If we can attribute the incredible growth Sega experienced during the early 1990s to a single factor, it would definitely have to be advertising. No doubt that Sonic The Hedgehog played a huge role, as did the string of excellent business decisions made by Sega of America presidents Michael Katz and Tom Kalinske, but none of these would have gone anywhere without a solid method of getting the message to the masses. What made the Genesis the item to own and Sonic the coolest character around was a concentrated marketing blitz that drilled itself into the minds of consumers and dominated both print and television media.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Sega’s 16-bit advertising is how effective it was through several consecutively different campaigns. Though the company had tried its hand at catchy phrases before, it wasn’t until the second generation of Genesis games arrived that it finally found its groove. Three separate marketing strategies defined the Genesis era and still ring in the ears of longtime gamers everywhere.

A Shot in the Dark

Before 1990, Sega had been trying to gain market share since launching the Master System five years before. It had moderate success at best, consistently being overshadowed by everything Mario. The Challenge will Always be There and Now There Are No Limits both carried the console and were featured in desperate attempts to make it attractive. The problem wasn’t thought to be the console itself, which was much more powerful than Nintendo’s NES (Sega had two extra years to develop the Master System), nor the style of the advertising. What most in the industry attributed to Nintendo’s astounding success was its ironclad grip on the market. With a share of more than 90% due to overbearing licensing agreements, Nintendo hardly felt threatened by Sega going into 1990, and in all honesty, why should it have? The NES had totally dominated the previous generation, and even against the 8-bit machine, the Genesis was barely making headway in the U.S. and doing even worse in its native Japan. No, it was NEC and the PC-Engine that Hiroshi Yamauchi felt would be the big contender this generation, and even that would take some time. For the present, Yamauchi was content to let his company ride the success of its aging hardware, as planning for the next generation Nintendo console was already well underway. As then-Nintendo of America Chairman Howard Lincoln said in a 1992 interview: Nintendo has surpassed Sega in unit sales already. 3rd party licensees are flocking to us. Sega isn’t a question.

Before 1990, Sega had been trying to gain market share since launching the Master System five years before. It had moderate success at best, consistently being overshadowed by everything Mario. The Challenge will Always be There and Now There Are No Limits both carried the console and were featured in desperate attempts to make it attractive. The problem wasn’t thought to be the console itself, which was much more powerful than Nintendo’s NES (Sega had two extra years to develop the Master System), nor the style of the advertising. What most in the industry attributed to Nintendo’s astounding success was its ironclad grip on the market. With a share of more than 90% due to overbearing licensing agreements, Nintendo hardly felt threatened by Sega going into 1990, and in all honesty, why should it have? The NES had totally dominated the previous generation, and even against the 8-bit machine, the Genesis was barely making headway in the U.S. and doing even worse in its native Japan. No, it was NEC and the PC-Engine that Hiroshi Yamauchi felt would be the big contender this generation, and even that would take some time. For the present, Yamauchi was content to let his company ride the success of its aging hardware, as planning for the next generation Nintendo console was already well underway. As then-Nintendo of America Chairman Howard Lincoln said in a 1992 interview: Nintendo has surpassed Sega in unit sales already. 3rd party licensees are flocking to us. Sega isn’t a question.

Given how much Nintendo’s sales had increased since the NES exploded onto the scene in 1985, it was understandable that its creator would choose not to tinker with a successful formula. It employed a method of distributing its product to toy stores that was designed to permeate the industry, much to the chagrin of its competition. Over 10,000 World of Nintendo stores within retailers such as Toys ‘R Us and K-Mart, along with the massive distribution system it acquired when ally Worlds of Wonder (makers of Teddy Ruxpin) went belly up, allowed the company to more or less state its own terms. Children were asking for everything Nintendo in the late ’80s, and weary parents were giving in to their every demand. So confident was the House of Mario that it had the industry locked up, that it completely ignored exploring other age groups for possible market expansion. In early 1988, for example, discussions were held at Nintendo’s Richmond headquarters about broadening its audience to that beyond six-to-fourteen-year-old boys. One reason was to quell complaints from unsettled parents who were skeptical about video games. Bill White (director of advertising and public relations) and Peter Main (vice president of marketing) decided against it, however, believing that there was no need to “buy another demographic target.” They left this to other companies with whom they paired for promotions, like McDonald’s and Pepsi. Ironically enough, Bill White would end up at Sega under Tom Kalinske, where he would specialize in going after demographics outside the range Nintendo typically dominated.

Over at Sega however, Hayao Nakayama was singing a different tune. All his best efforts against the competition had been as effective as slinging acorns at a steel door. Deep down, he knew there was a way to beat Nintendo, as the agitated rumblings of its discontented third party base was increasing almost daily. Even Namco, the first ever NES licensee, had come within a hairsbreadth of all-out war with Yamauchi over its treatment with its renewal, and many other publishers were eager for another option. Sega now had the superior hardware; all it needed was that special something to make it take off in order to woo publishers over. Unbeknownst to Nakayama, the catalyst that would spark Sega’s meteoric rise to dominance would come from the most unlikely of all places: its tiny American branch. Japan was quickly becoming a lost cause, and only abroad could Sega gain the foothold it needed to truly compete against the NES. As the fall of 1989 approached, all eyes turned stateside.

Genesis Does…

When Michael Katz arrived at Sega of America as its new president in October of 1989, he found a tiny operation that sported less than fifty people and a daunting task laid out before him: make the Genesis a success. The new hardware had only launched a month earlier, and there had been several shifts in management in the previous four years, with company founder David Rosen now directly running the stateside operation. Katz was to report to him, and he quickly went about formulating a strategy that would get his company’s product noticed and hopefully chip away at Nintendo’s seemingly insurmountable lead. Nakayama would accept no less than a million units by the summer of 1990, so it was vital that Katz move quickly.

The Los Angeles branch of the New York ad agency Bozell had been given control of Sega’s $10 million advertising account in May of 1989, and had been responsible for the solid yet ultimately ineffective series of ads that presented each new Genesis game in the nation’s leading game magazines. Several titles were given star treatment in the months following the September launch, among them Golden Axe, Revenge of Shinobi, and Phantasy Star II. Though they focused on the strongest arcade and original offerings in the new line up, the Genesis Does It All and Your World Will Never Be the Same campaigns weren’t very successful in creating a shift in market share. Michael Katz knew that drastic measures had to be taken, and decided to kick things up a notch.

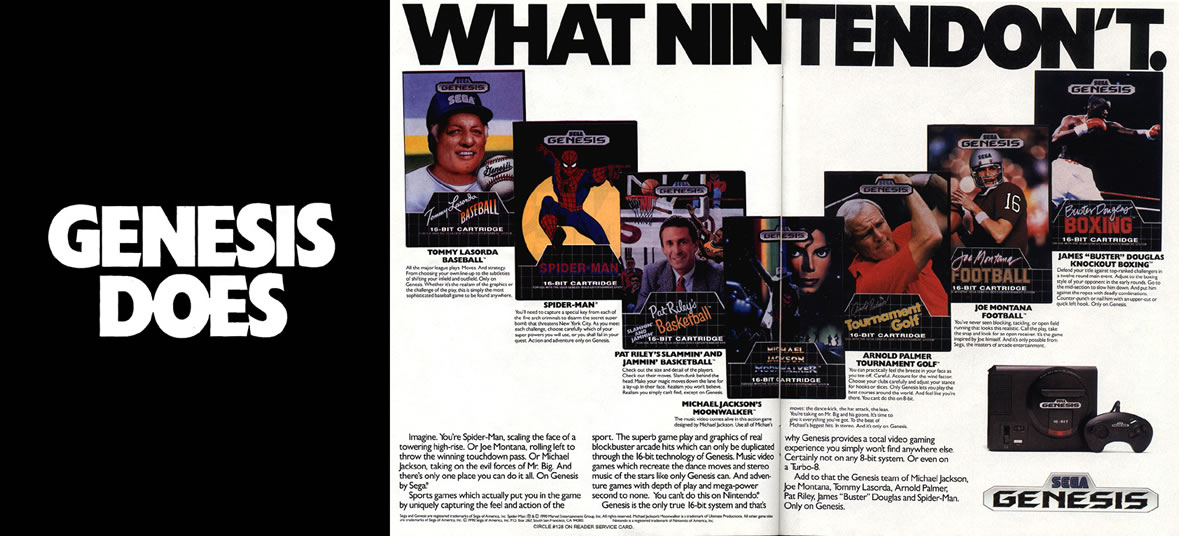

His first order of business was to beef up the American development of software (by 25-30% in the first year alone), namely in the sports category. Big names attracted lots of attention, and Katz knew that he could turn heads if the leading personalities of the day threw their support behind the Genesis. His plan was simple: entice American gamers with excellent sports titles developed in the U.S. and take Nintendo head-on, showing off the strengths of the new 16-bit hardware. After signing several major celebrities, like Joe Montana and Michael Jackson, Sega of America trained its marketing cannons at the Richmond-based giant that had dominated the market for half a decade.

Gamers of the era distinctly remember the brash and unflinching commercials and print ads. Genesis does what Nintendon’t not only filled magazines and televisions screens, it made an impression. Even Sega’s own executives were inspired by the new slogan. Former Head of Global Marketing Al Nilsen recalls “I remember when our ad agency went and promoted that for the first time to us, and when we heard the line Genesis Does What Nintendon’t, actually when we saw the line, because just seeing “Nintendo” with the apostrophe and letter T on the end was just so visually exciting, I think we just had this giant laugh.”

In the first six months of Katz’s tenure, Sega of America sold half a million Genesis units. Though it wasn’t a particularly large amount compared to the massive installed base the NES enjoyed (it was estimated at the time that there was a NES console in one out of every three American homes), it was a smashing start nonetheless. More importantly, Nintendo executives were beginning to notice the name Sega, despite Lincoln’s outspoken confidence.

What made the promotion so unique was its freshness and audacity. No one had ever referred to the competition by name before, and to do so in a mocking tone was simply unheard of. Ironically, few knew at the time that it heralded the coming of a new advertising age for Sega. No longer would it try to enamor gamers on the strengths of its titles alone. From this point on, Sega would tackle Nintendo face-to-face, focusing all its advertising on direct confrontation. After all, how would gamers know the Genesis was superior unless they were actually shown the difference? From the moment the first three-page ads appeared in Electronic Gaming Monthly and GamePro, it was clear that there was a marked contrast between the two competing platforms. A slew of titles were featured in the hard-hitting spots that directly pitted Sega’s offerings against the five year-old NES. Even NEC’s Turbo Grafx-16 took a hit in the very first one, being referred to it as a “Turbo-8” machine, in reference to its CPU.

What made the promotion so unique was its freshness and audacity. No one had ever referred to the competition by name before, and to do so in a mocking tone was simply unheard of. Ironically, few knew at the time that it heralded the coming of a new advertising age for Sega. No longer would it try to enamor gamers on the strengths of its titles alone. From this point on, Sega would tackle Nintendo face-to-face, focusing all its advertising on direct confrontation. After all, how would gamers know the Genesis was superior unless they were actually shown the difference? From the moment the first three-page ads appeared in Electronic Gaming Monthly and GamePro, it was clear that there was a marked contrast between the two competing platforms. A slew of titles were featured in the hard-hitting spots that directly pitted Sega’s offerings against the five year-old NES. Even NEC’s Turbo Grafx-16 took a hit in the very first one, being referred to it as a “Turbo-8” machine, in reference to its CPU.

As all this went on, Katz wasn’t content to sit back and watch things unfold; he took the ball and ran with it. In June of 1990, the very first issue of Sega Visions Magazine appeared, and gave gamers a single source for everything Sega. Though the magazine was nothing more than a simple marketing tool, Genesis owners didn’t care. It was theirs and a direct (though less extravagant) answer to Nintendo’s own Nintendo Power. Sega sweetened the relationship by rewarding owners with free games and accessories (like an extra controller and amplified stereo speakers) for their purchases. Master System owners were not forgotten either, as Sega offered them the Power Base Converter with which they could continue to enjoy their 8-bit favorites.

All the pieces were set. Sega’s brazen ads were beginning to gain steam, and Sega Visions served as a dedicated platform for solidifying the Genesis’ growing user base. Everything seemed to be going according to plan, and Michael Katz was pleased with what the fledgling American division had done. Unfortunately, Hayao Nakayama wasn’t so enthusiastic, and while the Genesis had surpassed his self-imposed goal of one million units, he was still troubled by Nintendo’s refusal to give up any market share. He felt it was time for a change in the U.S., and decided to replace Katz.

SEGA!!

To the tune of a modest profit and the successful establishment of the Genesis in the U.S., Michael Katz departed Sega in January of 1991. Replacing him was former Mattel president and Nakayama’s old friend Tom Kalinske (who had worked with Katz back at Mattel). Kalinske had already been at Sega of America for around three months before taking charge, assessing the situation and studying the domestic market, and he believed he knew what adjustments needed to be made. As president, he would ramp up Katz’s policy of direct competition to the nth degree, implementing several other changes. Slow and steady was not his approach, as he had demonstrated at Mattel. Like Katz before him, he felt that the only way to overthrow Nintendo was to take it on mano a mano, but he wanted to go a step further. Not content with merely naming his rival, Kalinske wanted to ridicule it. It was his belief that Sega could take advantage of those NES gamers that had begun to outgrow the hardware. They were looking for something more grown up, something that appealed to their new teenage outlook, and Kalinske wanted the Genesis to be that something. Sonic The Hedgehog had materialized at a particularly convenient moment and put Sega in a very unique position, as the Japanese software giant finally had the eyes and ears of the gaming industry focused in its direction. The audience was paying attention; now all Sega needed was to put on a convincing show. Kalinske knew exactly what to say.

The Genesis, not the NES, was the cool console to own.

He based his belief on several studies of the time on the entertainment habits of preteens and teenagers, including one done by advertising firm Goodby, Berlin, & Silverstein. Their account planning department, headed by director Irina Heirakuji, had conducted a study with around one hundred teens in their homes, analyzing what types of video games they enjoyed and purchased. The planners spent months combing through every aspect of their lives, filming what they said, and how they felt. The teens were studied both individually and in groups, and they were encouraged to invite their friends over to play. Researchers sat quietly, listening and watching what went on, and they later interviewed the participants about what they had observed.

It was no surprise that the majority of the participants owned a NES instead of a Genesis, since they were the generation that had been there at its launch in 1985 and had been loyal owners ever since. What Heirakuji and her planners did discover was that most of those who tried the Genesis agreed that they thought it was better overall. “There was this base level of dissatisfaction with Nintendo,” she remarked. “Not many kids had Sega, but they went to the homes of those that did. We knew that we would have to make Sega a cultural phenomenon if we were going to beat Nintendo,” Her assessment was clear. “We told Sega, ‘OK, if you’re going to bust it, now’s the time, because Nintendo is starting to react.’ ” Goodby, Berlin, & Silverstein then consulted with their creative department and initially came up with a pitch that had kids as master gamers and parents clueless as to what video games were all about. But two weeks before it was to be shown to Sega, focus groups slammed the commercials they were shown, citing that they made their parents look stupid and lacked any gameplay footage. The ads were then reworked and footage was included, and they were given a loud and in-your-face edge, which the focus groups loved. Michael Katz’s vision of slapping Nintendo in the face was about to become a punch in the gut.

It was no surprise that the majority of the participants owned a NES instead of a Genesis, since they were the generation that had been there at its launch in 1985 and had been loyal owners ever since. What Heirakuji and her planners did discover was that most of those who tried the Genesis agreed that they thought it was better overall. “There was this base level of dissatisfaction with Nintendo,” she remarked. “Not many kids had Sega, but they went to the homes of those that did. We knew that we would have to make Sega a cultural phenomenon if we were going to beat Nintendo,” Her assessment was clear. “We told Sega, ‘OK, if you’re going to bust it, now’s the time, because Nintendo is starting to react.’ ” Goodby, Berlin, & Silverstein then consulted with their creative department and initially came up with a pitch that had kids as master gamers and parents clueless as to what video games were all about. But two weeks before it was to be shown to Sega, focus groups slammed the commercials they were shown, citing that they made their parents look stupid and lacked any gameplay footage. The ads were then reworked and footage was included, and they were given a loud and in-your-face edge, which the focus groups loved. Michael Katz’s vision of slapping Nintendo in the face was about to become a punch in the gut.

The pitch was shown to Sega at the Redwood City (California) Holiday Inn, in a manner that would have made even the most tested of marketing executives twitch nervously. The ballroom had been set up to look like it was to host a small rock concert, complete with sound system by the same company that handled audio for the Grateful Dead and massive, towering screens. Goodby had chosen to go with a more non-traditional route for this presentation and showed the twenty or so Sega executives present things exactly the way their demographic saw them, without pie charts or graphs. The Sega representatives were blown away, and Goodby was awarded the account in July of 1992. Instead of a mere $10 million for advertising, the good fortunes of the previous year and a half allowed Sega to earmark $65 million in 1992 (they would allot $95 the following year), and the new agency was tasked with making the focus group response a national phenomenon. The American division was riding high on momentum in the U.S. and dominance in Europe, and now was the time to strike the fatal blow. Sega’s new ad agency would have two goals:

- Establish SEGA as the coolest brand for those between ages 10 and 14.

- Widen the consumer range from 10-14 years old to 10-27 years-old.

To say they were successful would be something of an understatement. Goodby produced thirty-five commercials in a four month period, airing them for the first time at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards. The ads were everything Kalinske had wanted, portraying Mario as yesterday’s hero and Nintendo as the company for children. Sega was here, it was now, and it was cool. Each of the ads blazed through the viewer’s mind, showing a mixture of game footage and shocking imagery. At the end of each video, one of the featured characters would glare into the screen and yell “SEGA!!” (the yell was actually voiced by writer and director Jimbo Matison). As the legend goes, a worker on the set of the first commercial suggested that someone scream the company’s name at the end of the commercial. It was a hit and subsequently incorporated into every ad in the series.

The Sega Scream was born.

So popular was the campaign that Tom Kalinske himself once commented about being backstage at a rap concert where no one knew him. As the rappers went on and off stage, they greeted one another with the Sega Scream. Not only had Sega’s message gotten through to gamers, it had now spread to become a part of popular culture itself.

Welcome to the Next Level

Although these famous words became synonymous with the Sega CD, they were actually first conceived during Goodby’s initial study back in 1992. It was decided that the Genesis would become the “next level” of gaming for those consumers who had outgrown Nintendo and its NES, and the slogan would symbolize that jump. Sega was at the forefront of a whole new generation of gamers, eager to carve out an identity for themselves. There was a massive transition underway in rock music, hip hop was making major strides in establishing itself as a bona fide genre, and even television, with shows such as Beavis & Butthead, was heading off in its own new direction. As Mitchell Stevens wrote in the April 25, 1993 edition of the Washington Post:

“Consider, for another example, a commercial for the Sega video game system. This ad is only 30 seconds long, yet it manages to hurl at the viewer 48 different images, including: a roller coaster, a rocket, a fireball, a touchdown, a rock concert, a collapsing building, an exploding house, a woman in a bikini (for that part of the audience that prefers such sights to house explosions), and a couple of dozen scenes from Sega video games themselves. That’s an average of 1 1/2 images per second, making this perhaps the fastest half minute in television and — what? — five, 10 times as fast as anything we are likely to see elsewhere in our lives.”

Welcome to the Next Level appeared side-by-side with the Sega Scream for a short while but eventually found its own niche as the slogan for the Sega CD. As the new add-on for the Genesis that was supposed to bring a whole new world of interactivity to gaming, it made sense to pair the two together. Some would argue that the advertising was more attractive than the product itself, but its effectiveness could not be denied. It is quite likely that the Sega CD would not have sold as well as it did (not a lot for a stand-alone console, but more than adequate for an add-on) had it not carried the advertising campaign. Unfortunately, for as much good as it did the Sega CD, not even the popularity of Sega’s marketing could save the Game Gear from a slow death, and nothing Bozell or Goodby did was ever enough to make the portable attractive to consumers. In a complete 180° turn from their feelings about the Genesis, gamers chose substance over style and ignored the fancy marketing in favor of the longer battery life and larger game library of Nintendo’s Game Boy.

These bumps in the road, major though they were, did little to deter Sega, which was engaged in an all-out media blitz to make its games fashionable and hip. It wasn’t necessarily about the quality of the gameplay (many people today question just how much better a game Sonic The Hedgehog really is than Super Mario World); it was about making people want the Genesis. This attitude, above all else, was what allowed Sega to claim more than 50% of the video game market by 1994, and the decision to deviate from it would be what would eventually cause it to lose it all when the Sony Playstation debuted in 1995.

These bumps in the road, major though they were, did little to deter Sega, which was engaged in an all-out media blitz to make its games fashionable and hip. It wasn’t necessarily about the quality of the gameplay (many people today question just how much better a game Sonic The Hedgehog really is than Super Mario World); it was about making people want the Genesis. This attitude, above all else, was what allowed Sega to claim more than 50% of the video game market by 1994, and the decision to deviate from it would be what would eventually cause it to lose it all when the Sony Playstation debuted in 1995.

No one but Sega knows why Goodby, Berlin, & Silverstein was dropped as its ad agency in 1996, ending what was not only the most successful marketing campaign in its history, but perhaps in the entire history of the industry. It has been suggested that Sega decided to change its philosophy completely with the Saturn, opting for a more passive and family-orientated approach in an attempt to give a fresh face to its new console. If this is true, it was the worst thing Sega could have done at the time, as it totally alienated the audience it had worked so hard for so many years to obtain. An attempt was made to revive the Sega Scream for the Dreamcast in 1999, but by then it was too late. Sega’s audience had long since left it. While things may not have turned out the way Sega had hoped, no one can deny the mastery of advertising that it wielded during the early ’90s that allowed it to dominate a market few people had thought it could even survive in. Maybe the lesson to be learned here is that in some cases, the clothes do make the man…or the company.

Sources

- Battelle, John & Johnstone, Bob. The Next Level: Sega’s Plans for World Domination. Wired Magazine. 1.06. December 1993.

- Czinkota, Michael, R. & Ronkainen, Illka, A. Sega: The Way the West was Won. International Marketing. 7th ed. 2004.

- Demovi, Marianna. Stanley Politt. Center for Interactive Advertising.

- Elliot, Stuart. The Media Business: Advertising – Addenda; Goodby, Berlin Wins Sega Business. New York Times. 3 July 1992.

- Foltz, Kim. The Media Business: Advertising – Addenda: Sega Commercials Take on Nintendo. New York Times. 31 August 1990.

- Horowitz, Ken. Interview with Micheal Katz. Sega-16. 28 April 2006.

- ————-. Interview with Al Nilsen. Sega-16. 8 March 2008.

- Kent, Steven L. The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. 1st ed. 2001.

- Lincoln, Howard. Interview with Game Zero Magazine. Game Zero Magazine. 9 August 1992.

- Pettus, Sam. Genesis: A New Beginning. SegaBase. 15 May 2000.

- —. Kamikaze Console: Saturn and the fall of Sega. SegaBase. 15 May 2000.

- Post, Karen. Brand Voice. Fast Company. 2004.

- Sheff, David. Game Over: Press Start to Continue. New York: Random House. 1993.

- Steel, John. Truth, Lies and Advertising: The Art of Account Planning. New York: John Wiley and Sons. 1998.

- Stephens, Mitchell. The New TV: Stop Making Sense It’s Fast, Hip and Illogical. Welcome to the Future. Washington Post. 25 April 1993.

- The Media Business: Advertising; Sega Account Goes to Bozell. New York Times. 2 May 1989.

- Wark, McKenzie. The Video Game As Emergent Media Form. Media Info Australia. February, 1994: 71.