In the early nineties, arcades were full of walk-and-punch “twitch” games, where players would walk from left to right across the screen and beat up hoards of weaker enemies before fighting the harder boss. These games used two or three buttons, a joystick and required little skill or practice to win. They were called twitch for this reason, one only had to hit the buttons fast enough for success. The most popular of which was Capcom’s Final Fight, featuring the latest graphics and sound. These were not the only games in the arcade, of course. The simulator game was also popular with titles like Sega’s Afterburner, Hang-On, and Outrun. Shooters, also twitch games, where players control characters that blow away screens full of enemies with big guns, were popularized by games like R-type and Mercs. Pinball was still an arcade staple as well. It was among these games that the seeds of Street Fighter II were sown.

Developer History

The man behind the Street Fighter franchise is one of the true legends in gaming, and although he doesn’t get the type of recognition others like Shigeru Miyamoto and Yu Suzuki do, Yoshiki Okamoto deserves to be placed on their level. Gamers automatically associate his name with Capcom’s seemingly eternal franchise, but his portfolio goes far beyond that. He has been responsible for some of the most classic coin-ops ever made, like Gun.Smoke, 1942, and Gyruss; as well as console hits like Resident Evil & Power Stone.

The man behind the Street Fighter franchise is one of the true legends in gaming, and although he doesn’t get the type of recognition others like Shigeru Miyamoto and Yu Suzuki do, Yoshiki Okamoto deserves to be placed on their level. Gamers automatically associate his name with Capcom’s seemingly eternal franchise, but his portfolio goes far beyond that. He has been responsible for some of the most classic coin-ops ever made, like Gun.Smoke, 1942, and Gyruss; as well as console hits like Resident Evil & Power Stone.

Born in Ipponmatsu Town, Japan, in 1961, Okamato was hired right out of college as an illustrator by Konami. His first assignment was to do the poster for Tutankhamen, but he eventually found himself making games. He deceived his superiors (they thought he was working on a driving game), and created a flying game instead, which was called Time Pilot. It was a huge success, and he left Konami in 1983 to work for Capcom, where he churned out some of the biggest games in history. In 2003, Okamoto headed off on his own, forming Game Republic. He continues to innovate and has recently announced several titles in production for the Playstation 3 and Xbox 360.

The Games

The original Street Fighter was released in 1987 to a small niche market. It featured two young karate students, Ken and Ryu, who would travel the world in a tournament to be the strongest fighter. Players could select either one and control them to fight the computer or another player using an array of punches, kicks, blocks, and secret “special” attacks. The goal was to use these attacks and defenses to either hit the enemy until their life bar was depleted (KO) or have the fullest life bar when time ran out. Combat was divided into rounds, and a battle would consist of the best two out of three rounds. Other games of this type were around, but none were particularly popular; there were several hybrids that played one-on-one as well as standard walk-and-punch. Quite popular in arcades, Street Fighter was ported to NEC’s fledgling Turbo Grafx-16 CD-ROM System a year later, with a name change. The game was now called Fighting Street.

When Street Fighter II was released, it appealed to many as the first game of its type. As Horowitz (ed. note: not me!) says, “Street Fighter II did not create a genre. It defined and popularized one that had its origins in Karate Champ, Yie Ar Kung Fu, and Street Fighter itself.” Developed by a team led by Yoshiki Okamoto, Street Fighter II was going to be something new and different. It was using Capcom’s CPS board, the latest technology. Where other fighting games had relatively bland graphics, Street Fighter II had vivid colors, sharp resolution, detailed backgrounds, large characters, and more animation than ever before. The CPS board brought better sound as well. Voices were digitized from real people and used much more than previous games. Moreover, the music was crisper and more real, and the control was tighter with the new technology. Previous fighting games could not accurately process the input needed for such rapid action, which led to many moves executed by luck without any consistency. With Street Fighter II, the CPS board checked the joystick constantly, and inputs were recorded and executed properly, this time with consistency. The control scheme itself was also new. The average game at this time used two buttons and a joystick, but Street Fighter II used six buttons and a joystick. And its final, true innovation – the ability to select from a cast of individual, original characters. All these advanced features gave the player a new sense of realism and involvement with the game. Players no longer could get by with random button smashing. Success arose from skill and practice, not luck. This is what brought Street Fighter II to the front, and why people had never seen a game like it before.

The first version of Street Fighter II has the honor of being the only fighting game after 1991 not to be called a “Street Fighter clone.” It featured the return of Ken and Ryu, and introduced the oft-copied characters Chun-Li, Guile, Blanka, E. Honda, Dhalsim, and Zangief. A player would select one of the eight world warriors and enter the tournament held by the mysterious organization known as Shadoloo, or sometimes referred to as “Shadowlaw,” depending on the source. The tournament consisted of fighting the other seven competitors and then the four “bosses”. These bosses were Balrog, Vega, Sagat, who was the final opponent in the first Street Fighter, and M. Bison. The bosses were not selectable, which led to many rumors of codes that would access them. After defeating all the opponents, the game ended with a few animations and text telling the character’s story, then a roll of the credits.

With better controls and technology than ever before, old features got reworked into a new game. The special move was perfected in Street Fighter II. A special move is an attack or sometimes a defense that requires a special button and joystick combination to execute. Special moves had been present in the first game, but were too difficult to do and did too much damage. Special moves in Street Fighter II were something that a player could do better with practice and complement their arsenal of standard moves. The ability to block attacks was also an idea that finally worked in Street Fighter II. To block is be hit by an attack but not be damaged, or at least not take full damage. Few other games used any find of blocking feature and for those that did, it rarely worked properly.

In between smashing opponents, the player could take a crack at a bonus round. Bonus rounds or bonus stages were mini-games that tested speed or precision. In Street Fighter II, there were three bonus stages – smashing a car, breaking falling barrels, and clearing flaming barrels.

Capcom had a bona-fide smash hit on their hands, and quickly capitalized on its popularity. The game was eventually ported to the SNES, to incredible sales and the envy of Genesis owners everywhere.

Street Fighter II was played so much that glitches began to surface. Some of these glitches were removed, while others were left in because they actually improved game play. The most important glitch was not so much a bug, but rather a programming oversight. This error allowed players to interrupt the animations of one move with another different, usually special move. The two to three moves would string together and could not be blocked after the first hit. These techniques became known as combos and were entirely new to gamers. The goal now was to find and master the hundreds of combos possible. Combos would become a necessity of the fighting game genre, and a staple of the Street Fighter II series.

With the runaway success of Street Fighter II, Capcom was flooded with requests to improve various aspects of the game. In one of the first times a game company responded so fully to player requests, Champion Edition was released. The game was not so much a new chapter in the series, but rather an upgrade, using the same tournament premise as before with the once unselectable bosses now fighting as combatants. Topping the list of new features was the ability to play characters against themselves, since in Street Fighter II, two players could not choose the same character, which lead to uneven matches. Champion Edition also introduced new costumes for characters, to allow same character fights and prevent confusion of which player controlled which character. With this feature, the fight would be based more on player skill, not who could select the better character first. Also new was the introduction of boss characters as playable. They were toned down in power from their previous incarnations to even out fights, but they still maintained something of an edge. Gameplay was sped up slightly, and background settings were altered to reflect a different time of day. Returning characters were given slight upgrades as well. Ryu and Ken, who had previously been the exact same as far as ability, were given slightly different speeds, ranges, and damages for their special moves. The rest of the cast was altered in the same manner to balance strengths and weaknesses, but there still remained particular dominant characters. A few new animations were added, character endings were altered slightly, and bosses were given the same ending animations with varying text.

With the runaway success of Street Fighter II, Capcom was flooded with requests to improve various aspects of the game. In one of the first times a game company responded so fully to player requests, Champion Edition was released. The game was not so much a new chapter in the series, but rather an upgrade, using the same tournament premise as before with the once unselectable bosses now fighting as combatants. Topping the list of new features was the ability to play characters against themselves, since in Street Fighter II, two players could not choose the same character, which lead to uneven matches. Champion Edition also introduced new costumes for characters, to allow same character fights and prevent confusion of which player controlled which character. With this feature, the fight would be based more on player skill, not who could select the better character first. Also new was the introduction of boss characters as playable. They were toned down in power from their previous incarnations to even out fights, but they still maintained something of an edge. Gameplay was sped up slightly, and background settings were altered to reflect a different time of day. Returning characters were given slight upgrades as well. Ryu and Ken, who had previously been the exact same as far as ability, were given slightly different speeds, ranges, and damages for their special moves. The rest of the cast was altered in the same manner to balance strengths and weaknesses, but there still remained particular dominant characters. A few new animations were added, character endings were altered slightly, and bosses were given the same ending animations with varying text.

Genesis owners were delighted to receive Champion Edition in 1992, as it was a leg up from the original SNES game. The new modes were a big hit, and the game played like a dream with Sega’s new six-button controller. Not as colorful as the SNES release, and with some scratchy voice work, it was still a great coup for Sega. It was now SNES owners’ turn to be envious.

The Rainbow Edition of Street Fighter II represented not one single game, but a host of games that popped up in arcades after the release of Champion Edition. These games came about because of features players felt had been overlooked in Champion Edition. Not endorsed or produced by Capcom, the Rainbow Edition was created by various programmers who hacked the ROMs of Champion Edition and edited the game as they saw fit. What resulted was a game that took Street Fighter II to a level of gameplay so furious, it was nearly unplayable. New features included special moves which were excessively fast or traveled too far and the ability to perform any special move while jumping, something never before seen in the Street Fighter series. Certain characters have special moves that are categorized as “fireballs”, which are projectile attacks. Fireballs are thrown by Ken, Ryu, Guile, Dhalsim, and Sagat and are followed by the character delaying, which allows only one shot at a time. In Rainbow Edition, every character was given the ability to toss a fireball and the after-fire delay was removed, allowing multiple fireballs at once. Another popular feature was the ability to change characters mid-fight. Previously, players would select their character prior to the fight and keep that character until the contest was over. Pressing the start button at any point in the game would cycle to another character. Despite these very interesting features, games of this type were not particularly popular because of their wild nature. Special moves were too fast and because the game was made by hackers instead of actual Capcom programmers, it would glitch and crash frequently.

Not particularly happy with people hacking their games, Capcom gathered the best features of Rainbow Edition and released a new upgrade, Turbo: Hyper Fighting. Many fans considered this game to be the apex of Street Fighter II gameplay. There was no change in the story line from Champion Edition; it was still the same tournament. This version’s most immediate upgrade was the large increase in game speed. Some special moves were altered so that they could be performed while jumping, like in Rainbow Edition. Other features pulled from the hacker’s game included special moves that went faster and farther, but not to such an extent, and Chun-Li’s new ability to throw a fireball. Many other characters were given completely new moves as well, such as E. Honda and Blanka, who could now perform diagonal versions of their older special moves. Despite the introduction of new attacks, no new character animations were added; programmers just altered the existing ones. Character strengths were again altered to even fights and new costumes replaced the ones used in Champion Edition. The bosses were also given real ending animations instead of the hastily added scrolling text of the previous version. With this game, Capcom felt that it had finally properly addressed player requests.

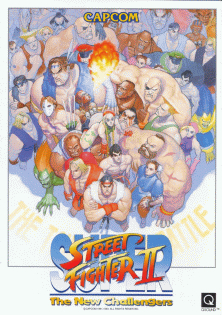

When Turbo‘s popularity began to wane and rumors circulated of Street Fighter III, Capcom released a new upgrade to the series. This installment introduced the new CPS2 board, a large step up from the now several years-old CPS board of the previous games. Gamers were now greeted with an entirely new introductory sequence in which a large animated Ryu tossed a fireball at the screen. This anime-styled cinema was a welcome change from the bland animation of one guy knocking out another guy in front of a building.

Super also featured four entirely new characters; Cammy, Fei Long, T. Hawk, and Dee Jay. The story was updated to include these extra fighters, but remained largely unchanged from the tournament held by Shadoloo. Returning characters were given more special moves, and this time additional animations to go with them. Standard attacks were given new animations as well. These were most prevalent in the bosses, who had a very limited set of frames from the earlier games. Backgrounds were updated to match the standards set by the new challenger’s stages, and many more colors were possible because of the CPS2 board, as was reflected in the bright, vibrant graphics. Where previous games had the option of two costumes per character, Super had eight. This game also introduced Capcom’s new Q-sound technology. All the voices and sound effects were sampled again and presented in higher quality, and background music was remixed with better synthesizers, giving a much more realistic sound. Super introduced the combo-counter system, which told players when they did a combo, how many hits it made, and awarded points based on damage. Combos became longer, now averaging four hits as opposed to the previous three. Bonuses were given to award getting the first hit in a round and counter-attacking the opponent. Despite all these new features, Super Street Fighter II failed to draw the crowds of previous games. Many were turned off by the slower game play, on par with Champion Edition speed. And almost all players had become jaded after so many upgrades and the slew of Street Fighter clones saturating arcades. The public wanted Street Fighter III.

Even so, the game was ported to several home consoles, including the Genesis and SNES. Though it is a full eight megs larger on Genesis (40 megs in all, the largest Genesis cart ever made), it is generally acknowledged that the SNES version is the superior of the two, due to its cleaner graphics and sound. Still, it plays wonderfully on Sega’s console, and is a testament to just how much could be achieved on the supposedly “inferior” hardware.

Capcom did not release Street Fighter III, instead they threw another upgraded into the flooded market. Claiming that Super was rushed and did not have all the features they wished to include, the company said Super Turbo was what Super should have been. The opening sequence featured Chun-Li, Cammy, and the new boss, Akuma, spliced in with Super‘s Ryu. Game play was sped up from Super, the bonus rounds were removed entirely, and computer controlled players were much more difficult. This was the first Street Fighter game to use “Super Combos” and the “Super Meter.” Super Combos were stronger, flashier versions of special moves, and they were executed with more complex motions than other special moves, requiring the use of the Super Meter. The Super Meter was a gauge at the bottom of the screen that filled a little with each attack. When filled, a player could empty the meter with a Super Combo. These moves were added as a kind of last-ditch desperation attack that could turn the tide of a round or seal a victory. Almost every character received some kind of new attack as well, whether it was a special move or standard punch or kick. The juggle combo- a combo performed while one or both players was off the ground- was introduced in Super Turbo. Another new feature was the overhead hit, an attack used to hit even when the opponent blocks. With the most balanced characters in the series, these gameplay tweaks opened new levels of strategy and offered the chance for drastically different techniques.

Akuma, the ultimate opponent made his first appearance in Super Turbo. Only by completing the game without losing and using a certain number of Super Combos could a player meet their end at the hands of Akuma. He was selectable through a secret code, but the version players used was much weaker. Special ending animations were added for players who used or could defeat Akuma. All other character’s endings were enhanced with an extra graphic that added to their story. Like Super, Super Turbo was met with lukewarm appreciation. Although it was the end of the Street Fighter II series, Street Fighter III was still several years away.

Street Fighter III was finally released, but not immediately after Super Turbo. Capcom stalled with a new series of games that brought back characters from the original Street Fighter as well as introducing many new ones. Known as Street Fighter Zero in Japan and Alpha in the U.S., this game used entirely new graphics and incorporated many new features. Quite popular, the series went through several installments and upgrades as well, and saw home ports to the Sega Dreamcast and Playstation.

During this time, a game based on the Street Fighter movie was made. It used digitized images of the actors from the motion picture and played very similarly to Alpha. However, it’s graphics were rather bland and the game did poorly. Yet another twist was added to the formula with Street Fighter EX. This time the game switched from 2D sprites to 3D polygons. Again, it played like Alpha, but introduced more new characters than previous games. Somewhat popular, an upgrade and a sequel were made. Other games featuring the Street Fighter universe were Puzzle Fighter, a Tetris-type game showcasing super-deformed (big head, small body) versions of popular characters, and Gem/Pocket Fighter a fighting game using the child-like forms from Puzzle Fighter. There were also the cross-over games of X-men Vs. Street Fighter and Marvel Vs. Capcom that featured popular Street Fighter characters.

During this time, a game based on the Street Fighter movie was made. It used digitized images of the actors from the motion picture and played very similarly to Alpha. However, it’s graphics were rather bland and the game did poorly. Yet another twist was added to the formula with Street Fighter EX. This time the game switched from 2D sprites to 3D polygons. Again, it played like Alpha, but introduced more new characters than previous games. Somewhat popular, an upgrade and a sequel were made. Other games featuring the Street Fighter universe were Puzzle Fighter, a Tetris-type game showcasing super-deformed (big head, small body) versions of popular characters, and Gem/Pocket Fighter a fighting game using the child-like forms from Puzzle Fighter. There were also the cross-over games of X-men Vs. Street Fighter and Marvel Vs. Capcom that featured popular Street Fighter characters.

It was in 1997, three years after the release of Super Turbo and six years after Street Fighter II, that Capcom finally unveiled the third game. Street Fighter III: A New Generation featured the new CPS3 board, an almost entirely new cast and slightly deeper gameplay than before. The game received two updates: Double Impact & Third Strike. Both came home to consoles, and while the Dreamcast version played well enough, fans finally got a true version in 2004’s Street Fighter Collection for PS2 and Xbox.

Still Fighting after All These Years

Other fighting games, such as Tekken and Virtua Fighter, have competed with Street Fighter in a changing arcade environment which has seen the traditional 2D fighter slowly fade into the background. Even 2D stalwarts like SNK’s King of Fighters series has gone 2D. Today, arcades have fewer of these games and instead offer large simulators and redemption games, and the market for one-on-one fighters has come home with high-tech consoles like Playstation and Xbox. Capcom may continue to make new Street Fighter games and updates, but the glory of the series remains with the original.

Capcom’s recent announcement that a fourth entry in the franchise is in the works has met with mixed reactions from fans. Will it be 2D, or take the 3D route of most modern brawlers? Only time will tell if Capcom can breathe new life into a property that was once undisputed champion.

The complete release chronology is as follows:

- Street Fighter, Arcade (1987)

- Fighting Street, Turbo Grafx-16 CD-ROM (1988)

- Street Fighter, IBM PC (1988)

- Street Fighter, Timex/Sinclair 1000 (1988)

- Street Fighter, Atari ST (1988)

- Street Fighter, Commodore 64/128 (1988)

- Street Fighter, Amiga (1988)

- Street Fighter 2010: The Final Fight, NES (1990)

- Street Fighter II: The World Warrior, Arcade (1991)

- Street Fighter II: Champion Edition, Arcade (1992)

- Street Fighter II, SNES (1992)

- Street Fighter II, X68000 (1992)

- Street Fighter II: The World Warrior, IBM PC (1992)

- Street Fighter II: Hyper Fighting, Arcade (1992)

- Street Fighter II, Commodore 64/128 (1992)

- Street Fighter II, Timex/Sinclair (1992)

- Street Fighter II, Atari ST (1992)

- Street Fighter II, Amiga (1992)

- Super Street Fighter II: New Challengers, Arcade (1993)

- Street Fighter II Turbo, SNES (1993)

- Street Fighter II Special Champion Edition, Genesis (1993)

- Street Fighter II Champion Edition, PC-Engine (1993)

- Super Street Fighter II Turbo, Arcade (1994)

- Super Street Fighter II, Genesis & SNES (1994)

- Super Street Fighter II Turbo, 3DO (1994)

- Super Street Fighter II Turbo, PC CD-ROM (1995)

- Street Fighter II, Game Boy Color/Super Game Boy (1995)

- Street Fighter the Movie, Arcade (1995)

- Street Fighter the Movie, Saturn & Playstation (1995)

- Super Street Fighter II, PC CD-ROM (1995)

- Street Fighter Alpha: Warriors Dreams, Arcade (1995)

- Street Fighter Alpha, IBM PC (1995)

- Super Street Fighter II, Amiga (1995)

- Street Fighter Alpha, Saturn & Playstation (1996)

- Street Fighter Alpha 2, Arcade (1996)

- Street Fighter Alpha 2, IBM PC (1996)

- Street Fighter Alpha 2, Saturn & Playstation (1996)

- Street Fighter Alpha 2, SNES (1996)

- Street Fighter EX, Arcade (1996)

- X-Men vs. Street Fighter, Arcade (1996)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo, Arcade (1996)

- Street Fighter III: New Generation, Arcade (1997)

- Super Gem Fighter Mini Mix (Pocket Fighter), arcade (1997)

- Street Fighter EX Plus, Arcade (1997)

- Street Fighter II, Sega Master System (1997)

- Street Fighter Collection, Saturn & Playstation (1997)

- X-Men vs. Street Fighter, Saturn (1997)

- Street Fighter EX Plus Alpha, Playstation (1997)

- Marvel Super Heroes vs. Street Fighter, Arcade (1997)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo, Saturn (1997)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo, Playstation (1997)

- Super Gem Fighter Mini Mix (Pocket Fighter), Saturn (1998)

- X-Men vs. Street Fighter, Playstation (1998)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3, Arcade (1998)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3, IBM PC (1998)

- Street Fighter EX2, Arcade (1998)

- Street Fighter III 2nd Impact: Giant Attack, Arcade (1998)

- Street Fighter Collection 2, Playstation (1998)

- Marvel Super Heroes vs. Street Fighter, Saturn (1998)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II Turbo, PC (1998)

- Marvel Super Heroes vs. Street Fighter, Playstation (1999)

- Street Fighter III 3rd Impact: Fight for the Future, Arcade (1999)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3, Saturn & Playstation (1999)

- Street Fighter EX2 Plus, Arcade (1999)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3, Dreamcast (2000)

- Street Fighter EX2 Plus, Playstation (2000)

- Street Fighter III: Double Impact, Dreamcast (2000)

- Street Fighter III: Third Impact, Dreamcast (2000)

- Street Fighter EX3, Playstation 2 (2001)

- Street Fighter Alpha, Game Boy Color (2001)

- Super Street Fighter II: Turbo Revival, Game Boy Advance (2001)

- Super Street Fighter II X for Matching Service, Dreamcast (2001)

- Street Fighter Zero 3 Upper, Arcade (2001)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II X for Matching Service, Dreamcast (2001)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3, Game Boy Advance (2003)

- Hyper Street Fighter II: The Anniversary Edition, Playstation 2 (2003)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II, GBA (2003)

- Street Fighter Anniversary Collection, Xbox & Playstation 2 (2004)

- Street Fighter Alpha Anthology, Playstation 2 (2006)

- Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max, Playstation Portable (2006)

- Street Fighter II Special Championsip Edition, Xbox 360 [Live Arcade] (2006)

- Super Puzzle Fighter II: Network Battle, Mobile Phones (2006)

- Street Fighter IV, ??? (???)

Sources

- 100 Best Games of All Time. Electronic Gaming Monthly. Nov. 1997: 100+.

- Biography, Yoshiko Okamoto. Otaku.

- “Future Fights: A Looking Glass Into Tomorrow’s Fighting Games. Electronic Gaming Monthly. March 1995: 90-93.

- Herman, Leonard, Jer Horowitz, and Steve Kent. The History of Video Games. Videogames.com. 2, Dec. 1999.

- Hodgson, David and Tom Cannon. Street Fighter Alpha 3. Gamer’s Republic. Aug. 1998: 60-61.

- Hoek, and Hunter. The Official Unofficial Street Fighter Website. Liquid Fist. 5 Feb. 1997. 1 Dec. 1999.

- Horowitz, Jer, et al. The History of Street Fighter. 1999. Videogames.com. 2 Dec. 1999.

- Kent, Steven. Yoshiki Okamoto: The Clown Prince of Gaming. Gamers Today.

- Kunkel, Bill. Player’s Guide to Martial Arts. Electronic Games. May 1994: 46+.

- Lantis, Kailu. Street Fighter Dictionary. 27 Aug. 1998. Street Fighter Scene. 1 Dec. 1999.

- Quan, Slasher. Super Street Fighter II: The New Challengers. Gamepro. Feb. 1994: 36.

- Quentin. Quentin’s Akuma HomePage. 10 Dec. 1999. Tripod.com. 14 Dec. 1999.

- Rox, Shin. Street Fighter EX+. Gamefan. Sep. 1997: 52-53.

- Street Fighter EX2. Gamer’s Republic . July 1998: 44-45.

- Street Fighter Gallery. Animemanga.com. 14 Dec. 1999.

- Super Street Fighter 2. Electronic Gaming Monthly. July 1994:128-131.

Recent Comments