Creating a video game is no easy feat. Creating one that bears a license as famous as Jurassic Park is even harder, and the pressure involved in making a product that is both fun and original while remaining true to its source material is something that very few licensed games ever actually accomplish. With this thought in mind, developer BlueSky assembled a dozen highly creative minds to give the Genesis a great game. Though many today might be quick to point out the flaws in Jurassic Park, the amount of dedication and hard work that went into making it is something that needs to be recognized.

They studied dinosaurs, read voraciously on the subject, and took field trips to zoos and museums of Natural History. During the fifteen months that the BlueSky software team spent working on Jurassic Park, the members slowly evolved beyond their original capacities of artists, designers, programmers, and animators; and by the end of the project, they were all practically amateur paleontologists. BlueSky locked itself in its office building, a mere fifteen miles from the San Diego Zoo, and labored feverishly to bring Steven Spielberg’s cinematic masterpiece to life on the Sega Genesis.

Back to the Past

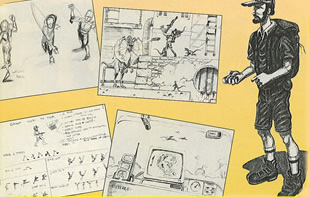

Sega acquired the Jurassic Park license shortly before the movie debuted and work quickly began on the game’s design. The first step was to create a script that would allow the player to follow many of the events of the film while offering something that went beyond it. Producer Jesse Taylor teamed up with art director Dana Christianson and artist Doug TenNapel (of Earthworm Jim fame) to brainstorm about the best possible way to recreate the Jurassic Park experience. After going over several different possibilities, the trio decided on a traditional side-scroller. To make their game different from the innumerable other side-scrollers glutting the Genesis, the team would have to give it something special, something that no other game could match.

Sega acquired the Jurassic Park license shortly before the movie debuted and work quickly began on the game’s design. The first step was to create a script that would allow the player to follow many of the events of the film while offering something that went beyond it. Producer Jesse Taylor teamed up with art director Dana Christianson and artist Doug TenNapel (of Earthworm Jim fame) to brainstorm about the best possible way to recreate the Jurassic Park experience. After going over several different possibilities, the trio decided on a traditional side-scroller. To make their game different from the innumerable other side-scrollers glutting the Genesis, the team would have to give it something special, something that no other game could match.

BlueSky programmers assembled a game engine that emphasized artificial intelligence. Not knowing how dinosaurs might actually behave in a given situation (their being extinct for sixty-five million years kind of made that hard to do), the team observed different animals, including birds and reptiles. Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park novel exploded into bookstores just as the theory of dinosaurs evolving into birds was beginning to gain steam in scientific circles, so the team took special care to reflect the latest science, and they observed the physical movements and feeding habits of birds and reptiles like ostriches and alligators. Their efforts led to the creation of Artificial Dinosaur Intelligence (ADI), which gives the dinosaurs multiple reactions to different situations. Some of the more common creatures, like the Triceratops, have three or four possible reactions. Throw a grenade at one, and it might bull rush you or just turn and run. There is really no way to know what the dinosaurs might do, so no two plays are ever the same.

The Velociraptors are especially smart, something that mimics their actions in the film. Unlike the other dinosaurs, they have up to a dozen possible reactions, depending on several factors like the stage being played and the character’s sophistication (weapons and equipment being used). Sometimes, a raptor might smell you, decide you’re not worth eating, and walk away. Other times, it might pounce on you mercilessly or even chase you across the stage! It might seem quite simplistic now, but the amount of care BlueSky gave to its ADI design was quite uncommon on consoles at the time, and it represented a significant leap in how designers addressed the problem of artificial intelligence in console games.

All the Effort of a Hollywood Blockbuster

No matter how believable the dinosaurs behaved, they wouldn’t be too convincing unless they looked the part. In this regard, BlueSky spared no expense, and nine of the twelve members involved were graphic artists and animators. Doug TenNapel was the lead artist, and his bunch went to great lengths to bring some of IL&M’s award-winning dinosaurs to the aging Genesis hardware. To create Dr. Alan Grant, team member Mark Dobratz was videotaped in front of a blue screen background. As he went through Grant’s repertoire of movements, certain frames of the tape were digitized and compressed. Graphic artists could then tweak his actions, adjusting the colors and enhancing his movements. The result was a fluid animation sequence for each of Grant’s moves. In all, over fifty different actions, such as walking, running, jumping, and climbing were digitized and put into the game.

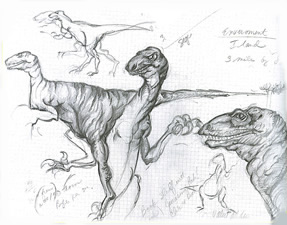

As complex a process as it was to make Dr. Grant seem real, it was even more difficult to make the raptors come to life. How do you accurately animate a creature that has been dead for millions of years? Well, you talk to the same experts who consulted on the film, for starters. Before the first dinosaur could be made, the animation team had to take into account each one’s shape, anatomy, and size. To this end, Sega brought in top paleontologist Dr. Robert Bakker (the chap who orients you on dino behavior in the Sega CD version of the game) to talk to the team about dinosaur anatomy. Dr. Bakker’s most important prop? One fresh supermarket chicken, which he dissected in front of his audience to show them the similarities between dinosaurs and birds. Interestingly enough, soft tissue recently discovered within the bone of a sixty-eight million year-old T-Rex has been confirmed to contain collagen (the main protein component of bone) similar to that found in the common chicken. Dr. Bakker was preaching this to the BlueSky developers more than a decade earlier! Later, stop-motion photography was used with models similar to the ones used in the movie, and this allowed the team to give each creature a full complement of life-like moves and actions. The raptors have the most animation – over twenty different movements, more than double the amount of the other dinosaurs, and can do everything from hiss and bite to sneak and stalk.

Once all the animation sequences were done, artists could take the data and enhance it in computer paint programs. Special smoothing and blending techniques were used to ensure consistency between the colors and the increments of movement. Once this was completed, the animations were ready to be integrated with the backgrounds, which were themselves quite large (some extend twenty or thirty screens). The backgrounds were created using a tiling technique that takes an image and breaks it down into smaller tiles, which then reform the original image when combined. By flipping them over and rotating them, the background artists can create larger backgrounds. The Genesis screen is composed of 320 x 224 pixels. Normally, a black and white image of this size would take up about 70k of cartridge space; however, tiling an image reduces this dramatically. For example, an image of 71, 680 pixels can be turned into 1,120 tiles (8×8 pixels each). By reducing the image to a hundred unique tiles, the amount of space it takes up can be reduced to 7k. This is one of the many compression techniques used to fit everything into Jurassic Park‘s sixteen megs.

Once all the animation sequences were done, artists could take the data and enhance it in computer paint programs. Special smoothing and blending techniques were used to ensure consistency between the colors and the increments of movement. Once this was completed, the animations were ready to be integrated with the backgrounds, which were themselves quite large (some extend twenty or thirty screens). The backgrounds were created using a tiling technique that takes an image and breaks it down into smaller tiles, which then reform the original image when combined. By flipping them over and rotating them, the background artists can create larger backgrounds. The Genesis screen is composed of 320 x 224 pixels. Normally, a black and white image of this size would take up about 70k of cartridge space; however, tiling an image reduces this dramatically. For example, an image of 71, 680 pixels can be turned into 1,120 tiles (8×8 pixels each). By reducing the image to a hundred unique tiles, the amount of space it takes up can be reduced to 7k. This is one of the many compression techniques used to fit everything into Jurassic Park‘s sixteen megs.

With the animation sequences and backgrounds complete, the team could then decide where to place the dinosaurs and other game elements throughout each stage. Both the producer and the game designers had to take great care at this part of the process, as where they placed these elements would determine the game’s balance and difficulty. Say that they decided to fill an intersection with a Velociraptor. They could choose from any one of the creature’s twenty animation sequences to determine how it would react when the player arrived at that specific point. It was not uncommon for the team to put up to six different animation sequences at a critical point, with each one depending on how the player acted. Another example would be placing a flock of procompsognathus (also known as “compys,” the tiny pack ravagers from The Lost World) on one side of a rock. If the player chose to take a higher path to avoid them, the designer could put a triceratops between two trees, forcing him to have to make a tricky jump over its horns. As the producer and designer decided the best places to put enemies and obstacles, a production assistant took notes, marking it all on map, or flow chart. The map was then given to the programmer, who implemented all the suggestions.

Recording Prehistoric Sounds

How things sound in Jurassic Park is just as important as how they look. Many of the sounds used come from different sound libraries created by such companies as LucasFilm and the BBC. Using pre-recorded sounds greatly decreased the amount of time and money (as well as travel) invested in acquiring all the sounds needed for the game; however, some sounds, specifically the roar of the T-Rex and other dinosaurs, don’t exist naturally and had to be recreated. Sega made ample use of those dino sounds created for the Jurassic Park film, and it even went so far as to create some of its own for the CD game. The Sega Multimedia Studio sent sound technician Brian Coburn to the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia for research. Coburn figured that the roar of a bull alligator would be about as close as you could get today to that of a T-Rex, so he set out to record it. Along the way, he also recorded sounds of several bird species. Back at his lab, Coburn modified each sound until he reached the desired effect. By lowering the bird songs several octaves (lowering their frequencies and increasing bass sounds), he was able to create distinctive roars for each dinosaur. Many of these sounds were eventually used in the cartridge version of Jurassic Park, as well as the two sequels. Together with composer Sam Powell’s score, they did much to create the ambience of Isla Nublar.

Dinosaurs Walk the Earth

Once all the animations, backgrounds, and audio effects were completed, the game was sent for testing. Testers spent hundreds of hours over the course of several weeks searching for bugs. The result is the game that was a major hit for Sega (we reviewed it in February of 2005), spawning two more sequels as well as an interesting CD version. An entire franchise was born, and even the Saturn and Game Gear partook in the Jurassic goodness (other systems saw Jurassic Park games, but none sported the entire line).

The Genesis game is not perfect, and few games ever are, and some would be quick to say that its biggest flaw stems from the angle from which it was designed. Virtually two thirds of the development team focused on the graphics and animation, and this most likely affected the gameplay. Gamers have been complaining about everything from level design to the difficulty for years, and I’m sure that more than a few now look at the development and say “aha! I knew it!” This seems unfair to me, once you consider the extra effort put into the animation and to make the artificial intelligence as strong as possible. That’s not even mentioning the added ability to play as the raptor, something decidedly different from the standard of the day. It’s impossible to please everyone, but I think that BlueSky did more than its part to make happy as broad an audience as possible. Like it or love it, there’s no denying the significance of this release or the place it holds in Genesis history.

The Genesis game is not perfect, and few games ever are, and some would be quick to say that its biggest flaw stems from the angle from which it was designed. Virtually two thirds of the development team focused on the graphics and animation, and this most likely affected the gameplay. Gamers have been complaining about everything from level design to the difficulty for years, and I’m sure that more than a few now look at the development and say “aha! I knew it!” This seems unfair to me, once you consider the extra effort put into the animation and to make the artificial intelligence as strong as possible. That’s not even mentioning the added ability to play as the raptor, something decidedly different from the standard of the day. It’s impossible to please everyone, but I think that BlueSky did more than its part to make happy as broad an audience as possible. Like it or love it, there’s no denying the significance of this release or the place it holds in Genesis history.

Sources

- Behind the Scenes: The Lost World. Lost World.com.

- Lavroff, Nicholas. Behind the Scenes at Sega: The Making of a Video Game. Prima Publishing. 1994.

- Norris, Scott. Dinosaur Soft Tissue Sequenced; Similar to Chicken Proteins. Nat. Geo. News. April 12, 2007.

- The Making of Jurassic Park. Sega Visions Magazine. June/July 1993.

Pingback: Retrovolve – Jurassic Park for Sega Genesis Was a Worthy Movie Tie-In

Pingback: Jogos Licensiados | Drive Your Mega