A Growing Rivalry

While Sega Sports began to acquire a life of its own, Sega executives saw the potential the brand had for taking a piece of the pie that Electronic Arts had been enjoying almost single-handedly for years. With franchises such as Madden and NHL Hockey, the publisher had a firm grip on several types of sports that few others could match. Sega of America felt that its stable of titles was capable of competing with EA’s, and the massive revenue sports games generated in the U.S. would be vital for amassing the war chest necessary for the eventual transition to newer, 32-bit hardware.

The entire product development and marketing team viewed EA as competition, and they weren’t afraid to take on the goliath. “We were removed from third party marketing, since it was managed by a different group,” Fornasier said, “so we saw EA as a direct competitor, even though they were on our system.” The team took their view of the competition seriously, focusing their marketing on convincing consumers of the superiority of their titles to EA’s and all others. The effort worked, and by the end of 1994, Sega’s share of the sports title market had increased from 20% to 40%. It was even out-selling Electronic Arts in certain sports, such as baseball. The NFL series was enjoying great success against Madden, and the Sega Sport’s group was confident that it had a solid money maker in the brand, one on which SOA could consistently rely.

The entire product development and marketing team viewed EA as competition, and they weren’t afraid to take on the goliath. “We were removed from third party marketing, since it was managed by a different group,” Fornasier said, “so we saw EA as a direct competitor, even though they were on our system.” The team took their view of the competition seriously, focusing their marketing on convincing consumers of the superiority of their titles to EA’s and all others. The effort worked, and by the end of 1994, Sega’s share of the sports title market had increased from 20% to 40%. It was even out-selling Electronic Arts in certain sports, such as baseball. The NFL series was enjoying great success against Madden, and the Sega Sport’s group was confident that it had a solid money maker in the brand, one on which SOA could consistently rely.

Sega management was equally confident in its sports titles, and it considered them essential to sustained success. The genre represented most of the best-selling games developed or produced by the publisher’s American side, and a large compliment of producers worked closely with marketing to ensure that they reflected the latest technology and features. Even the 32X received a share of the portfolio early on, with titles covering a range of sports, including racing, golf and baseball. This attention was short-lived, however, as the difficulty in getting the 32X and Genesis processors to communicate effectively caused most developers to ignore the machine completely. Even Sega itself relegated 32X sports development to ports of Genesis titles that did little to take advantage of its capabilities. There were actually proprietary football, basketball and hockey games in development for the 32X at the same time that teams were working on versions for the fledgling Saturn, but programming difficulties, combined with the poor sales performance of the maligned mushroom add-on and Sega’s struggles to effectively introduce its new, CD-based 32-bit machine, forced the company to cancel those projects early on and focus its dwindling resources on the Saturn releases.

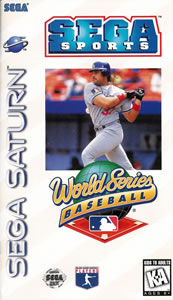

Ironically, the focus on sports titles didn’t extend to the Sega CD. Though there were Sega Sports titles being regularly released on the Genesis, and to a lesser extent the Game Gear, the CD add-on reportedly didn’t provide enough processing power for sports games to be much more than cartridge ports with full-motion video introductions and cut scenes. Sega initially dabbled in bringing its sports line to the CD, releasing a version of Joe Montana Football. However, the development of that title proved to be a nightmare for ACME Interactive (the same company behind the excellent Evander Holyfield’s “Real Deal” Boxing on the Genesis, though different teams worked on both games), reportedly because of problems with the main programmer, and this caused efforts on the CD version of World Series Baseball to be halted early on during the development cycle. Unlike Joe Montana’s NFL Football, the project made no effort to utilize the power of the Sega CD. Scott Rohde succinctly detailed to Sega-16 why the game never made it past the alpha stage. “World Series Baseball on the Sega CD was essentially the Genesis game with cool video fly-ins to every stadium. That’s all it was.” Interestingly enough, the 32X version managed to bunt its way onto store shelves, perhaps owing its release to the fact that it was instead developed by BlueSky Software, the same group behind the excellent Genesis versions.

The only other Sega Sports title to ship on the Sega CD was Prize Fighter, most likely because it was developed by then-popular Digital Pictures and featured gameplay entirely based on full-motion video (FMV). Considered widely to not be a “true” sports game, Prize Fighter may have actually had a better chance at seeing release than World Series Baseball for the very reason many gamers avoid it. Games comprised of full-motion video were in great demand at SOA at the time, as they were considered to be excellent examples of the capabilities of the Sega CD. Additionally, the multi-media revolution was in full swing and touted by many developers as the wave of the future and the natural evolution of gaming. Unfortunately, most FMV titles fall short on gameplay due to long loading times and limited interaction. Prize Fighter fared only slightly better than other games in the genre in this regard, but these factors are most likely why many gamers tend to place it in the FMV category rather than count it as a true sports title.

With no flagship sports to lead the software charge on the 32X and Sega CD, along with tepid sales on the Game Gear, Sega shifted gears once again and put all its strength into its popular Genesis line. New installments to multiple franchises were arriving yearly, such as football and baseball (both endorsed in 1995 on the Genesis and 32X by Deion Sanders, a unique opportunity to sign a two-sport celebrity), and Sega slowly – perhaps too slowly – prepared to leave the Genesis behind and bring its sports line up to a more powerful machine. Unfortunately, the transition would not be a smooth one for the company as a whole and especially for Sega Sports. Sega’s procrastination with its sports brands caused other developers, such as 989 Studios, to swoop in with a powerful line of titles that took it completely unaware. Games like NFL Gameday, NHL Faceoff and In the Zone left Sega scrambling to catch up. Soon, its rivalry with EA would fizzle out as its development and marketing budgets were targeted elsewhere, allowing the Madden publisher to concentrate on new pretenders to its throne. There would be lasting repercussions for Sega from this fracture with EA that would ultimately contribute to its departure from the hardware market entirely.

A Decaying Orbit around Saturn

The consistent success the Sega Sports brand had enjoyed since 1993 would slowly wind down after the Saturn arrived in May of 1995. That year found Sega in flux, trying to phase out its multiple 16-bit hardware pieces while it fought an uphill battle to convince consumers to embrace the new Saturn over Sony’s dynamic Playstation console. Wayne Townsend explained to Sega-16 via email how the console’s surprise U.S. launch in May of 1995 and competing Sega hardware caused confusion among consumers and delays with developers. “The Saturn may have had comparable performance,” he said, “but our developers struggled getting the most out of the machine in a timely fashion, which hastened its demise in my opinion, along with its price point, the market confusion caused by the 32X introduction the previous year, and the Sega CD.”

Sega may have beaten Sony to retail, but the early start did little to stimulate buyer confidence. There was only one Sega Sports title, Daytona USA (led by John Gillin, Director of Sega Sports Marketing), available at launch, and while gamers lauded its smooth controls and excellent track design, its lackluster visuals made it look less appealing to many than Namco’s Ridge Racer on the Playstation. Worse, it would be the only sports title available on the Saturn in America until Worldwide Soccer arrived in August of that year.

The delay may well have been a sign of things to come for Sega Sports, and eventually there would be massive internal restructuring occurring within Sega of America. The branch’s original product development (PD) group evolved into a separate studio called SegaSoft, which focused largely on the Heat.net online playing service on PCs. The Sega Technical Institute, renamed SOA PD, was reorganized to fill the void and played a much larger role in product development, shifting beyond its traditional capacity as a maker of character-based platform games and Sonic titles. It was now responsible for sports titles, movie licenses and the localization of Japanese games.

With the dismantling of the proper Sega Sports group, development of titles now fell to SOA PD and a small core of external producers who had to scrape together whatever new software they could.Former STI alumni and SOA PD producer Mike Wallis shared with Sega-16 the pride the group felt regarding its new position within the company. “The atmosphere at the new SOA PD group was one of excitement because we were charged with carrying the mantel for Sega first party products.” This was a major change from the isolated, small developer atmosphere Wallis and the other STI members were used to, and they were quickly tasked with bringing the next installments in several Sega Sports titles to the Saturn. The new group set out to take the tradition begun on the Genesis and bring it into the next generation in large fashion.

One license that was affected was NBA Action, which was handed off to Canadian developer Gray Matter Entertainment Software. Spawned from Sega’s first American-made basketball title, which was bore the name of San Antonio Spurs legend David Robinson and initiated a series that ran for several years on the Genesis, NBA Action seemed to fit the new attitude at Sega about Saturn releases going in different directions than their 16-bit predecessors. Gone was the celebrity from the title, and the game was now entirely rendered in 3D.

Unfortunately, its sales were underwhelming. Poor market performance and the demise of Gray Matter forced Sega to put the franchise on hold in 1997, forcing Saturn-owning basketball fans to turn to EA for their fix. It was only when a new developer approached Sega that the series’ return received the green light by management. Wallis and his group worked closely with them to create a game that would better represent the Saturn’s capabilities and offer NBA fans the game they had been anxiously awaiting.

NBA Action ’98 was the only the second game in the series on the Saturn in three years, and by this time Wallis and his colleagues were working hard to stem the migration of basketball fans to Sony’s In the Zone and EA’s NBA Live. Both of those games were extremely polished and popular, and it was becoming increasingly harder to convince consumers to stick with the Saturn and its diminishing market share. By the time NBA ’98 arrived, the only hint of Sega’s licensing past that remained was a young Kobe Bryant on the cover. Aside from this nod, no other mention of a superstar endorsement is made. Sega’s sports games had now come full circle, returning to the original marketing trend used during the Master System and Genesis days, and one Sega Sports would continue to use for the rest of its run. The change echoed moves by other companies like EA, where famous athletes graced the covers of each year’s sports installment but had no actual involvement in their development. Without the level of presentation the more developer-friendly Playstation allowed, Sega’s game had to instead concentrate on gameplay. This was something NBA Action could do well, as it was now programmed to take advantage of the strengths of the Saturn and not overtax it. Emphasis was thus placed on the new features that the more powerful hardware could provide.

Wallis detailed the new direction. “Around that time, a company called Visual Concepts in Novato, CA approached (research & development head) Manny Granillo to showcase their 3D sports tech. These guys were passionate about being sports nuts, and they had 3D technology, but equally important, they had a strong AI approach to player actions. This intelligent approach would allow us to attach, via motion capture, intelligent player behavior to the game, which was something that nobody had really done up to that point. What I mean by this is that if you had a power forward or center in the paint, they could back down the defending player in order to get a high percentage shot.”

Granillo and Wallis structured a deal to have Visual Concepts deliver the next NBA Action, and the group quickly began to implement their new technology to move the series forward. Among the areas receiving major improvements thanks to the focus on AI were significant increases in intelligence, players actions being more determined by their season statistics than before, and increased adjustments to offensive and defensive statistics, such as blocked shots being as important as field goal percentage. Many of these features proved to be so innovative that they even found their way to EA’s NBA Live series the following year.

Though NBA Action ’98 failed to eclipse the competition, it was still considered successful by Sega and marked the beginning of a historic relationship with Visual Concepts, the developer that would eventually be acquired by Sega and go on to achieve massive acclaim and sales. It was awarded the contract for the 1999 follow up, but Sega’s emphasis was quickly switching to the upcoming Dreamcast. Instead, Virtual Concepts left the Saturn behind and began to develop for the newer console, an effort that would have massive consequences. Unbeknownst to gamers at the time, Sega’s sports line was playing a major role in shaping its future and that of the sports genre in general, even as Sega itself was losing the console war.

Contrary to the success Sega was having with its basketball series, its football game was taking a beating. the NFL franchise was stopped cold after only a single outing – which didn’t arrive until a full year after the Saturn debuted – by 989 Studios’ NFL Gameday, a game so complete that it even took EA by surprise, causing the company to shelve the 1996 edition of Madden as it scrambled to find out how it had been outclassed in its signature sport. The debacle that was the ’96 version of Madden allowed Gameday to arrive on the Playstation first, setting the stage for a decade-long war between the two series. Ironically, the team that had been behind EA’s canceled 32-bit football debut was none other than Visual Concepts; the very creators who would soon move on to develop Madden’s future nemesis, NFL 2K.

With the rise of yet another competent rival, Sega’s own football series was all but forgotten. It received only two releases during the Saturn’s entire three-year lifespan (’96 and ’98). Similar to what happened with the Sega CD and 32X, the lack of solid and consistent representation in key areas of Sega’s former sports line on the Saturn helped drive fans away from its hardware, this time into Sony’s embrace, and the battle for sports dominance during the entire 32-bit generation was fought between two publishers – EA and Sony – leaving Sega on the sidelines.

There were still a few bright spots for Sega Sports. The World Series Baseball franchise was in top form, and it is considered by many to be the best baseball series of the era. Additionally, the Model 2 and Sega Titan Video (ST-V) arcade boards were producing many of the Sega Sports titles released during the Saturn’s lifespan, such as Sega Touring Car Championship, Winter Heat and Manx TT Superbike (which, along with Hang-On GP, did not bear the Sega Sports logo on its cover in the U.S., though both did have it in-game). Racing was one of the strongest areas for the brand, with Sega Rally and Daytona USA Championship Circuit Edition offering solid gameplay and impressive presentation. Sega also used its arcade roots to branch out the Sega Sports line into other areas not covered before, releasing solid games in a wide variety of sports. For example, Decathlete gave Saturn owners an excellent track and field game, and was successful enough for a sequel called Winter Heat. Additionally, 1997’s Steep Slope Sliders let gamers effortlessly snowboard through several courses through an innovative button-based combo system.

There were still a few bright spots for Sega Sports. The World Series Baseball franchise was in top form, and it is considered by many to be the best baseball series of the era. Additionally, the Model 2 and Sega Titan Video (ST-V) arcade boards were producing many of the Sega Sports titles released during the Saturn’s lifespan, such as Sega Touring Car Championship, Winter Heat and Manx TT Superbike (which, along with Hang-On GP, did not bear the Sega Sports logo on its cover in the U.S., though both did have it in-game). Racing was one of the strongest areas for the brand, with Sega Rally and Daytona USA Championship Circuit Edition offering solid gameplay and impressive presentation. Sega also used its arcade roots to branch out the Sega Sports line into other areas not covered before, releasing solid games in a wide variety of sports. For example, Decathlete gave Saturn owners an excellent track and field game, and was successful enough for a sequel called Winter Heat. Additionally, 1997’s Steep Slope Sliders let gamers effortlessly snowboard through several courses through an innovative button-based combo system.

However, despite the solid gameplay of these titles, they were little more than arcade ports, and Sega’s internal turmoil affected Sega Sports heavily, leaving it without the large selection of deep, western projects that had originally made it so successful. The inclusion of so many arcade ports is viewed by some as a desperate attempt to capitalize on any brand recognition the sports line still had, with Sega applying the logo generously to games that had not been traditionally considered worthy of the label. “Sega Sports still existed,” Rohde recalls, a twinge of sadness in his voice, “but it was more just like a label; it wasn’t a strictly-managed brand. Sega was just kind of hanging on, and there were people that were just saying ‘hey, we have this Sega Sports logo. Let’s essentially slap it on to anything that smells like a sport.'”

This explains why there were non-traditional sports games on the European Saturn that used the Sega Sports logo. During the Genesis era, there were separate marketing divisions for each territory, such as North America and Europe. The lead development group on a particular game received first rights to things such as features and branding. For instance, North American teams for sports such as American football, baseball and basketball had priority over other territories, and Europe led on sports like soccer and tennis. After SOA dissolved its relationships with most of the American developers responsible for making games under the Sega Sports banner, there were no longer any restrictions within the company as to who had priority to publish under the logo and who could not. Just as SOA was applying it to titles that would normally not have been considered part of the brand, Sega Europe was using it for its own sports games.

Even with all the problems the Saturn experienced, Sega Sports still managed to produce quality titles in the majority of its releases. Again, this is mostly owed to a slew of quality ports from Japan, ironically, the very sort of games which Sega Sports was originally conceived to supplant. However, these releases could not reverse the Saturn’s shrinking fortunes as a hardware contender, and as with the 32X before it, the lack of definitive and consistent first party football and basketball entries proved to be an anchor around the console’s neck that helped sink it in America. There would be nothing more Sega Sports could do to save the dying 32-bit machine, and the brand was forced to lick its wounds and await the transition to the next generation of hardware.

Pingback: Sega-16.com Explores the History of Sega Sports | Put That Back