The following interview excerpt was originally published in the August/September 2000 issue of the Japanese Dreamcast magazine. It was translated by the author as research material for multiple sections of the book The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. While the actual interview is much longer, this translated section includes information specific to Rikiya Nakagawa’s early days at Sega and his work on arcade titles.

The following interview excerpt was originally published in the August/September 2000 issue of the Japanese Dreamcast magazine. It was translated by the author as research material for multiple sections of the book The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. While the actual interview is much longer, this translated section includes information specific to Rikiya Nakagawa’s early days at Sega and his work on arcade titles.

As the head of Sega’s AM1 development team, Nakagawa produced hits like the House of the Dead series. His experience in arcade development stretches back much further than his tenure as chief of one of Sega’s premier in-house studio. From his earliest days, Nakagawa programmed some of Sega’s greatest arcade titles, including, Ninja Princess, Alien Syndrome, and Choplifter. In this interview, he talks about his early experiences at Sega.

Dreamcast Magazine: You were a huge baseball fan since your second year in elementary school. You joined a junior team and played it pretty much every day, including holidays. You were also a big fan of the baseball anime Yakyû no Hoshi. Was that still the case in high school?

Rikiya Nakagawa: No, by the time I entered high school I moved on from baseball. I wasn’t getting any thinner and I was told that high school baseball was pointless. I went to a metropolitan high school. I caught up on all the fooling around I didn’t do in school before (laughs). I skipped school, played some Mahjong.

Dreamcast Magazine: “Fooling around” meaning what?

Rikiya Nakagawa: At that time skipping school by itself was fooling around. Slipping out during lunch break, meeting up in the park, and going to Mahjong parlors. I remember skipping school to go play Space Invaders in a coffee shop. I even went to the big arcades in Ikebukuro just to play Space Invaders. During that time I also played Galaxian, Heiankyo Alien, and Sega’s Head On. I wasn’t as captured by Space Invaders as the rest of Japan was at that time; I was always looking for new games to play. It was still like that when I entered college. Space Invaders didn’t really shock me, as I had previously seen Atari’s tennis games as well as block-puzzle games at bowling alleys and the like. And when I moved from Space Invaders to Galaxian, I tried to enjoy it with a sense of “Oh, they’ve made quite a leap. That’s amazing.” Each time a new one came out they had figured out some new things. I found that really interesting.

Dreamcast Magazine: How was college?

Rikiya Nakagawa: To be honest, I bought an electric guitar my second year of high school (laughs). My friends had dragged me to some concert or another, and it was so loud my ears started to hurt (laughs). But it was really cool in a way. From that point on, I was always going to shows of foreign artists, and I bought an electric guitar. But I got bored of rock during high school and when I entered college, I was more into fusion and jazz. I kind of went backwards through music history (laughs). So, in college I was in the jazz club.

Dreamcast Magazine: How did you get in touch with Sega?

Rikiya Nakagawa: I studied electronic engineering at college. Computers were just beginning to enter society, and my classmates at uni were joining companies like NEC and Fujitsu. They were picking the best programmers. As for me, I was good in math and science but didn’t like subjects of the humanities like geography or history, so I joined the department of technology. At the time, our university was the only one to offer programming lessons. They were the first university to buy PC8001 machines and teach on them, so I thought I’d become a programmer, as there also were many jobs in that industry. However, joining a regular technology company didn’t seem that interesting, and since I had always liked video games, I tried to find a company in that field. When I asked at the career center I got two options: Namco or Sega. Namco had just released Pac-Man and I was told “It’s hard to get into Namco, so why not try this other one?” with that other one being Sega (laughs) . There wasn’t even an exam or anything. I just filled out a one-page form, went home and got a tentative offer later that day. That’s when I made my decision.

Dreamcast Magazine: What was Sega like at the time?

Rikiya Nakagawa: When I joined, they were scouting university graduates in huge numbers, so there were five to six new guys in software (programmers), hardware (planners), and design. When you joined, they trained you for about half a year. You learned about circuits, program architecture and things like that. It really felt like school, you were studying from morning to evening. It really helped me out a lot in the end.

Rikiya Nakagawa: When I joined, they were scouting university graduates in huge numbers, so there were five to six new guys in software (programmers), hardware (planners), and design. When you joined, they trained you for about half a year. You learned about circuits, program architecture and things like that. It really felt like school, you were studying from morning to evening. It really helped me out a lot in the end.

Dreamcast Magazine: One of the people joining the company with you was Yu Suzuki. What was he like?

Rikiya Nakagawa: Not much different than he is now (laughs), but during training he always asked questions, more enthusiastically than anyone else.

Dreamcast Magazine: Tell us about Sega’s hardware at the time.

Rikiya Nakagawa: When I joined, the Famicom had just been released. Sega had the SG1000 but wasn’t selling it anymore.

Dreamcast Magazine: Afterwards you’d work on several projects and would eventually be appointed head of AM1. Could you tell us about that?

Rikiya Nakagawa: Yu Suzuki was already moving independently at that point, working on things like Studio 128 and such. Our boss at the time, Yoji Ishii, was assigned to CS (consoles) and we had two R&D teams: AM2/CRI of which Yu Suzuki and I were a part of as well as [Hisao] Oguchi’s AM3 (now Hitmaker). That’s how the current form came about.

Dreamcast Magazine: What changed for you when you were appointed department head?

Rikiya Nakagawa: I didn’t have to code myself anymore (laughs). My job mainly revolved around production and managing schedules.

Dreamcast Magazine: What was the most memorable project you worked on in AM1?

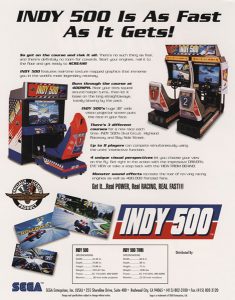

Rikiya Nakagawa: That would have to be Indy 500 (1995, Model 2). I think. Probably an unexpected choice. We had already used CG graphics in Wing War (1994, Model 1), but Indy 500 was the first time we were able to do proper color textures, and afterwards we had a really good handle on CG graphics. It was a huge deal. Only because of that could we then do Wave Runner and House of the Dead. Up until then, AM1 had only done games with 2D sprites, but from then on things completely changed.

Dreamcast Magazine: What would you say is the”image” of AM1? AM2 has been seen as “Yu Suzuki’s group of high-end hit-making honor students,” while AM3, like Oguchi, is known for its planning and design. Would you feel that the image of AM1 could be described as “steady” or “reliable?”

Rikiya Nakagawa: Simply put, I think it’s good that we didn’t have a set flavor, so to speak. We could basically do whatever we wanted, as long as it was fun. For example, doing kiddy ride attractions like Wakuwaku Anpanman is a bit… you know? But because we did it, we were able to learn how kids would react. So, recently we would tell mentally drained staff members to relax and play some Wakuwaku.

For the complete story of Nakagawa’s role in the development of many Sega arcade classics, be sure to read The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. The book chronicles Sega’s arcade legacy from 1966-2003 and is available in paperback and digital formats now from Amazon.

“He always asked questions, more enthusiastically than anyone else.” – In reference to Yu Suzuki. That stood out most of all in this interview! Thanks for posting the translation!