Nothing in the gaming industry is harder than launching new hardware. Every console goes through so much on its journey from the design board to retail shelves, that many of those responsible feel like proud parents. It takes great experience and knowledge to do this, and only  a few select people possess both. Ken Balthaser is one such person. As Sega’s head of product development, he saw the Genesis launch and bore witness to the gaming revolution it set in motion.

a few select people possess both. Ken Balthaser is one such person. As Sega’s head of product development, he saw the Genesis launch and bore witness to the gaming revolution it set in motion.

Balthaser was well prepared for the task at hand, having plenty of experience in the industry from his early days at Atari and Epyx. Hired by Michael Katz in 1989, he played a major role in some of Sega’s biggest and most talked about titles. Eventually moving on to such companies as Electronic Arts, Balthaser now runs his own web design company, Balthaser Online.

Sega-16 recently had a chance to chat with Mr. Balthaser by phone, and he had some interesting stories to tell!

Sega-16: Thanks for joining us. What exactly, was your role at Sega?

Ken Balthaser: My position there was Head of Product Development, and I joined them in… I believe it was 1989, before they launched. It was a really a very small company, located in south San Francisco. They were going to launch the Sega Genesis, and things were just crazy.

Sega-16: The pressure must have been overwhelming, considering the stakes.

Ken Balthaser: It was crazy, as always happens in these things, because everybody is, you know, just frantic to get everything done in time. Plus, we were growing so fast, and you run out of space quickly when you’re hiring people that fast. It was just a fast paced, hectic environment. We were growing, and Sega had its work cut out for it against Nintendo, so… we were all crammed together in one building. I remember when I was hired on, they didn’t have any office space, so I had to share a cubicle in the back of the building with uh..I think it was a human resources person, right in the back with customer support.

It was kind of crazy, so yeah, things grew very quickly after that. They hired me to create the U.S. development arm for the Sega Genesis. Everything was being done in Japan prior to that, and they felt that if we were going to have any success in the U.S., they had to have some U.S. development and they had to design some games for the U.S. market. So, that was their interest in building a product development arm. They hired me because of my background at Atari and at Exidy, so I came in as head of development.

From the very beginning, my whole plan was not to do in-house development, which required lots of time for hiring and staffing. When a project development arm grows that large that quickly, you spend all your time managing that rather than developing games, so I opted to not do in-house development but rather go outside. So instead of hiring programmers and designers, I hired therefore, people to support that vision. I hired producers, using contacts of game developers — people I had known back from my days at Atari — and we brought them under contract to manage those who were developing games for us, so that’s how we did it. We had a very good group of producers, and we had development going on all over the place, in Hungary, England, France, and a bunch of other places. That’s how we began development here, and I think very quickly we were able to get our first products out the door.

Interestingly enough, the company, prior to my coming aboard, had signed up some licenses. One of the licenses was M-1 Abrams Battle Tank. Sega needed the game for the Genesis and signed it. Unknowingly, they signed up this 3D game, and the Genesis was not particularly good at doing very complex polygons. You know, most of its stuff was character-based. Anyway, we hired a group in England that had a great deal of experience doing this sort of thing, and so the first U.S. game was Abrams Battle Tank.

Sega-16: We’ve recently reviewed M-1 Abrams. It’s a pretty solid title, even though it hasn’t aged too well.

Ken Balthaser: It’s amazing. I look back on it and think, “What were we thinking?” I mean, to do real-time 3D on a video game system at the time was very hard, but these guys were very smart, and they made it work, and the very first game to make it out of the U.S. was that game. So, that was essentially the beginning.

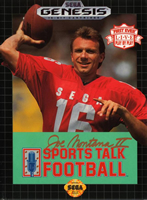

Sega-16: Going back to what you said about the licensing, sports were given great importance at Sega, as highlighted by the company’s signing of big name icons like Joe Montana and Tommy Lasorda. Was there ever any special pressure to outdo the competition, to define the Genesis as the console of choice for sports games, or did things just happen to work out that way on their own?

Ken Balthaser: No, it was particularly set out to do, because we knew that sports would always be popular. People – gamers – like action, and they like sports games. Electronic Arts had been successful, though these were still the early days. They had been successful with their sports franchises on the PC, and we knew we could develop sports games of our own. EA was always a step ahead of us, and what we did with Joe Montana Sports Talk Football to make it different was to do the play-by-play. That had never been done before. (Click on the box art at left to hear a sample!)

Ken Balthaser: No, it was particularly set out to do, because we knew that sports would always be popular. People – gamers – like action, and they like sports games. Electronic Arts had been successful, though these were still the early days. They had been successful with their sports franchises on the PC, and we knew we could develop sports games of our own. EA was always a step ahead of us, and what we did with Joe Montana Sports Talk Football to make it different was to do the play-by-play. That had never been done before. (Click on the box art at left to hear a sample!)

Sega-16: We recently spoke to producer Jim Huether about that game, and how revolutionary it was.

Ken Balthaser: Yeah, it was very unique, and we knew we had to do something, because we couldn’t just go head-on with John Madden. Joe Montana was a great license and made a lot of money for us, because he was, you know, the player at the time, but John Madden Football…that franchise had begun and it was going to be hard to overtake it. We needed something to differentiate Joe Montana, and that was the “sports talk” feature. As a matter of fact, Trip Hawkins (founder & president of EA at the time), at a conference sometime later on cited that game as true multi-media. That made me feel good, you know. Here’s Trip Hawkins, president of EA saying that in his mind, it was the first true multi-media video game.

So, that was really unique. I mean, it was risky; no one had ever done that before. The programmers down in L.A. had developed some table top games and used this technology to do very minimalistic play-by-play, and they hired someone to record these clips, which they put on a little chip that could play back. The trick was to get that into a video game cartridge and do all the tricks to integrate it all. At the end of the day, I’m very proud of that game. It’s an achievement, and I’m very proud of the fact that we were able to build a very fine organization very quickly and get the game out, because it was hard. Sega had some great developers making wonderful games.

Sega-16: What did Sega of Japan think about this strategy of signing big names?

Ken Balthaser: They were not particularly in favor of it, because they don’t do that in Japan. Licensing is not a big thing, and to a great extent they’re correct. The main thing is the gameplay. In the U.S., it’s different. Licenses are big and have lots of appeal, but you need a great game to go along with it. You can’t have a license wrapped around a crappy game and expect it to sell, because the player sees the crap right through the big name. But as for Japan, yeah, they were quite shocked, actually.

Some of the licenses were more successful than others. I remember one of them that we did; it turned out to be an embarrassment. We couldn’t get Mike Tyson, the boxing heavyweight champion of the world at the time. We couldn’t get Tyson, because that license was tied up. Later, Buster Douglas became champ, and we went out like, “We have to have him,” and signed Buster Douglas, of course, hoping that he would successfully defend the title. [Laughs] It ended up lasting like a few days, because he lost the title in his very next bout! We had licensed Buster, had a big promotion about Buster Douglas, produced a boxing game around him. Then he had his next fight, and I remember we rented a hotel to see him that night, kind of a conference room. It had a big screen TV set up, and everyone was gathered around in chairs to watch Buster Douglas fight, and right before our very eyes he lost his title, and he never won again!

We also did Disney licenses. That is, we had a contract with Disney. A game that we did for them…one of the very first games we did was Fantasia. That game nearly cost us dearly; there was so much pressure on me and on the team, that unfortunately I made the call to release it even though the gameplay wasn’t ready. I truly wish I hadn’t, but sometimes you have to make those decisions. You need games in the pipeline, especially big licenses, but the game was just simply unplayable.

Sega-16: I remember that I sent away for that game, being the huge Mickey Mouse fan that I am. Imagine my surprise when I played it! The graphics were just gorgeous, but the gameplay was horrible.

Ken Balthaser: Yeah, the graphics were wonderful, and they really caught the mood. They did some really cool things with parallax scrolling in there, but again… hindsight’s 20/20. I wish now that I would’ve just said no and sent it back for another two months or so, to tweak the gameplay. I think it could have been a really fantastic game if we had done that.

Another thing you need to know about that is that apparently Roy Disney did not know that Disney had licensed Fantasia to us, so apparently he did not know that we were making a game about it. He was quite upset about that. I don’t know the outcome, but I think there was a big stink over at Disney about it, and we may have even pulled production of the game, stopped selling it, because of it all.

Sega-16: Let’s go back to your work on sports games for a second. You were involved with several sports games on the Genesis/Sega CD, and many people are quick to think that the CD technology instantly offered much greater avenues for creativity. How much more freedom, if any, did the Sega CD afford you?

Ken Balthaser: I tried to explain that to Sega at the time, but they had this vision of, “Oh boy, now we have this CD; everything’s going to be different.” My point to them was that the big problem was the pipeline. You have this great and massive storage device, and you’ve got a system that can run graphics very quickly, etc., but you’ve got this little straw — I tried to characterize the inefficiency to the other executives, to try and show them what the problem was. Try to imagine that you have this great big oil tanker sitting off the coast with all this oil in it. You want to bring it ashore (the oil), but all you have is a garden hose. And basically, that’s the analogy. You had this storage device, this tanker, with a huge capacity for storage, but you just can’t get it off the tanker fast enough because of the little garden hose. And that was the whole problem with the Sega CD. Yeah, you could store all that data, but you couldn’t get it off fast enough at times, to do what you wanted to do.

But I mean… it could do… that is, it did add some nice visual things, some cinematic things. Games could store a hell of a lot of data. You just had to remember to design the software so that it could, you know, load data in the background. So it did offer an opportunity, but the expectations were a lot higher than they should have been for a new system like that. They just thought there was going to be this massive transformation. You know, because after all, the Genesis was the Genesis… the hardware’s the hardware…it does what it does. This massive storage device is good for audio and video, stuff like that, but it’s not going to change things overnight.

But I mean… it could do… that is, it did add some nice visual things, some cinematic things. Games could store a hell of a lot of data. You just had to remember to design the software so that it could, you know, load data in the background. So it did offer an opportunity, but the expectations were a lot higher than they should have been for a new system like that. They just thought there was going to be this massive transformation. You know, because after all, the Genesis was the Genesis… the hardware’s the hardware…it does what it does. This massive storage device is good for audio and video, stuff like that, but it’s not going to change things overnight.

Sega-16: How difficult was it to make a football game using mostly full-motion video? NLF’s Greatest is a decidedly different approach to the sport. What new challenges did it pose? Was it an attempt to do something different for variety’s sake, or was it designed to show off the capabilities of the system?

Ken Balthaser: It was both of those things. You always want to show off the capabilities of the system and prove it’s better than the competition, and you’re always looking to show new things. Sometime in the ’80s, I forget exactly when it was, Bob Jacobs of Cinemaware changed the way sports were done on the PC back then. They had a football game, TV Sports Football, and we wanted to do something like that.

Sega-16: After years of being at the forefront of sports gaming, Sega has apparently taken a back seat, selling off Visual Concepts to Take Two Interactive. Do you think Sega’s time as a leader in the genre has finally passed?

Ken Balthaser: I don’t know. I mean, Sega’s an entirely different company than it was when I was there. I’ve been kind of out of the loop as to what they’re doing now.

Sega-16 would like to thank Mr. Balthaser for taking the time to speak to us.

Pingback: Constante como las olas - GameReport