was quite involved throughout the design process. Jeffrey Katzenberg was very hands-on in the game’s development, and he contributed several ideas, including many of the site gags that are present throughout each stage. For instance, it was his idea to have the Sultan’s guard’s show polka-dotted boxer shorts when their pants dropped while fencing with Aladdin.

With all the motion going on at Virgin and so many game elements being designed simultaneously, a few things were bound to be left on the cutting room floor. Amazingly, Aladdin had very little cut or changed for the final product, with only two real alterations being made. The first was the between-level cut scenes that would further the plot. These would feature scenes from the film that would transition into the next level to be played, beginning with the first level. It was felt that there was no need for them, given the popularity of the film and the faithfulness of the level design.

The second change was to the bonus stages. Originally, there were to be three mini games that could be accessed by obtaining a special token from a specific enemy rather than just finding a Genie or Abu token. The main bonus stage, featuring Abu, was initially going to have him fighting off only guards without having to avoid any dropping pots. If he were hit, Aladdin would dash in and rescue him, leaping off-screen before the guards could react. In the slot machine bonus stage, the machine was to have an arm, giving it the appearance of the classic one-armed bandit. However, focus group reactions were negative to the casino-like feature, so the arm was removed. Finally, a third game had Aladdin playing a game of rock, scissors, paper with the magic carpet (similar to Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle). This stage was omitted entirely from the final version of the game.

Most interestingly, there was supposed to be a Sega CD version of Aladdin, due sometime after the cartridge original hit store shelves. It was canceled early on though, as Virgin’s priorities shifted to completing Jungle Book. The departure of Perry and several other key team members during that game’s development most likely closed the door on any chance of a release. A lamentable turn of events to be sure, as this enhanced edition would have featured new throwable items (snowballs), new animations, and all-new exclusive levels, including several where Aladdin wears his Prince Ali outfit. The Genie was also to appear after his lamp was recovered in the Cave of Wonders. He would show up during Aladdin’s idle animations to encourage him with clips of real speech. Moreover, some of the original stages would have new obstacles, like cacti and quicksand in the desert. Several were to also include new boss battles. The desert , for instance, would pit Aladdin against a giant sand snake, and the Sultan’s dungeon would have him battle Razoul in order to reach the exit. Additionally, Jafar would assume a third form after his snake transformation at the end of the final level. Players would have had to contend with his evil genie form in order to complete the game.

Sounds of the Desert

One of the most important ingredients for creating a truly worthy adaptation of a Disney film is undoubtedly the soundtrack, and Aladdin’s Oscar-winning score was a major factor in the film’s popularity. Composer and Virgin Games veteran Tommy Tallarico had a major interest in using the Genesis’ sample channel, and he knew how rich a game’s music could sound when the channel was employed correctly. Yuzo Koshiro, for instance, had made excellent use of it for Streets of Rage, giving that game real samples of Roland keyboards that enhanced the soundtrack to incredibly dynamic levels. Tallarico knew he could use the channel to make Aladdin’s music as close to the film’s as the hardware would allow. “Back in the old days on the Sega Genesis,” he told Michael Thomasson of Good Deal Games in 2003, “people would use the sample chip to play a scratchy voice sample (‘FIGHT’) or use it to intro the company name (‘SE-GA’) I decided why not have that sample channel be playing as much as possible? I had convinced programmers that if they gave me enough space I would make the Genesis sound like no one has ever heard.”

The sample channel would be needed if Tallarico was to do the score justice. In order to create a believable recreation of Agrabah and Aladdin’s adventures therein, it was vital that Alan Menken’s classic themes make the transition to the Genesis intact. To accomplish this, Tallarico had to work with each song note by note, in order to determine how to best make use of the Genesis sound chip. He brought aboard Composer and Orchestrator Donald Griffin, who arranged five songs from the film and created another five original pieces, including Turban Jazz and Arab Rock 1 & 2. Tallarico selected songs from the movie and sent a copy of each one to Griffin, who would then reduce it to a smaller, voiced MIDI file. Once completed and returned to Tallarico, he had to determine how to best fit the audio capabilities of the Genesis to each note. “I would literally go through every single note in every single MIDI file of the entire game one by one to assign it the proper sound, value, priorities, length, volume, etc.,” he told Sega-16 in 2005, “it was a painstaking process but one that I think was well worth it.” He found the melodies from the film easy to break down, and the difficult part was balancing each song with all the sound effects so that as little of the music as possible would be dropped when the effects played. This difficulty was overcome by prioritizing every sound that was used, so that the sample chip was constantly playing, leading to very little drop out.

Tallarico handled the conversion to the Genesis audio, as well as incidental transition music. Though the work could be tedious, he found ways to lighten the mood in the studio. For example, each song Griffin gave him was numbered, and Tallarico assigned names to each of them to make sorting easier. Griffin remembered the fun Tallarico had with the songs he sent him. “The one he called Rug Ride he eventually re-voiced to all piano (sounding like two frantic Liberaces) and put it on Virgin’s telephone system for several months. I never knew until I was put on hold the first time!”

From Street Rat to Sega Sultan

Inside a booth packed with press, Aladdin was finally unveiled on Friday, June 4, 1993 at the summer Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Chicago, a show most noted for the final public appearance of Sega’s virtual reality headset and the debut of the Panasonic 3DO. Katzenberg made it a priority to present the game personally, and he scheduled the event right after the industry breakfast early in the morning, so that it would be among the first items viewed. Demo kiosks had been set up the night before, and each was covered with a black cloth to give no indication of the spectacle to come. The actual EPROMS themselves were locked in the hotel safe, to be brought out only under Katzenberg’s explicit instructions. In all, Sega had as many demo kiosks for Aladdin as it did for Sonic Spinball, and both games were pushed equally at the show.

Representatives from all three companies were present to launch the game, and they were eager to see the results of this unique collaboration. Katzenberg was willing to spare no expense to present Aladdin to the world with the largest bang money could buy, so he had the press event held in a ballroom near Sega’s booth. In typical Disney fashion, he had something ready that was sure to capture the attention of everyone present, and massive screens and costumed dancers awed the press. Perry recalled the event to Sega-16. “Richard Branson and Jeffrey Katzenberg did the announcement, and the doors opened, and all the costumed Aladdin dancers came in. He and Branson launched it together to about 1,000 press members with a full stage show. It was absolutely shocking for a video game launch.” Ellen Beth Van Buskirk Knapp also remembered the grandeur of the announcement. “Disney took a hotel ballroom and transported into an Agrabah marketplace, replete with livestock, actors and actresses, live music, props, sets, palm trees, and magic.” Gilmore remembers a crowd forming instantly around the demo kiosks, and that press members were convinced that the game had some special effects chip inside the cartridge.

Representatives from all three companies were present to launch the game, and they were eager to see the results of this unique collaboration. Katzenberg was willing to spare no expense to present Aladdin to the world with the largest bang money could buy, so he had the press event held in a ballroom near Sega’s booth. In typical Disney fashion, he had something ready that was sure to capture the attention of everyone present, and massive screens and costumed dancers awed the press. Perry recalled the event to Sega-16. “Richard Branson and Jeffrey Katzenberg did the announcement, and the doors opened, and all the costumed Aladdin dancers came in. He and Branson launched it together to about 1,000 press members with a full stage show. It was absolutely shocking for a video game launch.” Ellen Beth Van Buskirk Knapp also remembered the grandeur of the announcement. “Disney took a hotel ballroom and transported into an Agrabah marketplace, replete with livestock, actors and actresses, live music, props, sets, palm trees, and magic.” Gilmore remembers a crowd forming instantly around the demo kiosks, and that press members were convinced that the game had some special effects chip inside the cartridge.

Katzenberg detailed Aladdin’s revolutionary development, citing the ground-breaking animation and art that had been brought to bear. He made sure to emphasize Disney’s role in the the process and how the game would serve as the launch pad for his company’s new foray into interactive entertainment. He was followed by Branson, who played up the crowd with stories of how he obtained his success. He then showed a video of a failed skydiving attempt and how he hired the man who rescued him, ending his turn with a history of how Virgin Games came to be. Last was Kalinske, who had to close the presentation with details about Sega’s marketing and distribution plans for the game. He illustrated Sega’s commitment to making Aladdin a hit title and showed the upcoming television spots, a sign of how much effort his company would put into pushing the game. According to those present, Kalinske gave an excellent presentation, but even with his panache for promotion, it must have been a hard task to follow the spectacle of dancers and life-and-death video presentations with just business talk.

Hollywood flair, extreme enthusiasm, and industry know-how combined to impress the media in a major way. Press hype around Aladdin started to swirl almost instantly, with magazine after magazine running previews and providing the latest information on the game’s progress. One could speculate that the exciting CES reveal and the resulting press coverage alone were enough to make Aladdin a hit, but it soon became evident that it was as much substance as style, and the positive buzz surrounding it soon snowballed into great sales.

Sega was quick to take advantage of the situation and went into full marketing mode. With the aid of the Manning, Selvage and Lee public relations company, $4 million was slated to promote the game, which included everything from television commercials to pamphlets included in the upcoming VHS release and media tour in New York and Los Angeles. Disney had mandated that the difficulty level for the final version be ramped up significantly after the first few levels, since it was targeting an older demographic with the game. This strategy also allowed Sega to produce a television ad that, while in line with its own “Sega Scream” campaign, was edgier than most Disney advertising. The 30-second spot featured a boy telling his two friends how he found the Genie’s lamp and wished for a copy of the game. He then uses his two remaining wishes to turn one friend into a dog and the other, more obnoxious one into a fire hydrant.

Disney’s move to include an older audience did not originate with the Aladdin game. The movie itself was a major departure from the traditional brand of animation for which the company was known, and itself had been considered a gamble. Instead of simply creating family-friendly movies, Disney was now looking to broaden its base and entice older movie goers by adding contemporary references and jokes that younger children wouldn’t understand. With this realignment, it was hoped that adults could view Disney’s films as more than just cartoons they took their children to see, and instead as products that had something for them as well. The philosophy began with The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, and with Aladdin, Disney had gone all-out to add a cross-generational appeal to its products. This new line of thinking was applied equally to its game software.

After almost a half year of work, Aladdin was finally completed to the tune of between $1 and $1.5 million, about four times the average cost at the time. It was released on October 19, 1993, three weeks after the movie hit VHS (and a month before Sonic Spinball). To say it was a success would be an understatement. Only the first two Sonic The Hedgehog titles sold more, and Aladdin went on to ship over four million copies, far beyond the 1.75 million sold of Capcom’s SNES version. Shinji Mekami, who served as the designer on the Capcom game, expressed his preference for the Genesis game in a 2014 interview with the news website Polgyon: “If I didn’t actually make [the SNES game]” he said, “I would probably buy the Genesis one. Animation-wise, I think the Genesis version’s better. The Genesis version had a sword, actually. I wanted to have a sword.”

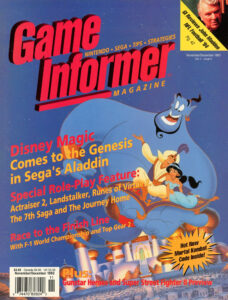

The praise went far and wide when Aladdin hit retail shelves. Video game magazines like Electronic Games and Game Informer praised the game, making it their cover story. It was also honored with multiple industry awards, including “Best Game of 1993” by Electronic Gaming Monthly and the Reader’s Choice award for “Best Music” by GamePro magazine. Press and gamers alike were awed by the incredible animation and gameplay, and the Genesis received another classic title in its library.

A Classic in Every Sense

As successful as Aladdin was for Sega, one has to wonder why there were no further collaborations of this nature with Virgin Games. The simple answer is that Aladdin represented a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, that incredibly rare occasion where all the necessary elements fall into place to make something happen. Disney’s decision to jump into game development came at the same time that Virgin Games was tweaking its process for flawlessly transferring hand-drawn animation to gaming and Sega was willing to distribute another company’s high profile title without being the major creative voice. The stars aligned for Aladdin and Aladdin only, and later Disney games would not see such attention by so many companies. Sega had no interest in Jungle Book due to its poor sales on the Master System, and that game was eventually published by only the newly rechristened Virgin Interactive Entertainment. Jungle Book would suffer a major creative shakeup of its own when key members Perry, Dietz and Doug Tenapel defected to form Shiny Entertainment and create Earthworm Jim. With Virgin’s star team disbanded, the game was handed over to Eurocom Entertainment Software for completion. The next great Disney feature, The Lion King, was also done by Virgin, and it did well but did not attain the same level of success as Aladdin. Sega was not offered a role, and it would probably have declined regardless, as all of its focus was on its Sonic brand and the release of Sonic The Hedgehog 3 and Sonic & Knuckles.

Beyond being an incredibly fun game, Aladdin serves as a reminder of what happens when some of the greatest minds in gaming come together with the goal of creating the best piece of software possible. The perfect cocktail of corporate decision-making, creative fluidity, and marketing mastery gave Genesis gamers one of the best titles ever released for the console, and it showed how capable video games were of capturing the spirit and personality of cinema. It brought Disney directly into game development, leading to fan favorites like Mickey Mania and a host of others that continue to this very day. Aladdin was a magic carpet ride of beautiful visuals and polished gameplay that faithfully recreated the original film’s charm and substance, and it stands the test of time both as a video game and as an example of perfect creative collaboration.

“One jump ahead” indeed…

Sega logo & Disney characters courtesy of Disney Wiki. Agrabah street shot courtesy of Disney Screen Caps.

Sources:

- Capcom. (2002, May). Company profile.

- Clarke-Wilson, S. (1997). Fun with Martin Alper. Above-the-Garage.com.

- Daly, S. (1992, Dec.4). Disney’s got a brand-new Baghdad. Entertainment Weekly.

- Griffin, D.S. (2004). Entry on Aladdin Score. Computer-Music Consulting.

- Harmon, A. (1993). Disney rubs the video lamp: Entertainment: The studio finally enters the high-tech interactive market by announcing a partnership to create “Aladdin”–the game. Los Angeles Times.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Feb.). Personal communication with Diane Fornasier.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Feb.). Personal communication with Ellen Beth Buskirk Knapp.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Feb.). Personal communication with Ruben Procopio.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Bill Anderson.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with David Perry.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with David Pruiksma.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Jennifer Brozek.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Joseph Moses.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Mike Dietz.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Tom Moon.

- Horowitz, K. (2014, Jan.). Personal communication with Patrick Gilmore.

- Horowitz, K. (2013, Dec.). Personal communication with Dr. Stephen Clarke-Wilson.

- Horowitz, K. (2006, Nov.). Interview: Ken Balthaser. Sega-16.com.

- Horowitz, K. (2006, March). Interview: Dr. Stephen Clarke-Wilson. Sega-16.com.

- Horowitz, K. (2005, June). Interview: Tommy Tallarico. Sega-16.com.

- McWhertor, M. (2014). Aladdin Designer Shinji Mikami on Why the Genesis Version Is Better. Polygon.

- Thomasson, M. (2003). Interview with Tommy Tallarico. Good Deal Games.

Pingback: Disney’s Aladdin (EU,JP,US) (1993) (Action Platform) (Mega Drive / Sega Genesis) – Johnny Game Over MAG

Pingback: Aladdin (Sega / Virgin) – Hardcore Gaming 101

Pingback: Game Sack – Same Name, Different Game | Videos Kiss

Pingback: Game Sack – Same Name, Different Game | Hackers Hotel

Pingback: Game Sack – Same Name, Different Game | Hackers Hotel

Pingback: Los 10 mejores videojuegos de películas - Kraken Machines Blog

This was an extremely informative article. I knew bits & pieces of the games development but I had no idea that Blue Sky was originally developing a title. Good work on this piece!!!!