But what about Hector’s interview with GamesTM, where he specifically recalls meeting with MJ and how the latter worked up a complete soundtrack? It’s possible that while there was indeed some collaboration between Jackson and the STI, none of it had the approval of SOA or SOJ management. Neither Hector nor Drossin ever mention the higher ups at Sega approving anything, and Sonic 3’s own marketing director, Pam Kelly, has no recollection of any negotiations between the two parties. Even the very president of the U.S. branch doesn’t recall negotiations of any kind, and if you’ve read our interview with Tom Kalinske or IGN’s recent article on the history of Sega, you’ll know that the man has a pretty good memory. Mike Latham also comments about this. “So, there was never any product discussed with him after Moonwalker,” he says, “and after the MC Hammer debacle and some nearly-avoided others, the company tended to shy away from the music business for licensing sources. Also the Sega Music label really soured the company on the music business.”

Thus, one has to wonder why Roger Hector would remain silent about such star power being added to such a major release’s development. He didn’t tell Latham, who was heading game testing at the time and had been present at the meetings about the game. He didn’t tell Pam Kelly, who was in charge of the game’s marketing or Bill White, Sega’s VP of marketing at the time, and he didn’t tell Tom Kalinske, president of the company’s American branch. Who then, did he tell? Surely someone at the company, outside of STI, was aware that Michael Jackson, perhaps the most popular entertainer in the world at the time, was working on Sega’s flagship franchise. How does one keep such a thing a secret?

Another item that requires review is just how much of the music included can be directly attributed to Jackson. Most of the Sonic 3 pieces that are said to resemble Jackson’s songs are only comparable when heavily altered, such as being transposed up or down or having their tempo increased or decreased. People have also noted that the chord progression in some of the compared songs don’t match up or that some of them don’t even have the same number of chords. It’s more than likely that Cirocco and the others were influenced, as Drossin mentioned, by Jackson’s own work and wrote songs in the same vein. As they had direct access to his music, the team would have easily been able to sample and emulate songs not yet released commercially. Buxor’s earlier quote opens the door for this possibility by suggesting that Jackson could be quite hands-off in his music composition, and that could have been the case with Sonic 3. Such “inspiration” is quite common in the game industry, as evidenced by several other YouTube videos, such as this one which shows a clear comparison between REM’s “All the Right Friends” and Elecman’s theme from Mega Man. But wait! That song also sounds a lot like Journey’s “Faithfully!” Did Capcom plagiarize, or was it merely “inspired?” SNK was apparently inspired as well, when it composed “Spread the Wings” for Garou: Mark of the Wolves. The tune bears a striking resemblance (fifty-eight seconds in) to Robert Miles’ “Children.” I guess ID Software did the same then with the Doom soundtrack as well, right? Doom composer Robert Prince even admits to taking a cue from established commercial music: “I did not think that this type of music would be appropriate throughout the game, but I roughed out several original songs and also created MIDI sequences of some cover material.” What’s most notable about these comparisons is that no changes in pitch or tempo were required to see the similarities.

Another thing to consider is just how much of Sonic 3’s music Jackson actually did himself and what kind of use they had in and out of the game. While we know he was involved, not every song in Sonic 3 may have been turned into an song for use on one of his albums. Jackson wrote most of his biggest hits, like “Billie Jean, “Beat It,” and “Smooth Criminal” himself, so it’s doubtful that he would have to resort to sampling his own work from Sonic 3 for future albums, as he was more than creative enough to come up with new material on his own. All of the songs involved in this issue were written either before or during the time of Sonic 3’s development, which works against the argument that MJ sampled his own work from the game for later use. Remarkably, some even contend that “Smooth Criminal,” recorded in 1987, bears resemblance to “Ice Cap Zone, Act 1.” This suggests that Jackson sampled his own music, specifically a song written a full three years before the character Sonic the Hedgehog was even conceived, and one already used in a Michael Jackson game by Sega!

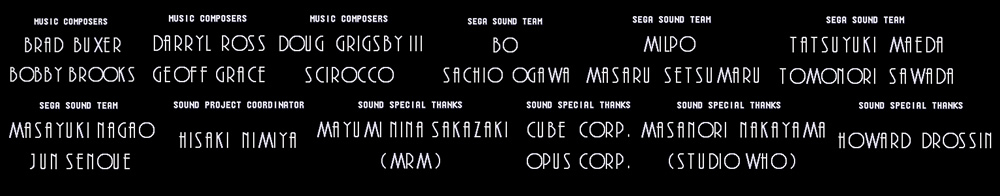

Here is the entire sound credit list for Sonic 3. Notice that neither Jackson nor a “John Jay Smith” of any type are present, and notice that Howard Drossin receives only a “sound special thanks.”

Click for a larger image!

What does this all mean? Most likely, that none of the music attributed to Jackson in Sonic 3 was actually done by him, but rather by others who tried to write music that sounded like his. Mike Latham told us about how widespread the practice of musical “inspiration” among game composers is, and even admitted to being a little inspired himself back during his development days. “I remember when I did Ghostbusters 2, I had no rights to the music and made near sound-alikes to all the songs. If you heard that title you would be sure I had the rights for the soundtrack songs, but I just did them in a slight style change.”

Mull It Over A Bit…

Given everything we’ve seen so far, let’s put this all in perspective, shall we? No matter how much people will favor or disfavor the contention, there are some pretty obvious items that go beyond the emails and forum posts. When one looks past all the quotes and sound bites, there are a few things that simply appeal to common sense and have to be mentioned. There seems to be more than ample evidence that the pop star was in some way involved with Sonic 3, but Sega-16 highly doubts that there was ever a contract signed or that anyone in management had ever even heard a presentation pitching the idea. Had any of that happened, there would have been severe ramifications upon Sega’s severing ties with Jackson, in both a collaborative and legal sense. Here are a few of the most prominent questions that would have been raised:

- Can you imagine Sega “firing” Michael Jackson? Moreover, can you imagine someone as popular as Jackson working with the leader in 16-bit hardware of the time, and not a smidgen of advertising emerging from such a tandem? Sonic 3 was released in 1993. Sega had released several versions of Moonwalker only three years before, and it hyped the hell out of all of them. Jackson’s scandals hadn’t occurred when Sonic 3 began development, so one might think it odd that the most popular entertainer in the world is scoring the soundtrack of Sega’s flagship franchise, and there isn’t a mention of it ANYWHERE in any of the advertising. The Chandler scandal didn’t make the news until three months before Sonic 3 shipped. How would Sega have missed the boat on promoting Jackson’s involvement with such an important game, when it had absolutely no reason to do so at the time?

- Sega didn’t want Jackson but wanted his music? Confirming his involvement would mean that Sega canned the entirely original score he was working on because it was terrified of the bad publicity, but for some reason it decided to leave in songs that sounded very much like music Jackson was releasing commercially. Kill the original score and leave in the imitations? Moreover, after being terminated by Sega, does anyone think Jackson would let it include songs that sound just like his in the very game from which he was just fired? Additionally, the lack of a formalized contract would have presented serious legal issues for Sega had it used his work without written permission.

- Jackson would have been recycling music from a video game. If it’s true, then Jackson went on and took music he originally scored for a Sonic game and reworked them for future albums, where they eventually became “Stranger in Moscow” and “Blood on the Dance Floor.” He basically got fired from Sega, but he used music that was for its game for himself? Jackson was more creative than that. Chances are that any music done for Sonic 3 but used for Jackson’s own music came from Buxor and other musicians imitating Jackson’s style and not by the Gloved One himself.

- There was no reason for Sega of Japan or Europe to change Sonic 3’s music. The Chandler scandal had little international effect, and Jackson’s possible sexual exploits with a child wouldn’t have been news to a country such as Japan, which didn’t outlaw such activities until 1999. What motive would SOJ and SOE have had to rescore the entire game only five months before its release date, especially when doing so could have delayed it in those territories? The Mega Drive in Japan was in need a major titles, and none was larger for Sega than Sonic. The thought of a game in the series with Jackson’s name attached would have produced major publicity for the slow-selling console there, and SOJ would have had no reason at all not to push the tandem.

- If the score was altered, why cherry pick which songs would be used? Assuming that Jackson was taken off development, why use his songs at all? Roger Hector mentions that “his work was dropped” but people believe several of his songs were remixed by others, and that these were then reworked by Jackson himself into pieces for later albums. Why would Sega do that? If you’re going to fire the guy, why keep any part of his work? And if you’re going to keep songs, why not just use the actual, finished score?

- Sega’s own management debunks the rumor. We have a senior producer, SOA’s marketing director, and its president all mentioning that nothing was ever written up between the company and MJ. This doesn’t mean he never worked on anything; it just means that it was never put into contract. From a legal standpoint, this means that the possibility of Jackson’s compositions making their way into Sonic 3 in any form are quite slim, and in turn it supports the whole “inspiration” theory.

So What’s the Verdict?

When all the data is added up, there is no conclusive proof that Jackson had anything to do with Sonic 3 outside of Roger Hector, Howard Drossin, and Cirocco’s testimony. No documents have surfaced, no actual tracks, no betas with his name in it – nothing. On the other hand, nothing conclusive has surfaced to the contrary either. We have several accounts that nothing was ever made official, but they say nothing about whether or not Jackson actually composed music and, if so, how much. Again, none of this truly proves anything, to be sure, but it does bring up some interesting points. For what it’s worth though, we can’t see someone as prominent as Jackson entering into an agreement with Sega in virtual anonymity or being nice enough to let Sega use his music after he was fired.

We also have to wonder about the utter silence of those involved at the time. Surely, something this big would have been announced with bells and whistles, and management having no idea of it leads us to believe that Jackson’s involvement wasn’t an official one. Sega-16 has absolutely no reason to doubt Roger Hector’s word, as he has contributed to several articles for the site, and his information has always been spot-on. Both he and Kalinske put Jackson at Sega during this period, talking with game designers, which heavily suggests that something was being done, at least informally. Most likely, Hector was going to pitch the idea to his superiors once a complete score had been done and enough of the game was ready to be shown (similar to how Peter Morawiec worked on his Sonic-16 game alone until it was ready to be shown). Hector’s own statement that he had the only copy of the finished soundtrack on cassette supports this, as does Cirocco’s email about possessing demo versions of the songs. If Jackson had actually been hired by Sega, why would Hector, and not someone like Bill White or Tom Kalinske, have the only copy of his work, unless its existence had yet to be brought to their attention?

Morawiec even mentions in our interview that he had to periodically produce content for management. “We were moved to a fancy SOA campus in Redwood Shores, and suddenly we had to put on presentations in front of a whole slew of executives and marketing people, etc.” How then, would Kalinske and the other executives be totally unaware of what was most likely the biggest news surrounding the most important STI project of them all? Is it possible that Jackson’s public profile went south just before his work was to be shown, and Hector was forced to sweep the whole ordeal under the rug?

Morawiec even mentions in our interview that he had to periodically produce content for management. “We were moved to a fancy SOA campus in Redwood Shores, and suddenly we had to put on presentations in front of a whole slew of executives and marketing people, etc.” How then, would Kalinske and the other executives be totally unaware of what was most likely the biggest news surrounding the most important STI project of them all? Is it possible that Jackson’s public profile went south just before his work was to be shown, and Hector was forced to sweep the whole ordeal under the rug?

Sega itself seems to love hinting about the situation without confirming or denying anything. The most recent example of this comes in the Sonic 3 museum section of Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection, released in 2009 for both the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3. The final trivia note reads “Sonic 3’s musical score was originally going to be composed by Michael Jackson.” Lamentably, it doesn’t mention whether or not this was an idea that was scrapped, an unofficial collaboration, or an actual contractual agreement. Neither does it refer to any music actually being scored by MJ and used or discarded by Sega.

For these reasons, though the evidence seems compelling, we’re reluctant to concede that anything official was ever established between Sega and Michael Jackson. That doesn’t mean, however, that Jackson never had any involvement at all. Our theory is that whatever work he did was off the books, and any chance of any of it ever been green-lighted by Sega management was killed as soon as the Chandler case broke. The two powerhouses had a history together in both the arcade and on the Genesis, and they would work together again on Space Channel 5 for the Dreamcast. This shows that Sega of America hadn’t blacklisted Jackson after his 1993 scandal, but a desire to distance itself from him for a while is not only understandable, it’s just plain common sense.

There’s no denying that there’s something there, something certain people perhaps either cannot or do not want to comment on, but the fact that even Tom Kalinske himself has no knowledge of contract being signed is pretty hard evidence of nothing solid ever coming out of such collaboration. Only time will tell the true story and cement it as fact or dispel it as another urban legend. Our readers will no doubt reach their own conclusions based on the facts presented, and this discussion will continue to go on across the Internet. Should anything come out either way, we’ll be here to report it. Until then, play your copy of Sonic the Hedgehog 3 and think of what may be…

This article was updated on March 31, 2025.

Sources

- Behind the Scenes: Sonic The Hedgehog 3 and Sonic & Knuckles. GamesTM. September, 2007.

- Campbell, Lisa (1995). Michael Jackson: The King of Pop’s Darkest Hour. Branden.

- Doree, Adam. Interview with Yuji Naka. Kikizo. February 4, 2009.

- Fahs, Travis. Interview with Tom Kalinske. IGN. 2009.

- Hagues, Alana. (2022, June 9). “Brad Buxer Reconfirms Michael Jackson’s Involvement with Sonic 3’s Soundtrack.” Nintendo Life.

- Hector, Roger. “RE: Question about Sonic 3 Soundtrack.” Email to Ken Horowitz. March 20, 2008.

- Horowitz, Ken. Interview with Al Nilsen. Sega-16. March 11, 2008.

- ————-. Interview with Peter Morawiec. Sega-16. April 20, 2007.

- Interview with Howard Drossin. Sonic Retro. August, 2008.

- Interview with Roger Hector. Secrets of Sonic Team. August 31, 2005.

- Kelly, Pamela. “Re: Article on Sonic 3 & Michael Jackson.” Email to Ken Horowitz. May 12, 2008.

- Latham Mike. “Quick Feedback.” Email to Ken Horowitz. March 14, 2008.

- ————. “RE: Quick Feedback.” Email to Ken Horowitz. March 15, 2008.

- McFerran, Damien. Retrospection: Mega CD. Retro Gamer Magazine. April, 2009.

- Sazpaimon. Jackson vs. Sonic 3. Sonic Cult.

- Sonic The Hedgehog 3 Museum Trivia. Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection (Xbox 360 version). 2009.

Pingback: Video Game Analysis – Generations

Pingback: More Fuel For The Michael Jackson Sonic 3 Conspiracy Theory | Kotaku Australia

Pingback: Michael Jackson y la música de Sonic 3: mito o realidad — HombreImaginario